Guarding against mindless investing

As we all know, investing money can be challenging at the best of times. We have previously discussed the impact that human behaviours can have on financial outcomes, especially when presented with uncertain or stressed markets.

As the global pandemic has presented us with increased volatility and uncertainty, we thought it would be beneficial to revisit some of those behaviours, remind ourselves of the risks they can present and how to combat them.

Behavioural bias: What drives investors to select one response over another?

This is dependent upon a number of factors: the investor’s objectives, including their risk tolerance and return target and the investor’s beliefs on market cycle positioning and the potential market outcomes during that time horizon. Depending on investor’s beliefs, preferences, emotions and past experiences, they can come to contrasting conclusions. This results in different investor behaviour and sometimes opposing investment strategies.

Humans are human

Human beings are not machines. Traits such as overconfidence, narrow framing and loss aversion are well-documented and can impact how investment decisions are made, contributing to errors such as buying high and selling low. Investors should not ignore human nature and rather find ways to work with it, taking practical steps to create better investment outcomes for their clients.

Houston, we have a problem

Our brain is an incredible organ, it processes over 11 million pieces of information every second – yet sometimes, our brain fails us. It can lead to the wrong answers or desert us altogether. We have two parts to the brain: the intuitive and automatic side, known as the Blink side. The other part of the brain which is reflective and rational, is known as the Think side. Investment professionals can often end up trusting the initial Blink side of the brain, which provide emotional reactions to issues and only occasionally do we recruit the Think side of the brain and use more rational actions to review our decisions.

What sorts of behaviour does this drive investors toward?

Loss aversion refers to an individual’s tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains, the pain they experience from the loss is nearly twice as strong as the pleasure from the gain, resulting in wanting to avoid losses more than seek gains. In February and March 2020, global equities experienced their fastest ever 30% decline. Investors selling their investments at this point, would have missed out on the subsequent recovery (as of 16 November, MSCI World in GBP terms is not only recovered all the loses from earlier in the year, but is at above its highest level pre COVID-19).

Overconfidence -Recognising the potential brain flaw in ourselves can help us relate better to our clients. When investing, overconfidence often translates into trading a lot and having high portfolio turnover. Overconfidence investors tend to trade more. They may also tend to be more thrill-seeking: drawn to trading because of its perceived entertainment/gambling-like value.

Herding - You’ve seen it happen and have probably spent time talking clients out of this instinct to chase returns.

In December 2010, U.S. investors pulled $10.6 billion out of U.S. equity mutual funds. Then in 2011, someone hit a switch: that month, we poured an estimated $30 billion into the market. Investors had decided that it was time to get back into stocks. This decision came after an almost 100% gain from the market bottom in 2008. By the time investors can identify a clear trend of the past in order to extrapolate it into the future, they have missed most of the move.

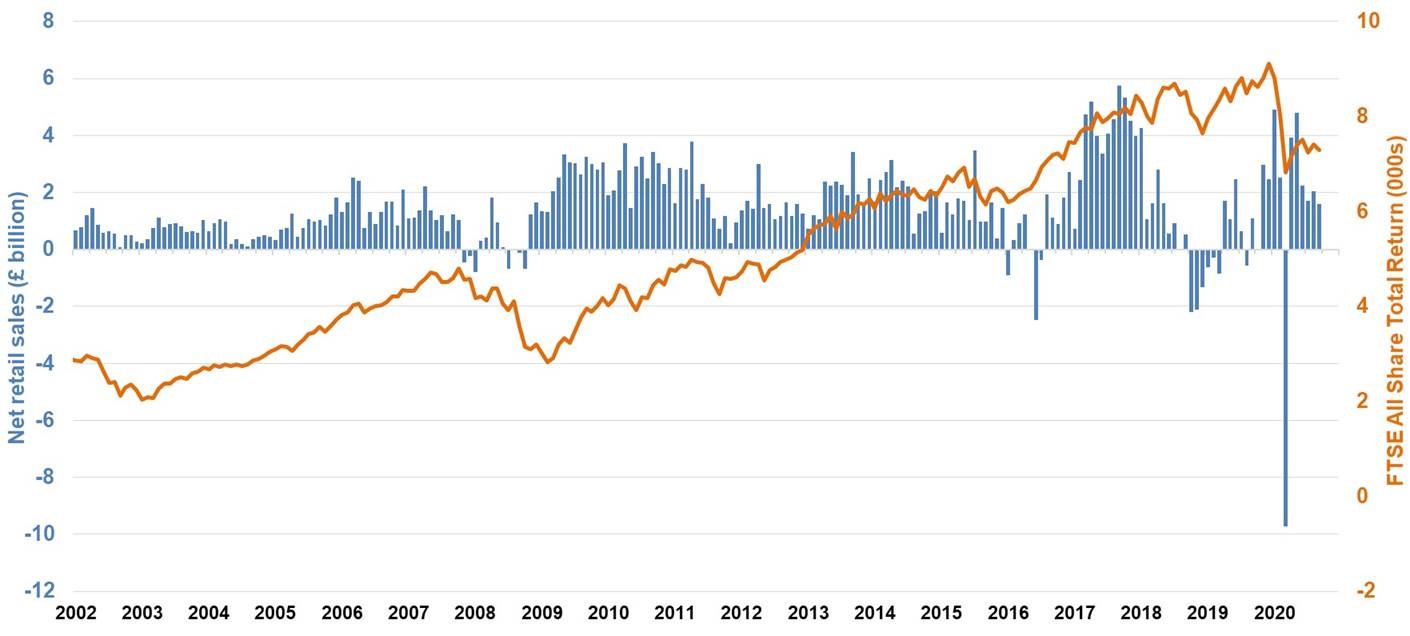

A more recent example is in March 2020, the below chart shows the largest outflow on record for UK net retail sales. Unfortunately, this bias leads an investor towards buying high and selling low, not a winning investment strategy.

Source: The Investment Association and FTSE All Shares Index Total Return, September 2020.

Familiarity bias - Think back to your most recent trip to the supermarket – despite the vast amount of choice most of the time, we arrive in the same aisles and we stick with what’s familiar to us. What does this behavioural bias look like when we are investing? It can have an impact on our decision-making process, missing out on potential return opportunities as we are blinded by familiarity.

The value of working with an adviser

These common behaviours are predictable; what’s predictable can be managed. As humans, we all suffer from some biases. But many of these can be reduced by a robust, objective and disciplined process. The first step is to recognise and openly accept our biases. Take decision-making seriously and recognise that sometimes it’s the decisions you choose not to make that count more than the decisions you do make.

Any opinion expressed is that of Russell Investments, is not a statement of fact, is subject to change and does not constitute investment advice.