U.S. midterms update—and potential market implications

Polls have officially closed in all states, but it will take some time for the final results to be tabulated. As of 9 p.m. Pacific time on Tuesday night, it appears that the Republican party may win control of the House of Representatives. Meanwhile, it looks like the nation will have to wait even longer to see which party controls the Senate, as polling for many of the pivotal Senate races looks extremely tight. The tallies in Nevada, Georgia, Pennsylvania, Arizona and Wisconsin, in particular, bear close watching.

As we wait for more results to come in, it’s fair to say that, depending on your political affiliation and interest level, these next few days may be either exciting, scary, important, or boring. For what it’s worth, my in-laws are visiting, and a feature of recent dinnertime conversations would have me believe that the world is coming to an end (or not) depending on the outcome. Politics are emotional. Investing shouldn’t be. Let’s stick to the facts and what matters and what doesn’t for markets.

Republicans need to gain five seats to win back the House—and most political forecasters have them winning far more than that. In the Senate, meanwhile, there is zero room for error for the Democrats. If Republicans win just one seat, they will gain control of the upper chamber. While it looks like the balance of power in the House will be determined more quickly, we might not know the outcome in the Senate for days—if races are tight in states that are historically slow to tabulate their results (e.g., Pennsylvania)—or weeks if (another) runoff election is required in Georgia on Dec. 6.

That’s enough on the logistics for today. What does it mean? Not much.

Could the election results change the U.S. outlook? It’s unlikely

First, it’s the economy stupid. Yes, there is a midterm election. But we are also at a pivotal point of the business cycle where the U.S. Federal Reserve is on a warpath against high inflation, 30-year fixed mortgage rates have more than doubled, leading economic indicators are slowing, and equities and government bonds are down double-digits this year. I’d be willing to bet a cookie that we are writing about how those key macro-market risks evolve—not the midterms—a year from now.

Second, the midterms are unlikely to meaningfully change the U.S. fiscal or economic outlook. As noted above, early results suggest Republicans are likely to gain control of the House, resulting in a divided and gridlocked government. The Senate outcome is largely irrelevant for markets in this scenario, as the combination of our polarized politics and the power of the presidential veto suggests very little new legislation would get done. Maybe that simple view is wrong. Let’s look at what the Republicans want to do. House GOP Leader, Kevin McCarthy, gave an interview last weekend where he outlined his party’s top priorities, including border security, fighting crime and fighting inflation. And yet the last—fighting inflation—is arguably the only issue of consequence for asset prices. Democrats are already there. The rebranding of Biden’s signature Build Back Better bill to the Inflation Reduction Act suggests to me the days of big U.S. stimulus were already over irrespective of who is in power. In the unlikely scenario that Democrats retain/gain more control in Congress, markets may need to consider the outside possibility of higher corporate taxes, which would be a negative for equities. But again, these effects are likely to be small and quickly overwhelmed by other more important macro and geopolitical catalysts.

There are a few wrinkles I think about around this otherwise mundane view. There’s an old Winston Churchill quote that “generals fight the last war.” The lesson from the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-09 was that policymakers, particularly in Europe, did not do enough to promote a strong recovery. Enter COVID in 2020. U.S. and global policymakers went all-in with their most aggressive fiscal campaign since World War II. The lesson from COVID (so far, rightly or wrongly) is that policymakers overstimulated and created an inflation problem. I worry that the lesson from this for the next recession will be less support and a slower recovery. That is a concern in all political configurations but particularly in a divided government. The other wrinkle to consider is the debt ceiling. McCarthy has stated that Republicans will demand spending cuts in exchange for lifting the debt ceiling. As unlikely as a technical default is, the headlines and volatility from political brinksmanship might make an unwelcome comeback.

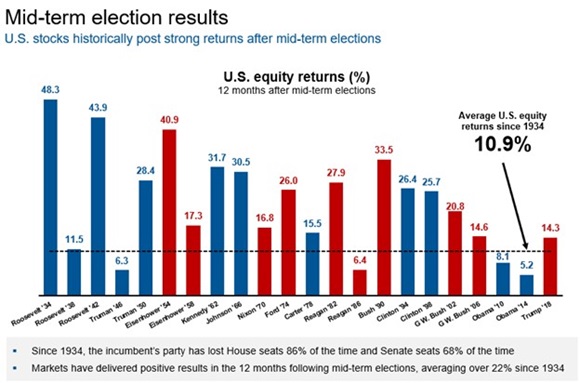

Source: The American Presidency Project & Morningstar Direct. U.S. Equity: S&P 500 Index (1/1/1935-8/31/2022) and Ibbotson SBBI U.S. Large Stock Index in prior years. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment. 12 Month Forward Return: November 1 to October 31 of the following year.

How do markets typically fare after midterms?

But those are small potatoes. Let’s wrap with a quick look at the historical record on how markets behave in the year following midterm elections. These analyses are a dangerous conflation of correlation and causation, but in every case dating back to 1934, forward returns have been positive. If you slice the data even further, the configuration of a Democratic president with a Republican or split legislature has fared even better than this long-term average. That might be a random artifact of history or it might show that elections resolve uncertainty and markets don’t like uncertainty.

The bottom line: Keep your politics out of your investing. Stay focused on your long-term plan. Stay invested.