A lesson in the perils of abandoning your investment plan

Highway driving is often a tale of two stories. The preferred narrative is one void of red brake lights and comfortably cruising to the sound of your favorite playlist. The less preferred being the traffic jam that seemingly goes on forever while you frustratingly ponder why flying cars have not yet caught on. After inching along for a while, you question if you should take the next exit in hopes of finding an alternate route to your destination.

I have, and inevitably it’s been a mistake. Often, I end up driving through small towns full of traffic lights and rambling detours before I can get back on the highway. Without fail, I rejoin the highway only to find the traffic jam had eased up some ways back. Annoyingly, I’ve found that when I’ve patiently waited on my original route, cranked up my playlist or favorite podcast, the traffic jam has cleared sooner than I had expected, and I’ve accelerated back to my ideal cruising speed.

Investing can be a lot like that. Let’s take the start of 2022 as an example. After cruising at comfortable speeds in 2021, reaching new highs (or record-setting arrival times), the start of the new year brought us a traffic jam that briefly sparked similar emotions to those felt in March 2020.

Looking through the rear-view mirror at the last traffic jam for inspiration, we are reminded that almost no one was left untouched by the coronavirus outbreak, or the lockdown imposed to attempt to contain it in the Spring of 2020. Most of us were tasked with making sudden difficult decisions that impacted family, health, and finances. For many investors whose portfolios are needed to finance their retirement or other financial goals, taking the first exit – inevitably, that meant moving to cash1– was their first response.

As markets plunged in early 2020, the only certainty was that uncertainty reigned and emotions ran high as we consumed headlines that painted an extremely draconian future for the world economy. Advisors were quick to transition to a remote setting, only to be welcomed by a deluge of panic-stricken phone calls and e-mails questioning if it was the right time to fully liquidate investment portfolios, sever losses and batten down the hatches on any money left over. But were investors well-served by abandoning their long-term allocations to move to the safety of cash? In other words, is getting off the highway a good idea?

The story of moving to cash

Ensuring one’s head can meet the pillow at night, with peace and tranquility, is unquantifiable in dollars or percentages. If investors did choose this path, now may be the time to gently remind them that others have done the same in the past. Parting ways with equity investments at or near a market bottom isn’t a new trend. During times of crisis, many investors start thinking about what happened during past recessions, such as the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 and 2009. Memories of these prior events, coupled with the barrage of frightening headlines, can make it tough to maintain a planned asset mix and stay invested amid a market correction.

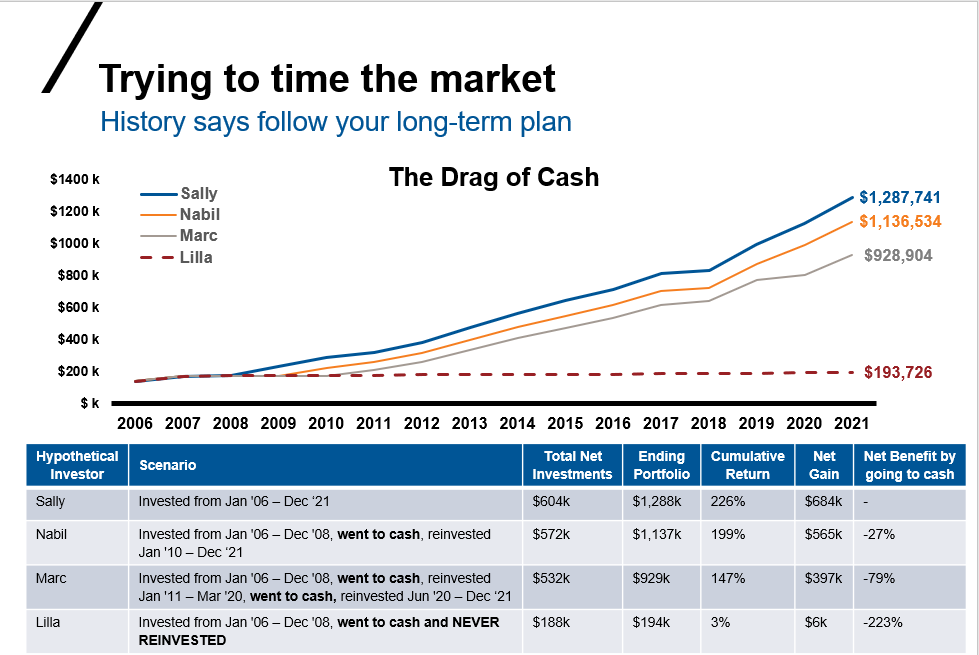

In the spirit of better preparing the playbook for the next crisis, we have looked at four hypothetical Canadian investors and their slightly different paths through two major crises. Each investor started with $100,000 CAD in a balanced portfolio on January 1, 2006. The 60% equities / 40% fixed income balanced portfolio consists of 20% Canadian equities (represented by the S&P/TSX Composite Index), 20% U.S. equities (represented by S&P 500 Index), 20% international equities (represented by the MSCI EAFE Index) and 40% Canadian fixed income (represented by the FTSE Canada Universe Bond Index).

- Sally (stays on the highway - invested through thick and thin)

- She also invests $8,000 per quarter until the end of December 2021. Over this 16- year period, Sally’s net investment was $604,000 and by the end of the last month, her portfolio was worth more than $1.28 million. Despite going through both the GFC and the COVID–19 crisis, Sally’s portfolio had a cumulative return of 226%.

- Nabil (got off the highway during the Global Financial Crisis but stays invested during the COVID–19 crisis)

- Invests $8,000 each quarter as well, although Nabil moves to cash at the end of December 2008 when his portfolio is worth $174,000 at that time. Even though Nabil lost principal, he managed to bail before the bottom of the GFC which occurred on March 9, 2009.

- On Jan. 1, 2010, when the GFC rebound was seven months old, Nabil comfortably re–enters the market and moves his cash back into a balanced portfolio. Nabil also resumes $8,000 dollar -cost averaging each quarter.

- By the end of December 2021, Nabil’s portfolio is now worth roughly $1.14 million or roughly $151,000 less than Sally’s.

- Marc (got off the highway by trying to time the market … and stumbles through his detour)

- Has a similar strategy to Nabil, although he waits an extra year before re–entering the market in early 2011. Then, after being invested for more than nine years, he moves back into cash at the end of March 2020, days after the COVID–19 market bottom on March 23 when the S&P/TSX Composite Index closed at 11,228.49. At the end of May 2020, Marc has some serious fear of missing out after seeing a 14% return from Canadian and U.S. equities and 4% in bonds and decides to re-enter his balanced portfolio. If you thought missing out on the positive returns was bad, 11 days after the point of re-entry, Marc was greeted with an 831–point drop from the S&P 500.

- By the end of December 2021, Marc’s account would be worth $929,000, about $359,000 less than Sally’s account and $208,000 less than Nabil's.

- Lilla (got off the highway at the very first sign of a traffic jam – the GFC-- and never got back on. She stays in cash for the whole trip)

- This scenario could be considered the worst case, where Lilla used the same investment scheme as Nabil. However, after leaving the market in 2009, she was never comfortable resuming her previous investment strategy. Lilla’s portfolio has gained 3%, and was worth $194,000 at the end of December 2021, or approximately $6,000 more than the total invested.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Morningstar. Rebalanced monthly. Net Benefit by going to cash: cumulative return of Nabil, Marc, or Lilla minus cumulative return of Sally. Balanced Portfolio: 20% S&P/TSX Composite Index, 20% S&P 500 Index, 20% MSCI EAFE Index, 40% FTSE Canada Universe Bond Index. Cash: FTSE Canada 91 Day T-Bill Index.

2These scenarios are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute any investment advice. Indexes and/or benchmarks are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly.

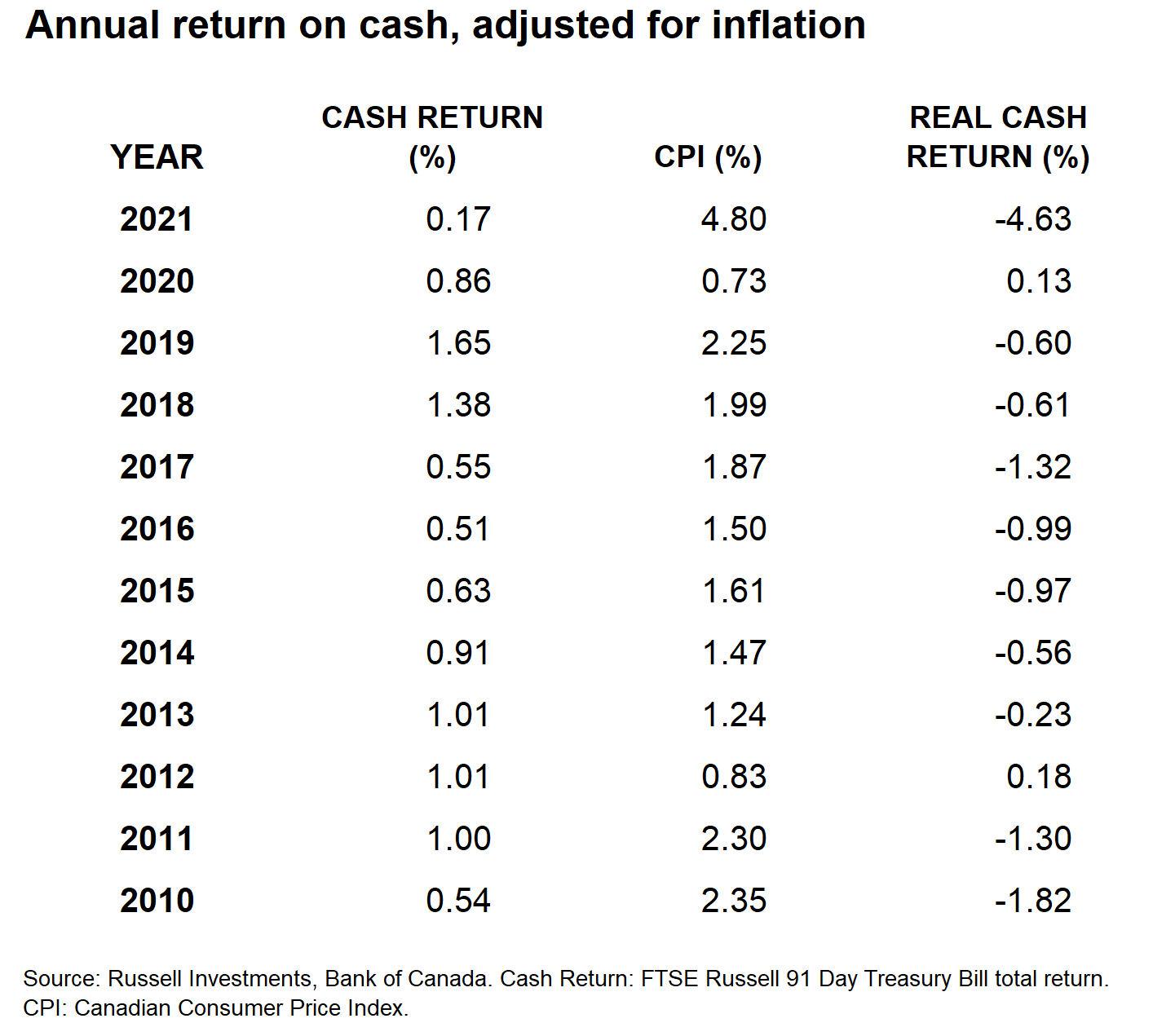

Investing in cash has a cost

For many, cash equals certainty. And once that certainty emotion is fulfilled, difficult decisions follow. Clients may wish they raised more cash if markets decline further or suggest they wait for the next pullback to reallocate to their asset mix. This time in limbo has a cost associated to it – the capital eroding impact of inflation. Unmistakably, investors who have over relied on cash while pondering their investments for the last 10 years have paid for it dearly. The table below highlights the low returns on cash for the last decade followed by real returns once inflation is accounted for. There are likely no financial plan projections that can be fulfilled when cash returned negative real rates in 10 of the last 12 years.

Click image to enlarge

The bottom line

Market cycles come and go, and without fail, investors will find themselves in similar decision-making situations. The flight to cash will be tempting and we encourage advisors to draw on the highway traffic example to instill trust in following the plan in those instances. Modern vehicles are equipped with advanced safety features to ensure traffic is navigated with comfort and peace of mind – much like a properly diversified portfolio. Replacing the short-term traffic report with your preferred soundtrack while we wait with patience will likely keep the stress at bay.

If you have a long–term time horizon and an investment plan in place, but clients still find themselves tempted to stray from that plan amid the crisis, it may make sense to revisit the asset mix to ensure an adequate allocation to quality fixed income and alternative investments that can help insulate wealth from the effects of declining markets.

2022 has just begun. Markets (in fits and starts) have broadly recovered, herculean global vaccine distribution efforts look promising, and we are optimistic the future is bright. Despite this positive backdrop, we are only a few headlines away from knee jerk financial reactions that can have catastrophic consequences on long-term wealth creation. If long-term investors stay invested and dialed in on their long-term objectives, the data suggests they are better for it. As Tom Cochrane and Rascall Flatts both acutely pointed out, “Life is a Highway” and perhaps they simply forgot to mention that there will be traffic from time-to-time.

1Cash refers to any short-term investment that provides a return in the form of an interest payment. This includes bank accounts, money market investments, Guaranteed Investment Certificates and other short-term fixed income instruments.

2Canadian equities represented by S&P/TSX Composite Index, U.S. equities represented by S&P 500 Index, international equities represented by MSCI EAFE Index, Canadian fixed income represented by FTSE Canada Universe Bond Index.