The case for emerging markets

Emerging markets (EMs) have received a lot of attention of late – both positive and not so positive. In this article, we look past the current trends and market news that have impacted returns and revisit the case for a long-term exposure to emerging markets – specifically the drivers of growth.

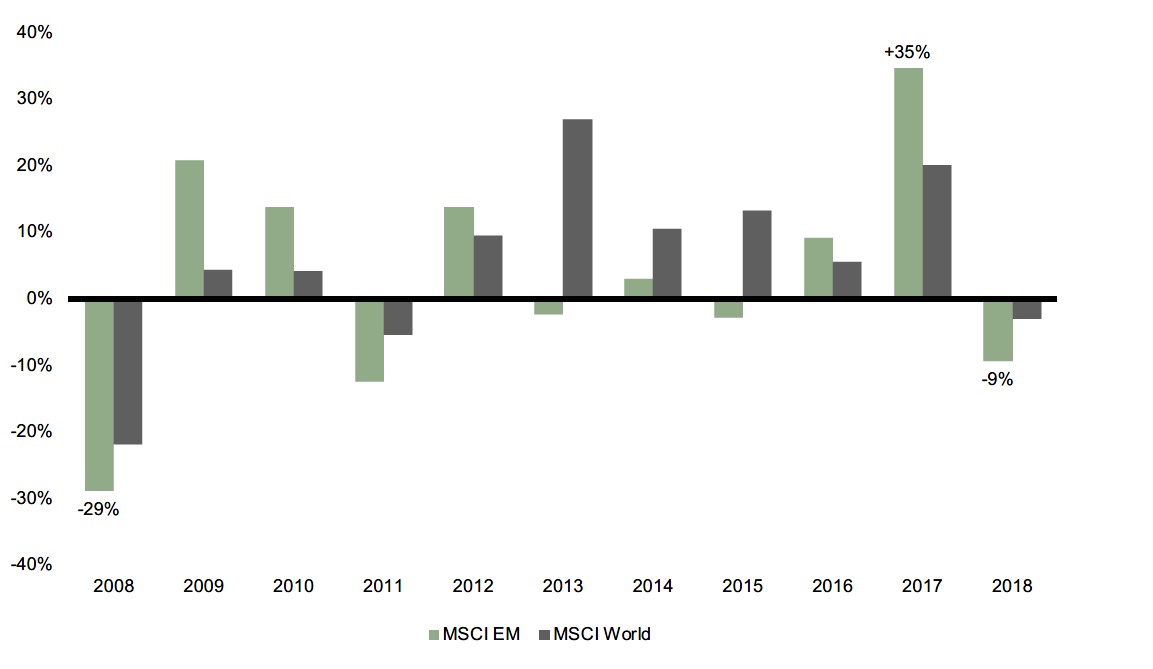

Emerging markets (EMs) have received a lot of attention of late – both positive and not so positive. Had this article been written this time last year, emerging markets would have been finishing 2017 with an eye-watering 35% return. However, as figure 1 shows, returns for emerging markets for 2018 were much less impressive with a high US dollar and tariffs collectively hurting these export-led markets. In this article, we look past the current trends and market news that have impacted returns and revisit the case for a long-term exposure to emerging markets – specifically the drivers of growth.

Figure 1: Calendar year returns (NZD unhedged)

First, what is an emerging market? Countries like Brazil, India, Indonesia, China and South Africa fall under the umbrella of emerging markets. The precise definition of these markets varies in the investment world, but generally these countries tend to have the following characteristics:

- Rapid economic growth: Emerging markets and developing economies have been experiencing real GDP growth of around 4.7% per year compared to 2.4% for advanced economies.1

- Low income per capita: China is the world’s second largest economy but has GDP per capita of US$9,600 compared to US$48,000 in advanced economies such as the US and Canada.1

- Immature capital markets: Emerging markets have a bigger proportion of companies that are unlisted (state-owned) and their capital markets tends to be less liquid. Corporate governance also tends to be relatively weaker in these markets.

Having defined emerging markets, let’s summarise the investment case for an allocation to these markets. The basic rationale is that, over time, as these economies transition from emerging to developed, they experience significant economic growth, driven by productivity gains, structural reforms and the rising middle-class. This economic growth widens the opportunities available to companies in these markets, improving their earnings potential and therefore the return potential for investors.

Long-term return drivers

Productivity growth

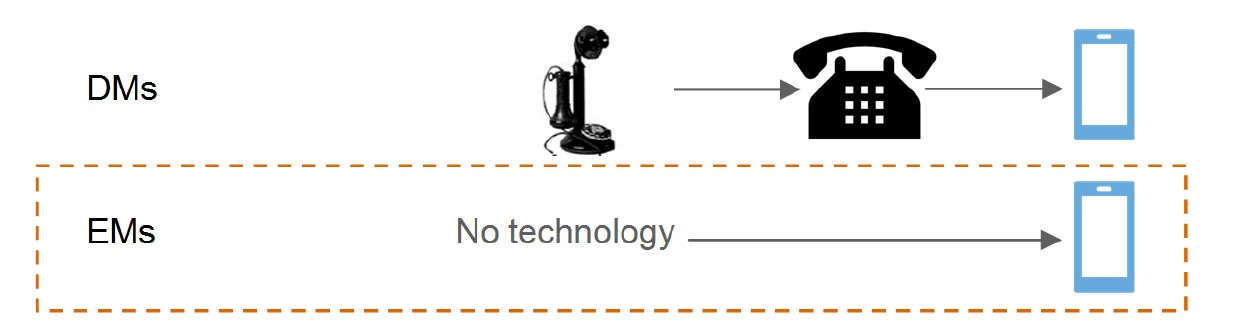

Productivity is defined as the output per unit of labour. Productivity growth in these markets is possibly best explained using the agricultural sector. Developed markets (DMs), like New Zealand, have over the years, replaced labour in agriculture with advanced machinery making agriculture more productive. In contrast, the transition from labour to capital is a much more recent phenomenon in emerging markets. This capital development has allowed them to move labour out of agriculture and into manufacturing, improving labour productivity and total output in the economy.2 Essentially, emerging markets are experiencing catch-up growth, whereby they are taking lessons from the developed world and applying them domestically. That is, they are importing technology. Figure 1 shows a simple example of this catch-up growth.

Figure 2: Leapfrog in technology

As shown in figure 2, developed markets have gone through phases of innovation in the telecommunications industry over decades – starting from phones with cords, building infrastructure along the way for each innovation, to where we are today with smartphones. Some emerging markets have bypassed the initial phases of phones and have directly adopted smartphone technology. The people using the technology have experienced a huge jump in productivity – going from no telecommunication to using smartphones to not only connecting but also using applications to conduct banking, invoicing and other business activities. The importing of technology allows the labour market to be more efficient enabling emerging market economies to produce more. It is this catch-up in technology that allows them to utilise their resources better and therefore grow more quickly than developed markets.

Structural reforms

In addition to achieving production efficiency, it is equally important to put in place political frameworks and economic structures that can not only sustain production efficiency but further enhance it. Developed markets are characterised as having transparent, less corrupt governments, where there is free trade and free flow of capital (i.e., prices are primarily determined by supply and demand). Developed markets’ political frameworks and economic structures promote allocation of resources to the most productive sectors of the economy with an overarching functioning government.

Figure 3: Structural reforms

As illustrated in figure 3, over time, emerging markets have moved structurally closer to developed markets by strengthening political institutions, reducing trade barriers, reforming agricultural and banking sectors and improving basic education. This has promoted economic growth.3 Some of the recent reforms in these markets include:

- In China, the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, which will connect China via transportation networks to Europe, the Middle East and Asia. The aim is to promote free trade and reduce trade costs. This will help stimulate economic growth by opening access to key industries.

- In India, the Government relaxed foreign direct investment regulations relating to its construction sector and rail network. These reforms have improved local infrastructure.

- In South Korea, the Government introduced a tax law to deter large businesses from hoarding cash on balance sheets without having efficient use for it. This will result in better shareholder protection and promote capital inflows, enhancing stock market liquidity.

Overall, as emerging markets move structurally closer to developed markets through reforms such as these, they have seen strong economic growth, experienced large flows of foreign direct investment and improvements in living standards (i.e., the rising middle-class).

Rising middle-class

The middle class are often referred to as the backbone of an economy. The middle class tend to spend a large percentage of their income feeding growth in the economy. The OECD defines the middle class as all those living with daily incomes of between US$10 and US$100.4

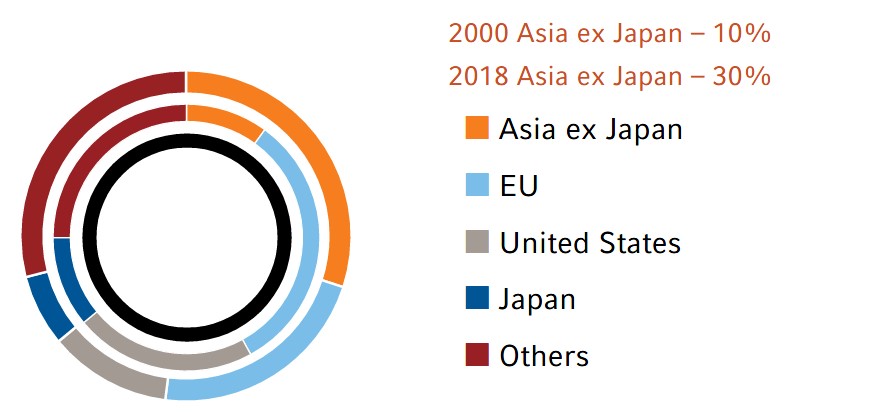

Figure 4: Shares of global middle-class consumption, 2000 - 2018

Source: The OECD

Figure 4 compares global middle-class consumption in the year 2000 with the 2018 forecast. In 2000, Asia excluding Japan made up around 10% of global middle-class consumption despite having most of the world’s population. In 2018, the middle-class consumption from this region is forecasted to be around 30%. As emerging markets shift labour out of low-productivity agriculture into manufacturing, the labour force sees an increase in output and therefore receives higher wages. The higher wages put them in the middle-class bracket. This is evident in, say, NZ and Australia as the number of tourists coming from China, for instance, has increased markedly over the last decade, simply because they have more money to spend.

So, why is this relevant to investors? The growing middle-income class has been a key driver of consumption growth. Generally speaking, as people experience an increase in income, they spend more. The spending opens new opportunities for businesses to improve earnings potential, driving valuations higher. This improvement in valuations has seen the cumulative flow of funds into emerging markets increase markedly over the last decade.5

Risk

No investment is without risk, especially in EMs. Some of these risks include:

- Political risk: these are government policies that are unfavourable, such as trade barriers and tariffs. There can also be expropriation through new taxation laws. Weak legal framework and copyright laws are also sources of risk.

- Poor governance: shareholder protection may be weak in EMs. Agency problems exists – the objectives of company CEOs may not be aligned with those of the shareholders. Getting access to good quality information may also be difficult due to weaker accounting standards and disclosure requirements.

- Liquidity risk: this comes in the form of currency controls in some markets. Currency hedging can also be costly due to lack of trading. Similarly, the buying and selling of stocks may incur relatively higher transaction costs as market accessibility maybe poor.

Conclusion

While risk management is at the forefront of most investors’ minds, generating strong returns from the growth component of a portfolio is still important. Emerging markets have experienced huge economic growth in the past but there is still a big gap in productivity with their developed counterparts. Emerging markets’ political and economic structures are yet to reach the standard of developed economies, and middle-class consumption is forecasted to increase further. Collectively, these long-term drivers of growth can turn into enhanced returns for investors. To re-emphasise the basic rationale for investing in emerging markets: as they shift from agriculture to manufacturing and then eventually services, the growing middle class will benefit those companies servicing this demand, driving valuations higher and therefore investor returns.

1 International Monetary Fund. (2018). GDP per capita, current prices. Retrieved from:

https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/BLZ

2 OECD. The future of productivity. (2015): 15.

3 International Monetary Fund. Anchoring Growth: The Importance of Productivity- Enhancing Reforms in Emerging Market and Developing Economies. (2013). 20. Retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2013/sdn1308.pdf

4 Kharas, Homi. 2010. “The Emerging Middle Class in Developing Countries.” OECD Development Centre Working Paper No. 285. Paris: OECD.

5 Institute of International Finance.