New Zealand Bonds Underperform, Though There May Be a Silver Lining

Investors in New Zealand bonds have suffered over the last couple of years as the local market materially underperformed global bond markets. This underperformance is clearly illustrated by the material negative return earned on New Zealand bonds over the last three years compared to a modest positive return from global bond markets, i.e. -1.42% p.a. versus 0.23% p.a. respectively for the three years ended April 2020. Though there are a range of factors which have contributed to this outcome, one of the more significant is the position of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) in the monetary cycle relative to other central banks. Fortunately, it is this very difference in the relative positioning in the monetary cycle which provides a potential silver lining for the New Zealand bond market moving forward.

To better understand the dynamics at work, it is useful to recap briefly the events caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact these had on the policy reaction functions of central banks. In response to the pandemic, many of the world’s central banks embarked on quantitative easing programs to support their respective economies in the face of supply-side shocks and the adverse effects of government policies aimed at mitigating the spread of the virus and its derivatives. The more recent issue arising from these supply shocks has been an increase in inflation due to supply-side disruptions. These supply-side disruptions have been exacerbated by the increase in energy prices arising from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and associated global sanctions. Though inflation has risen well above the inflation targets of central banks, including the RBNZ, officials were prepared to look through this when setting policy based on the view that the surge in inflation was transitory. With central banks looking through the rise in inflation, the focus of central bank policy reaction functions turned to the real economy – notably the unemployment rate and potential wage inflation – to gauge the longer-term underlying inflationary pressures.

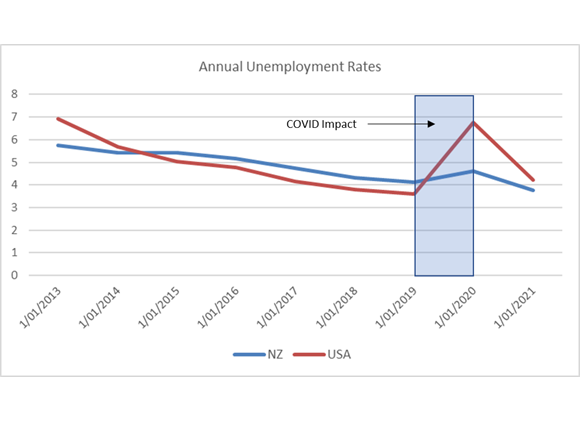

In New Zealand, the economy, due to a range of factors, was in a stronger position to recover as the world moved into a post-lockdown environment. This was partly driven by New Zealand not experiencing the increase in unemployment that we saw in other countries, including the US.

Figure 1:

Click image to enlarge

Source: Bloomberg

The smaller adverse impact on the unemployment rate not only put the New Zealand economy in a stronger position to rebound coming out of lockdown, but also resulted in intensified price pressures within the housing market. Though New Zealand was not the only country to see rising house prices as a by-product of quantitative easing policies, it did become more politically sensitive. Due to this heightened political sensitivity, in February 2021 the Minister of Finance provided direction that “requires the Bank to have regard to the impact of its actions on the Government’s policy of supporting more sustainable house prices, including by dampening investor demand for existing housing stock, which would improve affordability for first-home buyers.”

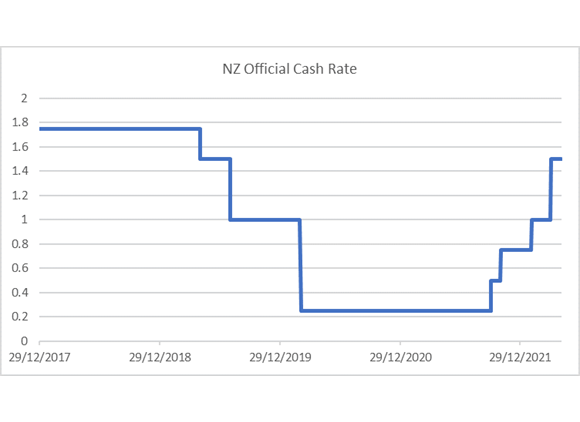

It was against this backdrop that the RBNZ began to raise rates from the low of 0.25% in October 2021. More importantly, not only did the RBNZ begin to raise rates, but the pace at which they raised rates was quite rapid, with the official cash rate reaching 1.50% in April 2022.

Figure 2:

Click image to enlarge

Source: Bloomberg

Such a pace of rate rises signalled the RBNZ’s intention to not only unwind quantitative easing, but to frontload the rate rises to provide sufficient flexibility moving forward. Specifically, the RBNZ noted in its announcement on 13 April 2022, fittingly entitled ‘Monetary policy tightening brought forward’, that “a larger move now also provides more policy flexibility ahead in light of the highly uncertain global economic environment.”

In raising rates early and aggressively, the RBNZ placed itself at the forefront of central banks with respect to the normalisation of interest rates. With central banks such as the US Federal Reserve and the Reserve Bank of Australia only now starting to raise official cash rates, the RBNZ is at least six months ahead of its peers. While on the plus side this has provided the RBNZ with the desired policy flexibility, on the negative side it also pushed longer duration bonds in New Zealand higher ahead of other countries. It was this difference in timing which provided a material tailwind to the New Zealand bond market and contributed to the material underperformance over the last couple of years.

The point to note is that the difference in timing between central banks in the pace of normalising interest rates is just that: a difference in timing. Whilst at the margin there may be differences in the ‘neutral’ cash rates associated with the achievement of central bank policies, there is little reason to believe that there are material differences for central banks within developed countries. Whilst there is much debate on the topic, and ultimately only real-world experience will prove where it is, there is a convergence of opinions that the neutral cash rate lies somewhere around 2.0%. If this proves to be the case, then the RBNZ will be one of the first central banks to normalise cash rates by moving back to the neutral cash rate. For investors in the New Zealand bond market, this provides a silver lining, as the underperformance experienced to date has been partly driven by the RBNZ being ahead of other central banks in this normalisation process. This provides scope for New Zealand bonds to outperform as the RBNZ slows the future pace of rate rises while the rest of the world’s central banks play catch up. So, just as the relative pain endured by bondholders due to the RBNZ being ahead of other central banks has been frontloaded, so too may the benefits moving forward.