Key takeaways

- Benefit payments can help or hinder a pension’s plan funded status.

- Overfunded plans gain from “benefit payment lift,” which increases their funded status. Today, roughly half of all plans are overfunded.

- As funded status rises, the idea of plan hibernation may become more attractive, enabling strategic use of pension surplus.

I recently visited the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum with my 11-year-old son, where we saw the original plane flown by the Wright brothers in 1903. The plane was larger than I expected, and the first flight was shorter than I thought, but somehow, they managed to crack the code on how to make a machine fly. They did this by overcoming significant opposing forces.

A plane trying to take off has two main obstacles to overcome: weight and drag. Weight is forced by gravity and drag by air resistance. Planes overcome these factors with thrust and lift. Thrust comes from powerful engines and lift from the wings.

Ironically, both drag and lift are caused by air, which can either resist a plane’s motion or help it rise. Pension plans also face forces that either hold them back or propel them forward: obligations, contributions and investment returns.

The weight of obligations

The weight of a pension plan is the future obligation to pay benefit payments. It weighs less when rates are higher (as they were in 2022) but more when they are lower (protected by LDI strategies). Thrust comes from contributions and investment returns. A larger engine is like a more generous funding policy or aggressive asset allocation. Drag and lift also have their analogs, both arising from the payment of benefits. Most recently, more plans are experiencing the lift.

When payments hold you back

Underfunded pension plans face a significant challenge to becoming fully funded, simply because they are always paying out benefit payments. Pension risk transfer can magnify this problem. What we refer to as “benefit payment drag” comes from paying out a higher portion of assets than liabilities. Benefit payments are paid out at a 100% level whether the plan is fully funded or not. This means when an underfunded plan pays benefits, its funded status decreases.

Let’s take a simple example. A plan has $400 million in assets and $500 million in liabilities, or an 80% funded status. Now, what if it pays out $100 million in benefit payments? The plan is left with $300 million in assets and $400 million in liabilities. Its funded status percentage drops by 5% and is now 75% funded. That’s benefit payment drag, and it requires added “thrust” (i.e., returns or contributions) to overcome. The low funded status causes effective returns to be throttled down.

This illustrates one of the reasons it took so long for corporate pension plans to become fully funded again after the Global Financial Crisis. Plans typically pay out 5-10% of their plan assets each year in benefit payments, meaning the worse funded the plan is, the greater the impact of benefit payment drag.

For instance, an 80% funded plan paying out 7% of assets annually requires an additional 1.5% in return each year just to tread water (or pay the equivalent in contributions). That increases to 1.8% for a 75% funded plan. In short, the more underfunded you are, the harder it is to escape the cycle.

When payments push you forward

Now that about half of pension plans are overfunded, many plan sponsors are finding it relatively easy to maintain and improve their pension surpluses, due to “benefit payment lift.”

Let’s consider the same example as before but with a well-funded plan. The plan has $600 million in assets and $500 million in liabilities, or a funded status of120%. If it pays out $100 million in benefit payments, it’s left with $500 million in assets and $400 million liabilities—or a funded status of 125%, which is a 5% increase. This is equivalent to having an additional 1.5% in return just by letting the plan run its course. That’s benefit payment lift—and it means well-funded plans can improve their position simply by letting benefit payments work in their favor.

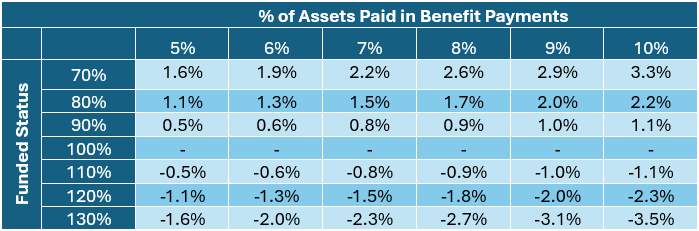

As the chart shows, there are a range of impacts on additional return needed (or underperformance that could be tolerated) for various levels of funded status and percentage of assets paid in benefit payments to maintain the current funded status.

Additional return needed due to the payment of benefit payments

In short, the higher the funded status, the more benefit payments work as a tailwind rather than a drag.

Considering the value of pension surplus

Where does this leave plan sponsors with overfunded plans? While plan termination is an option, plan hibernation can appear even more compelling if funded status is increasing. This opens the door to discussions on using plan surplus, which can lead to changes in asset allocation for overfunded plans. The overfunded plan has an additional buffer to perhaps take on a riskier portfolio to generate additional return.

Rather than a simple asset allocation at the end of the glidepath currently favored by many, newer investment strategies like LDI diversifiers that offer additional return can be more compelling. This excess return potential becomes more valuable if current proposals to use excess pension assets in defined contribution plans come to fruition.

Looking ahead

As sponsors shift from survival to optimization, recognizing the dual role of benefit payments—drag and lift—will be key. Those who harness the lift of surplus can better align their portfolios with both participant security and long-term corporate goals.