Credit Downgrade: Markets Poised to Shake It Off

America’s fiscal woes are nothing to sneeze at, but they’re also nothing new. Which is why we expect markets to largely shrug off the latest credit-rating cut.

On Friday, Moody’s cut the United States’ long-term credit rating from Aaa to Aa1—matching similar moves by Standard & Poor’s in 2011 and Fitch in 2023. Moody’s cited persistent, large budget deficits for the move.

Markets took the decision in stride. The S&P 500 Index closed up slightly on Monday while the 10-year Treasury yield was little changed with the curve bear steepening.

Upheaval Unlikely

We see three reasons why the ratings action is unlikely to be particularly disruptive to markets.

1. It’s old news

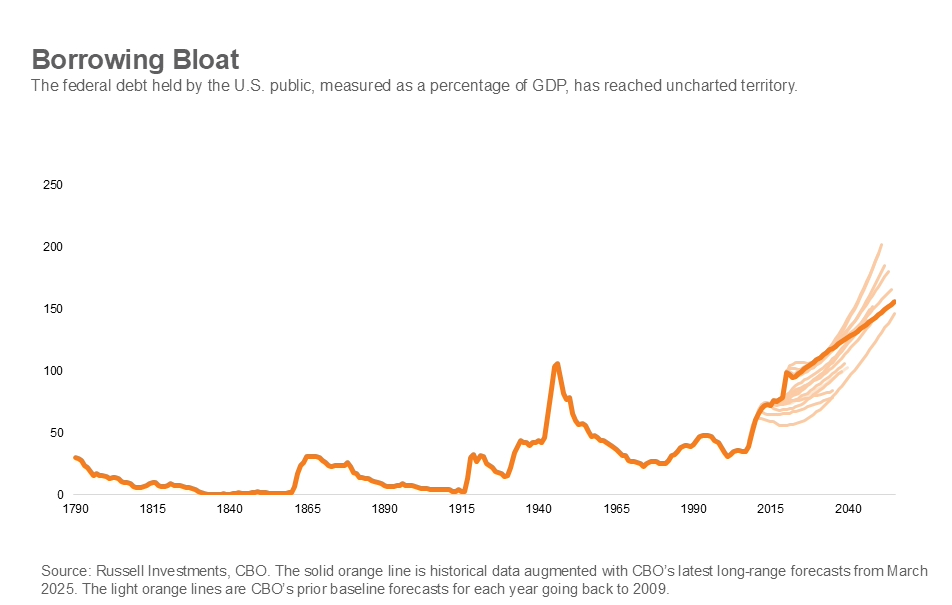

The idea that the U.S. is on an unsustainable fiscal path is not new news. Every Fed Chair since Alan Greenspan in the mid-2000s has called out the problem in front of Congress. At the heart of it—underfunded entitlement programs and rising welfare costs as the population ages. This has been a slow-motion trainwreck for economists tracking the issue. For example, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office’s long-term projections have consistently showed a hyperbolic debt trajectory in the 2030s and 2040s. Higher interest rates post-2022 simply amplify this underlying dynamic.

2. Markets are forward-looking

Our fixed income strategy team discussed how to price these fiscal risks onto long-dated Treasurys leading into and following the “red wave” election outcome last November. We pushed our estimate of the fair term premium on long bonds higher and have seen that come through in markets. Most models place the “risk premia” on U.S. bonds—the extra return required by investors to hold them—at the higher end of its post-financial-crisis range, at around 0.75%.

3. We don’t expect forced selling

Our trading desk flags that many investment guidelines were rewritten back in 2011 to prevent forced selling of positions in the instance of further ratings downgrades. Furthermore, Moody’s left the country ceiling for the United States at AAA, allowing the highest quality corporates (e.g. Microsoft, Johnson & Johnson) to retain their highest ratings marks.

Risks Ahead

None of this is to sneeze at the long-term fiscal challenges of the United States. They’re real. It’s just a known problem. What catalysts could accelerate the pricing of these risks into markets?

First, President Trump’s so-called “Big Beautiful Bill” is currently working its way through the House of Representatives. If markets judge it to be too inflationary, that could cause a riot in the bond market. For now, the bill’s impacts look modest—boosting growth by only a few tenths of a percent.

Second, later this decade Congress could be forced to deal with our much thornier entitlement problems, as the trust funds backing Social Security and Medicare are expected to run down their assets in 2035 and 2036, respectively. Without reform, program recipients would face an immediate reduction in benefits—a politically unpalatable situation that could catalyze long-needed action from Congress.