Executive summary:

- Market concentration today is the highest it has been in the last 29 years

- This has created an unprecedented headwind for active managers in the post-COVID era

- Historical relationships suggest if market concentration recedes or even just plateaus, a more conducive environment for active managers is likely

- There is no normal level of market concentration, but an active multi-manager structure can help navigate highly concentrated markets while also benefitting from any potential unwind

As markets grapple with the implications of artificial intelligence, the AI frenzy has meant that the six largest companies accounted for more than half of the U.S. market’s return in 2023 and year-to-date (August 2024) they have accounted for nearly half again.

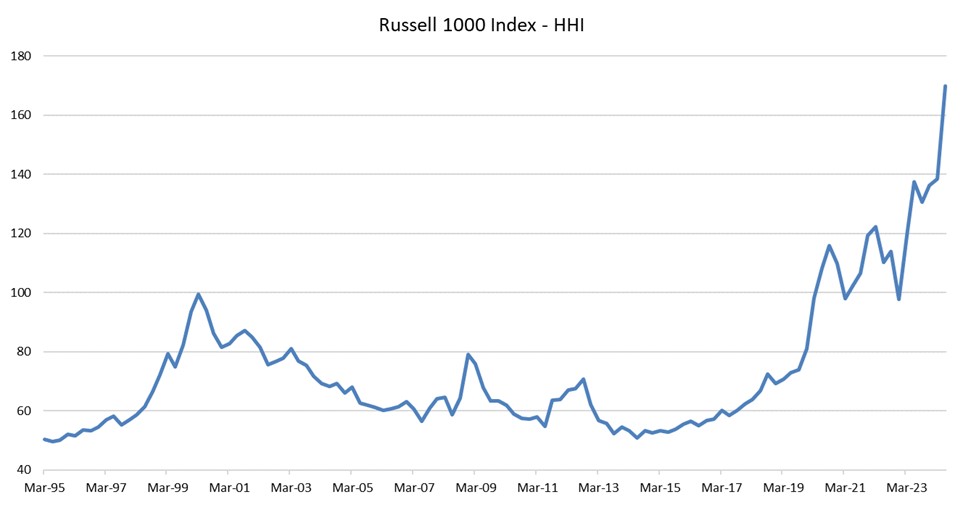

The concentration picture, however, is a trend that has been bubbling for several years. Using the Herfindahl Hirschman Index (HHI), a measure of index concentration, we can put into context how the U.S. market structure has evolved.

Looking at the Russell 1000 Index back to 1995, the HHI today is materially higher than it has been at any time during the last 29 years, including the dot-com bubble in 2000. An equivalent pattern exists in a global context given the weight of the U.S. in the global index.

What’s behind the rise in market concentration?

There have been two key events that have fueled the rapid increase in concentration since 2020. Following the onset of the COVID environment, ‘work-from-home’ winners (which included the mega cap tech-focused companies) accelerated their market share gains over traditional businesses. In 2023, the same mega cap names were key beneficiaries again, this time from generative AI. The release of ChatGPT captured the world’s imagination and we have since seen a flurry of investment in GenAI and the transformative impacts it may have.

For investors, this increase in concentration is something worth focusing on as it presents additional challenges to consider. The lack of diversification and breadth can reduce the stability of portfolio outcomes, particularly in passive strategies which may traditionally be considered well diversified. This was discussed in our previous article on the perils of passive investing. In fact, at the end of August 2024, over a quarter of a Russell 1000 Index passive portfolio and over 20% of a MSCI World Index passive portfolio was allocated to just six companies.

What influence does market concentration have on active managers?

Concentrated markets are structurally challenging for investors looking to build robust portfolio solutions. There have been few periods where economic fundamentals were dominated by such a narrow group of leaders, and it is widely accepted that effective diversification helps reinforce long-term outcomes.

Based on quarterly data from Russell Investments’ global manager universe (starting in September 2001), we compared the median 3-year excess return of global managers to changes in concentration over the same period.

The scatter plot demonstrates a clear relationship between the scale of active manager excess returns and the direction/size of movement in concentration. Entering periods of increasing concentration, active managers typically underperform (low left quadrant). Conversely, the strongest active returns have typically been achieved when this reverses and concentration is falling (top right quadrant of the chart).

It’s worth noting that all of the data points where we capture an increased change in HHI (concentration) above 10 (bottom most left of chart) have occurred during the last four years. This highlights the extreme nature of the headwinds active managers have been facing recently. However, history would suggest when concentration stops increasing or even declines, we could see a rebound in global active manager returns.

One other observation we can note is that the relationship between active manager returns and concentration is asymmetrically appealing. The outperformance of active managers in a declining concentration environment appears to be greater than the underperformance seen for equivalent increases in concentration.

Is there a reason for this relationship to exist?

Active managers typically exhibit a slight bias toward small-mid (SMID) cap stocks. They can explore the full universe of companies within their investable market and aren’t bound to weight the positions on their market cap like the index. For market concentration to fall, we must imply that the rest of the market is doing better than the largest companies. Hence the SMID cap bias of managers becomes a tailwind.

However, this isn’t to say that the link with market concentration changes is simply an indirect correlation with size. Greater cross-sectional volatility and lower correlations are also advantageous to active managers. The greater dispersion in stock returns increases the opportunities for skilled managers to pick out undervalued stocks, but as concentration has continued to move higher, we have seen cross correlations concurrently increase as greater parts of the market move in tandem.

Can we expect concentration to reverse?

Although concentration has reached historically high levels, it is not entirely without fundamental backing (unlike much of the dot-com period). Today’s mega caps have grown their earnings faster than the rest of the market and as such, comprise a larger proportion of the earnings generated by publicly listed entities.

However, in the U.S., we can see that the concentration of the market capitalizations has increased at a faster rate than their fundamentals, indicating some of the more recent concentration changes have been driven by more expensive valuations. This could be an indication of even larger relative growth expectations for the top 10 index names, but it would suggest that these expectations are already priced in.

Additionally, while there is no normal level of concentration that equity indices should tend toward, market valuations are grounded in fundamentals. This means that there are economic reasons why, in the long term, companies will struggle to sustainably defend concentrated economic profits and market capitalizations. For instance:

- When companies are making outsized profits beyond the cost of capital, basic economics suggests more companies will enter the market to take advantage, thereby increasing competition and supply. Barriers to entry will dictate how quickly or far that could normalize.

- When companies become too large, it can increase the scrutiny on them from regulators, given their economic importance and potential anti-competitive behavior. It may also be harder to acquire competitors, which has been a tactic of choice recently.

How can an active multi-manager solution help performance outcomes in this market?

It is difficult and arguably dangerous to try and specify how much of the AI story driving concentration is priced in. There remains a high level of uncertainty on the opportunities to monetize the technology, the pace of adoption, and the ultimate winners/losers.

Multi-manager solutions help improve consistency of outcomes by deploying a line-up of discerning and critical investors that use different investment processes. This spreads the decision risks on which and how much weight of any one company a portfolio should own. This can help navigate themes like the AI developments currently being experienced, without becoming too exposed to individual stock-specific risks.

It's no secret that active managers have faced unprecedented headwinds in recent years. We believe that a best-practices approach to overcoming these challenges is to utilize a mix of active managers, as this affords investors multiple levers to try and manage the risks and outcomes in these tougher periods. At the same time, such an approach also means investors are poised to benefit from any active returns in a more balanced market as well as additional tailwinds during an unwind of concentration.