Cross-currency basis: An eventful year, but year-end should be quieter

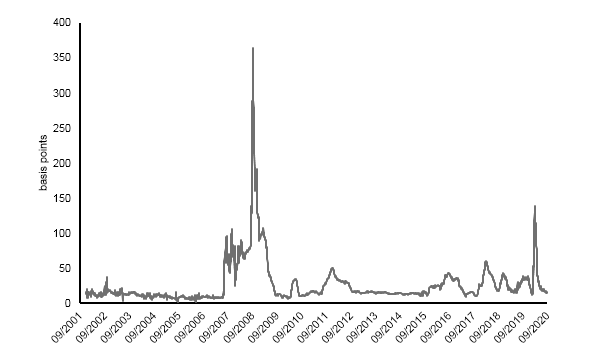

The volatility of the cross-currency basis was a point of focus throughout March and April, swinging wildly in either direction as funding stresses surfaced. A scramble for liquidity and dollars was, with impressive effectiveness, ultimately satiated by the handiwork of central banks, most notably the U.S. Federal Reserve’s flooding the monetary system with the pre-eminent reserve currency. The effectiveness and lasting impact of these actions became visible in Libor-OIS spreads1, cross-currency bases and the withdrawal in central bank take-up of U.S. dollar swap lines. While funding markets appear to be stable, the global economy remains in a precarious place. The U.S. presidential election is around the corner. The world’s geopolitical temperature is by no means cool and currency markets are still trying to figure out where we are headed. It is still important for investors hedging currency risk to remain aware of the cross-currency basis as a cost (or benefit) of hedging. It continues to have the propensity to move sharply.

Cross-currency basis through a liquidation event

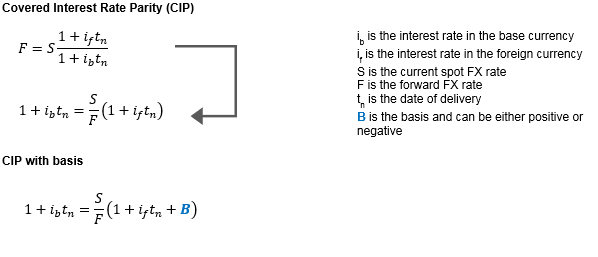

The cross-currency basis is the excess premium (or discount) factored into the quoted price of a basis swap (or an FX forward). It is the residual that theoretically shouldn’t persist beyond the very short term if the Covered Interest Rate Parity (CIP) condition holds. The CIP condition states that the forward rate of a currency pair should be the result of a simple calculation using the current spot rate and the respective short-term interest rates of each currency. Any residual is a signal that a risk-free opportunity exists, which should be swiftly arbitraged away. The basis is typically measured vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar and varies across horizons: long-term basis is a consequence of hedging demand, while short-term basis is a barometer of liquidity and credit risk sentiment.

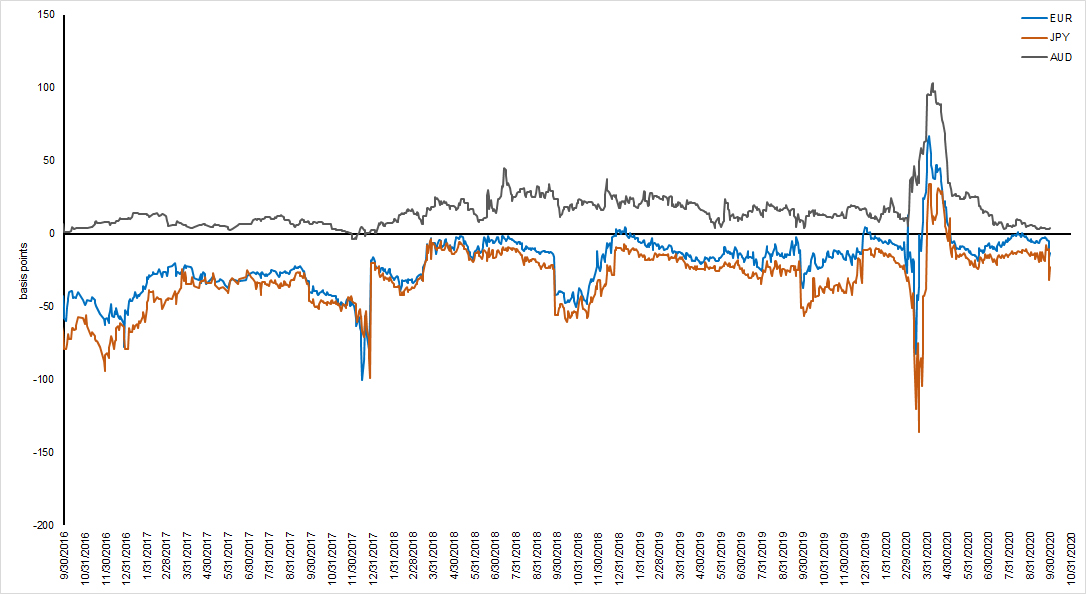

March of 2020 was unequivocally a liquidity event. The veracity of virus contagion initiated widespread selling of risky assets and a vicious rise in cross-asset correlations. Around the globe, investors demanded U.S. dollars, both for the safe-haven property and for dollar liabilities coverage. Liquidity was scant and credit risk sensitivity was elevated – panic had struck. As is usually the case, money market tightening crept into other funding markets, including cross-currency basis swaps and by extension other currency derivatives. Most non-U.S. investors hedging U.S. dollar assets were inflicted with a sharp adverse spike in basis, given the underlying structural funding supply and demand dynamics.

Click to enlarge

Figure 1: 3-month cross currency bases (EUR, JPY, AUD). Source: Bloomberg.

Episodic spikes in the basis have occurred several times since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the aftermath of which resulted in regulators worldwide instituting forceful reforms (e.g., Basel III, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision). It is, in fact, partly due to those same reforms that these episodes have occurred. Pressure on banks to improve conduct and hold more capital meant that the regulatory capital requirements of certain instruments on banks’ books became consequential. Seemingly erratic behaviour in the basis, over quarter- and year-end periods, has been underpinned by banks’ efforts to reign in their leverage ratios (comprising on- and off-balance sheet risks) in order to satisfy regulations. Some investors and currency managers have thus tried to transact ahead of key periods (especially year-end), or altogether side-step them, in an attempt to eliminate rollover risk by avoiding a December settlement date. Some opportunism has also been highlighted in the cross-currency basis swap space for certain regions, particularly Australia where an upward sloping basis term structure was used by investors - for example the Reserve Bank of Australia - to generate additional returns.

Deploying the monetary tools

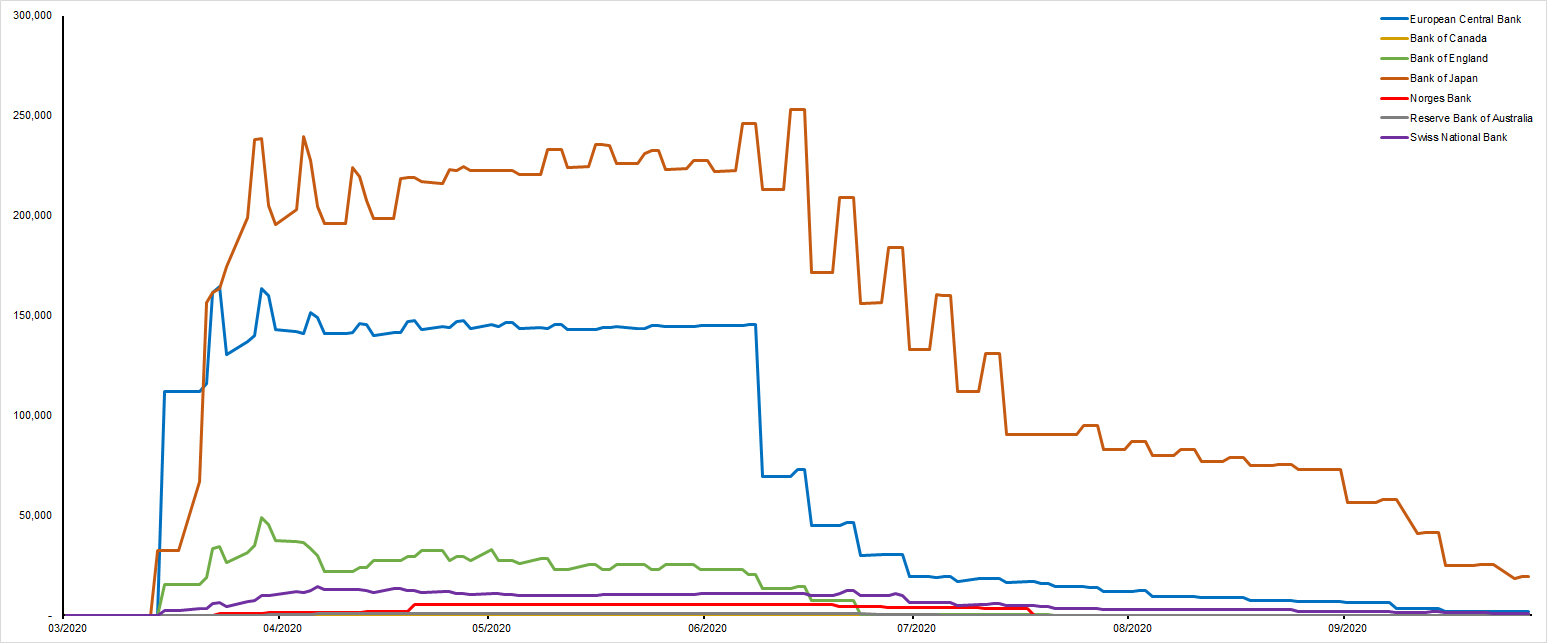

The basis tumult through March and April was not a product of regulation. An evacuation from risk, sparked by existential fear, created a liquidity event. The lender of last resort was needed and acted expeditiously. The U.S. central bank opened swap lines and repo facilities with various trading partners, backstopped the gridlocked credit markets and conducted quantitative easing, amongst a plethora of other initiatives. It was not alone, as other central banks unleashed liquidity into domestic markets.

The take-up in the U.S. dollar liquidity swaps was tremendous (see Figure 3). While investors remained trepidatious, funding markets stabilised in the ensuing weeks and months. The cross-currency basis and Libor-OIS spreads compressed back to more normal readings (see Figure 1 and Figure 2) and eligible central banks renewed gradually lower amounts of USD swaps with the Federal Reserve.

Figure 2: USD Libor – OIS Spread (3-month). Source: Bloomberg.

Click to enlarge

Figure 3: U.S. Federal Reserve Currency Swaps Outstanding by Counterparty. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Onward and wayward

As indicators show, volatility in the basis has settled. 2018 and 2019 saw euro basis gap down to around -40 basis points in the month of September. In 2020, while the basis did widen in the same direction at the end of September, it troughed at a much more muted level of around -16 basis points. The prospect of funding stresses re-emerging has not completely dissipated. But the Federal Reserve always has a choice – that is to be the domestic lender of last resort or the dollar lender of last resort. Adopting a position in the latter is not out of pure magnanimity. Instead, there is the recognition that instability in the Eurodollar market can be problematic through contagion. Costs and opportunities shall remain for investors, but for the time being, Fed support is in place. Most certainly, the U.S. central bank will vigorously want to avoid derailing a fragile economic recovery. With regard to the year-end turn, when the currency basis has in some previous years skyrocketed, a quieter transition from 2020 to 2021 would be welcome. Signs are promising that it will be a more benign year-end. The Fed recently extended its ban on bank share buy-backs, which means that banks will have plenty of excess capital and low yielding reserve assets into early 2021.2 This should incentivise U.S. banks to lend their excess dollars in the FX swap market, keeping the currency basis in calmer waters around the turn of the year.

1 The Libor-OIS spread is the difference between the London Inter-bank Offered Rate (Libor) and the Overnight Indexed Swap (OIS) rate.

2 Pozsar, Zoltan, 2020, “Global Money Dispatch”, Credit Suisse, 2 October 2020.

Any opinion expressed is that of Russell Investments, is not a statement of fact, is subject to change and does not constitute investment advice.