Is global diversification still worth it? The case for investing beyond the U.S.

We recently sat down to discuss global diversification with Dave Iben, chief investment officer and lead portfolio manager at Kopernik Global Investors. Dave plays a central role within the equity portfolios that Russell Investments manages for clients.

For U.S. investors, investing beyond America’s borders has been a tough sell over the past decade. Consider that for the ten years ending 31 March 2019, the U.S. equity market returned approximately 10.1% on an annualised basis - while non-U.S. developed markets returned just 2.7%. Emerging markets fared even worse, netting a meagre 0.7% gain.1

The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic has only amplified this pain, due in part to government stay-at-home mandates that have led to an increasing reliance on the technology and services offered by large U.S. technology-focused companies (e.g. Microsoft, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google). The U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed)’s slashing of interest rates to near zero in mid-March has potentially strengthened the appeal for U.S. equities over their international counterparts.

And yet, when broadening the lens out to a 10-year time horizon, Russell Investments’ long-term forecasts suggest brighter days are ahead for non-U.S. equities. In fact, by the end of this decade, Russell Investments is forecasting a 11% annualised return for non-U.S. equity markets and a 10.7% return for non-U.S. developed markets, compared to just 5.5% for U.S. equities.

Why? Because, as Kopernik’s Dave Iben points out, this time probably isn’t different after all.

The importance of value in the long-term

Everything looks good on the surface right now for U.S. companies, Iben notes. “Rapid technological advancement, central bank support and a comatose attitude toward antitrust in the U.S. are three key reasons why many investors still prefer U.S. equities, even amid the ongoing pandemic,” he said. Many still believe that this time really is different - that growth and tech stocks will continue their decade-long surge unabated.

Iben disagrees, saying that in the long-run, value shines through. “Value is actually pretty much all that matters long-term,” he noted, explaining that there’s a price for everything. This means that while good companies are worth more than less good companies, they're not worth an infinite amount. When you pay a high price for stocks, you get both a lower return and higher risk, Iben said. Why?

“Simply put, when things become too expensive, they generally don't stay that way. A look back through history at companies with the largest market capitalisations shows that those at the top don’t stay at the top forever,” he stated.

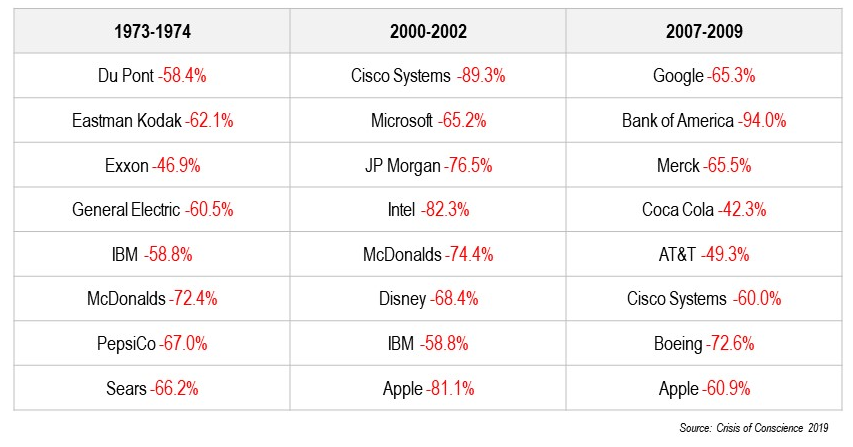

Click image to enlarge

The chart above solidifies Iben’s point, and is perhaps even more pertinent now, as the world struggles through the sudden and severe recession caused by the coronavirus. Iben noted that during the 2007-09 U.S. recession, Google stock lost 65% of its value, while Apple fell 61%.2

“We’ve all heard the saying that the four most dangerous words in investing are this time is different. And we all know how that generally rings true, as each cycle marches to the beat of its own drum. So, if this time isn’t different, history suggests that these large U.S. tech stocks and other quality growth stocks, could potentially experience multiple years of relative underperformance,” he observed.

Leadership rotates

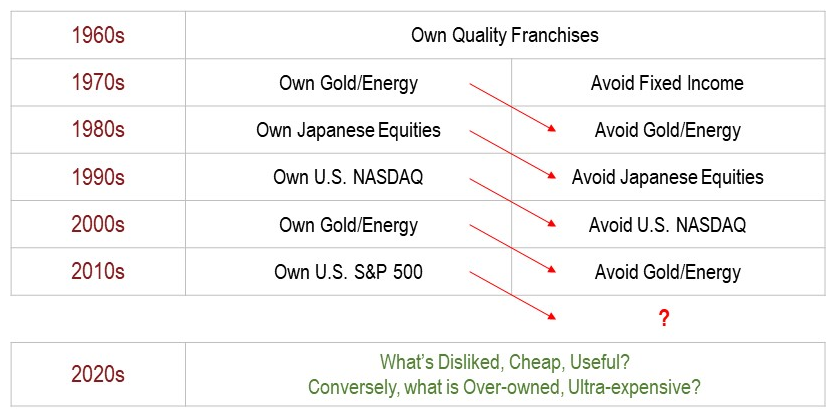

Often, what was a good investment in one decade turns into a bad investment the following decade, as shown by the chart below. For example, in the 1970s, gold and energy performed very well - yet by the 1980s, both had become key asset classes to avoid. Similarly, in the 1990s, investors flocked to U.S. NASDAQ stocks - only to flee them en masse in the 2000s.

Click image to enlarge

Could this mean that U.S. S&P 500 stocks, which has been the asset class to own during the 2010s, might fall out of favour this decade? History certainly suggests there’s a case to be made, Iben said - and he believes this trend could start unfolding sooner than later.

“I would suggest to anyone looking at the fundamentals right now, that it’s going to be hard to cash in on U.S. growth stocks. I simply don’t see where the additional growth is going to happen.” Iben said.

A world of bargains outside the U.S.?

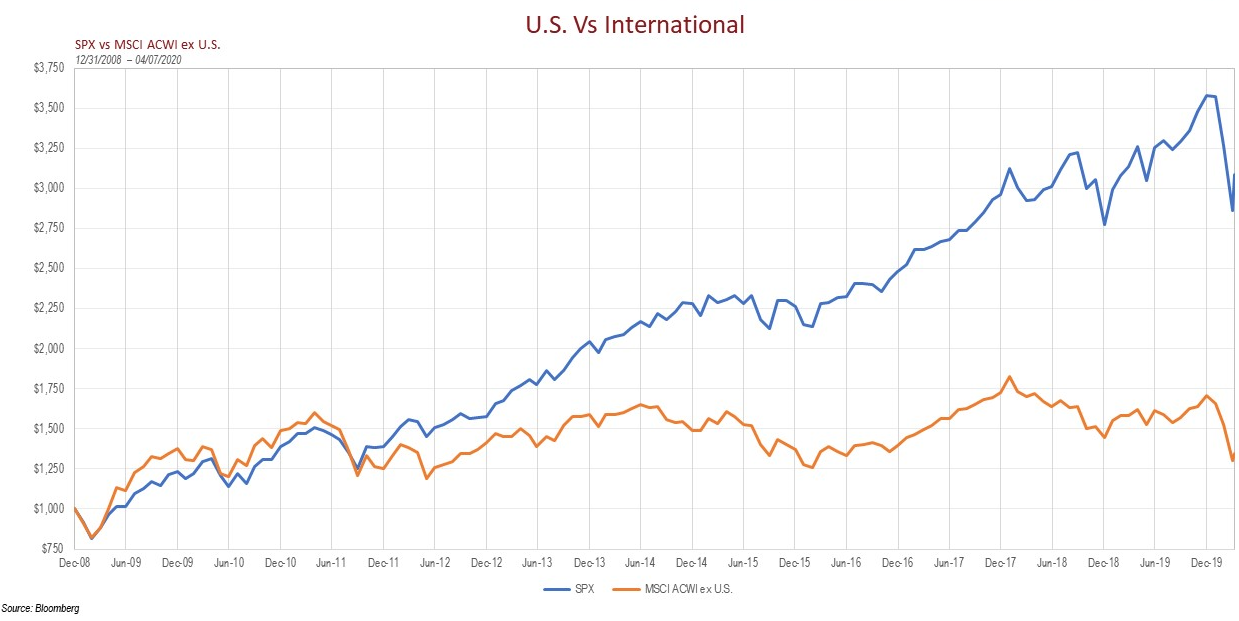

Iben said that, even putting concerns over U.S. growth stocks aside, it’s simply too hard for him to ignore how cheaply valued non-U.S. companies have become. The chart below, which pits the performance of the S&P 500 against the MSCI All-Country World Index ex-U.S., demonstrates this well. Over the past 11 years, international stocks have essentially seen no gains in value, while U.S. stocks have charted a meteoric rise.

Click image to enlarge

This begs the question, Are there really no international companies that have done well over the past decade? In the entire world, are there truly no good companies outside the U.S.?

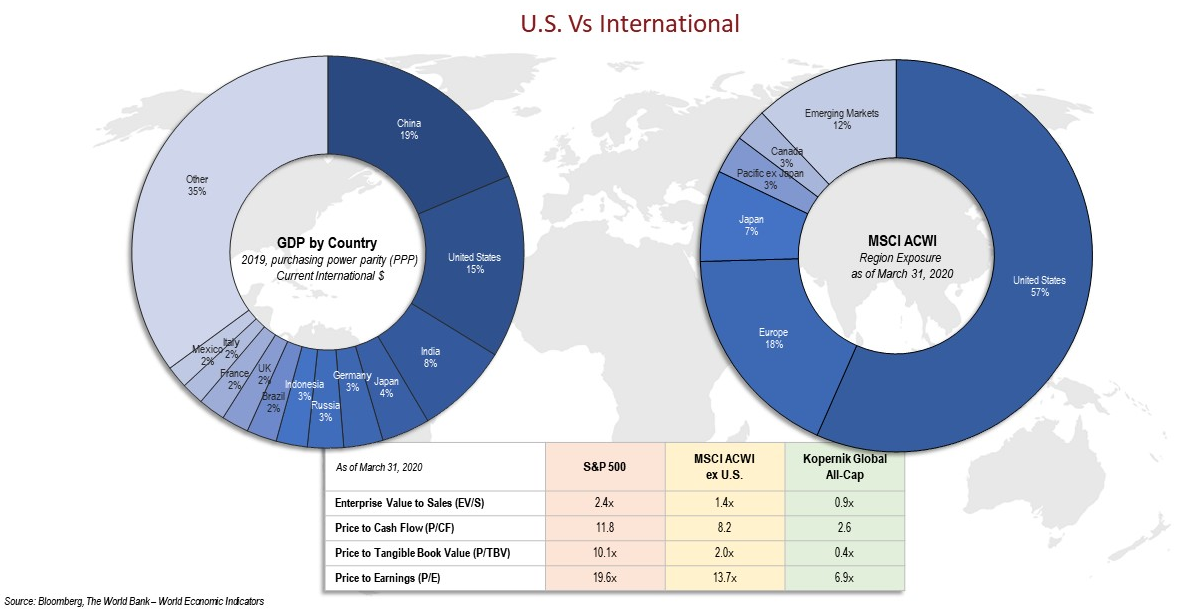

“I’d strongly suggest that for investors who are willing to pick and choose among non-U.S. companies, there are bargains to be had that are being missed,” Iben said. The discrepancy between stock prices in the U.S. and the rest of the world has become so large, he noted, that a whopping 57% of the MSCI All-Country World Index is comprised of U.S. companies. And yet, the U.S. only captures 15% of the world economy per share of GDP (gross domestic product).

Click image to enlarge

Simply put, that’s a massive overallocation of capital to one country, Iben said. Another way to think of this is that emerging markets comprise just 12% of the MSCI All-Country World Index. Yet, emerging markets make up most of the world’s population, most of the world’s land and most of the world’s countries. In fact, they comprise more than half of the world’s GDP.

This is why Iben and his team disagree with the view that emerging markets are a sort of niche. “We don’t view the asset class as a niche, we view it as most of the world,” he stated.

While the discounts offered elsewhere across the globe are noteworthy when compared to the U.S., Iben said that some of these variances in price are warranted. After all, the U.S. is a prosperous country without the political and economic risks that often plague many emerging-market countries. But even when factoring in risk-adjusted valuations, the differential is simply too great, he said. “Even when my team bakes in discounts to account for risk, emerging-market valuations are still quite cheap,” Iben stated.

The worth of U.S. companies versus countries

Another way to put the value that non-U.S. markets may offer into perspective is by assessing the worth of countries against the worth of U.S. companies, Iben said.

Click image to enlarge

Surprisingly, the top four U.S. companies by market cap - Microsoft, Apple, Amazon and Google-parent Alphabet - are all valued more together than the economies of Canada, South Korea, Brazil and Russia, which are all among the top 12 economies in the world.2 Let that sink in for a moment, Iben said. Just two companies based in Seattle (Microsoft and Amazon) have a higher combined market cap than all of Canada. Would you really pay more for a U.S. company than a top-12 world economy?

Consider the size of some of these countries alone, Iben said. Russia and Canada are the two largest countries in the world, whereas Brazil is the fifth-largest. Combined, these three countries make up 23% of the world’s land mass.3 This means they contain a disproportionately large chunk of the world’s resources. And when it comes to population, Brazil is the world’s sixth-most populous nation, and Russia isn’t far behind at number nine.4 South Korea, meanwhile, is a global leader in technology and home to multinational conglomerate Samsung.

“Let me be clear: in my opinion, no matter how good a company is, it’s never worth more than a major world economy,” Iben stated.

The bottom line: Patience is the name of the game

Iben believes that investors are well positioned if they exercise patience and wait on non-U.S. companies to take off. He notes that the collection of non-U.S. companies with strong upside potential is the highest he’s seen in his nearly four decades in the industry.

Make no mistake, Iben added, investing outside the U.S. today means being a contrarian, and being willing to be unpopular for a short period of time. But, he remarked, this is the very reason such opportunities exist.

“If investing outside the U.S. were that easy, everyone would do it. It’s never easy to stick your neck out from the crowd, especially in today’s times. However, I believe both history and logic suggest that doing so is worth the short-term pain, because the long-term gains can be pretty significant,” Iben concluded.

Any opinion expressed is that of Russell Investments, is not a statement of fact, is subject to change and does not constitute investment advice.

1 Source: S&P 500 Index, MSCI Emerging Markets Index

2 Source: "Crisis of Confidence," 2019

3 Source: https://www.investopedia.com/insights/worlds-top-economies/

4 Source: https://www.worldometers.info/geography/largest-countries-in-the-world/

5 Source: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/population-by-country/