Risk from Chinese debt? We think it’s overblown

Are worries over China’s high level of debt warranted?

Besides focusing on the latest headlines surrounding China-U.S. trade relations, markets are also becoming increasingly concerned about the risks that China’s high level of debt poses to the global economy. After all, 2019 saw a number of defaults among Chinese banks, including Baoshang Bank and Tewoo (a large commodities broker).

As the worries mount, it’s worth addressing whether these concerns are truly warranted, or overblown to an extent. Let’s dive right in and tackle this, as well as look at how much of a handbrake such a high level of debt may have on Chinese growth.

Chinese debt 101

Let’s start with the basics. The Chinese economy has a total debt-to-GDP ratio above 300%.1 Within this pile of debt, a substantial amount is comprised of corporate debt, which includes state-owned enterprises. There’s also a lot of off-balance-sheet debt, otherwise known as shadow debt, which the Chinese government has been cracking down on over the last three years.

To be clear, there are good reasons to be concerned about these levels of debt, especially given the increasing numbers of defaults. However, as always, the devil is in the details. Take Baoshang Bank, for example, where the Chinese government announced that creditors would have to take a loss. While this is technically true, 99.98% of investors were made whole.2

China’s bond market: Can active management provide value?

One thing we cannot stress enough is the value that we believe active management has in the Chinese bond market. Take local government bond issuance as a case in point. While there’s currently a large amount of divergence between various provinces on debt levels and yields, nearly all local government issuance has an implicit guarantee. This, in our opinion, provides ample opportunities for active investors.

The Chinese government’s role

Overall, we think the risks around Chinese debt for investors are a bit overblown. Why? One key reason is that a large amount of Chinese corporate debt comes from banks (not the bond market). Within this bank debt, more than half is from a state-owned lender to a state-owned enterprise.3 This provides the Chinese government greater oversight—and greater control—over leverage in the economy.

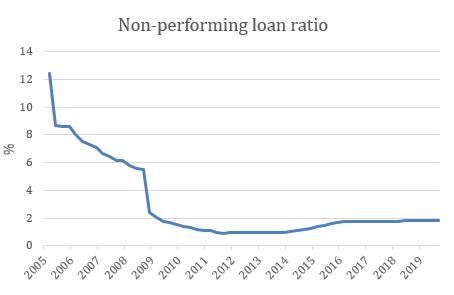

In addition, non-performing loans (NPLs), where financial stress would first start to show up, remains very low for Chinese banks. Given the dynamics of state-owned banks lending to state-owned enterprises, we would expect the Chinese government to be particularly sensitive to any rise in the NPL ratio.

Source: Bloomberg

Furthermore, the Chinese government has made deleveraging one of its key policy goals, while also maintaining steady growth rates (with a goal of doubling GDP per capita between 2010 and 2020). The recent cases of default show that the People’s Bank of China (the PBoC) is, in our opinion, willing to allow some failures in the corporate space to accelerate the maturing of the financial system. This can also be seen with the development of a bankruptcy system—something that previously was absent.4

Interest rates on the decline

Another reason why we think concerns over debt levels are overblown in the short-term is the decline of interest rates in China. The PBoC has been explicitly cutting rates, along with carrying out some reforms to the way interest rates are set. In addition, the PBoC has also introduced more competition to the banking sector—including penalties for price cartel behaviour—which will reduce interest rates that borrowers are subjected to.

The bottom line

At the end of the day, we don’t see the debt situation as likely to put too much strain on the Chinese renminbi. Instead, the key drivers will likely remain the state of trade negotiations between the China and the U.S., as well as the evolution of interest rates in China and the health of the global economy.

While we don’t believe there are good reasons to be panicking in the short-term, it’s worth noting that this build-up of debt will eventually act as a handbrake on Chinese growth over the long-term. Should the Chinese government ultimately desire to bring the country’s indebtedness down to levels near the global average, a significant amount of additional deleveraging will be required. On top of this, the Chinese economy will have to grapple with deteriorating demographics without the boost from urbanisation (as the rural population increasingly moves to the cities and becomes more productive).

One final question that remains unanswered, in our opinion, is how hard the Chinese government will push on deleveraging—and the timeframe with which they will approach it. A renewal of the country’s prosperity-focused goal of doubling GDP per capita would hint that the government is taking a steady approach to deleveraging. On the other hand, any indication from Chinese leaders that this goal has been achieved—with no extension needed—might indicate a risk that deleveraging efforts are likely to step up a notch.

3 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/24/business/china-downgrade-explained.html