B is for behavioral mistakes—Preventing them may be your greatest value

You’ve heard us say it before, but we’re saying it again: Russell Investments believes in the value of advisors. And we believe communicating that value to your clients is more important than ever. That’s why we propose this simple formula:

In the first blog post in this five-part series, we discussed the value of annual rebalancing. In this post, we’ll tackle the behavioral mistakes that investors typically make.

Coaches win championships

During our decades of working in this industry, we’ve heard directly that most advisors spend the bulk of their time trying to minimize their clients’ behavioral mistakes, especially when markets become volatile. We like to hear this, because our own value of an advisor study shows that taking on the role of behavioral coach may be the most important role a financial advisor can play. Most advisors know far too well that investors don’t always do what they should. Instead, their behavior is sometimes directly opposed to what is in their own best interests.

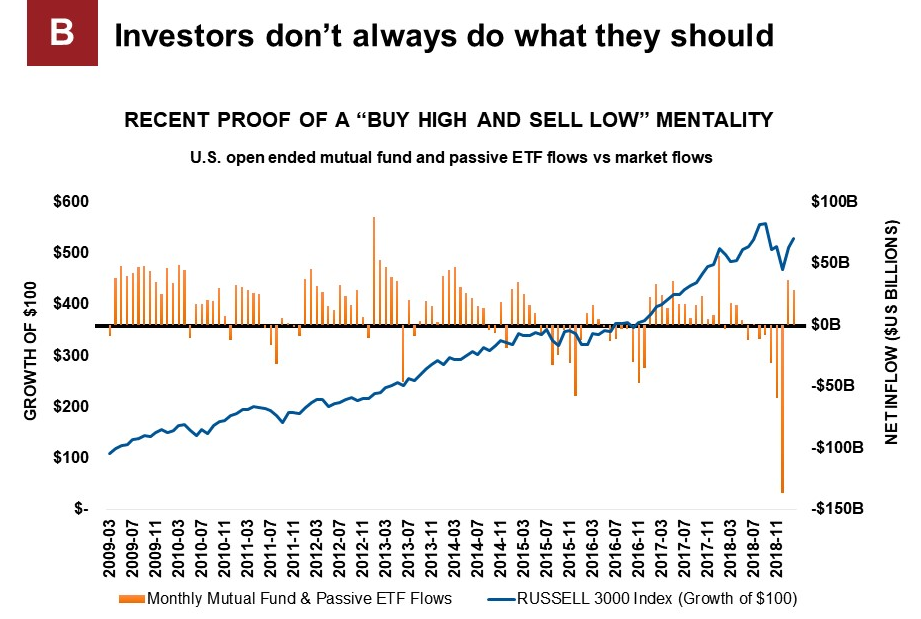

Check out the chart below. With history as our guide, we can see that investors have made a lot of human mistakes. On this chart, the bars above the horizontal line represent net inflows of investor money into the U.S. stock market; the bars below the horizontal line indicate net outflows of investor money from the U.S. stock market. At the same time, the blue trendline shows the Russell 3000® Index going bubbily up to the right, increasing in value at a relatively steady pace between March 2009 and the end of February 2019.

Click image to enlarge

Data shown is historical and not an indicator of future results. Sources: Monthly mutual fund, passive ETF flows and Russell 3000® Index, Morningstar, Direct. Data as of February 28th, 2019. Index performance is not indicative of the performance of any specific investment. Indexes are not managed and may not be invested in directly.

Investors, like all humans, look for patterns, even when they shouldn’t. And sometimes, looking for patterns can get investors into trouble, especially when their pattern-chasing inclinations cause them to make the wrong decisions at the wrong times. They also tend to follow the herd. Left to their own devices, we believe this chart shows that the investor herd, overall, is inclined to leave the market when it is down like in the summers of 2011, 2015, 2016, and the end of 2018—meaning investors tend to sell low. And the herd tends to enter the market when it is up—meaning investors tend to buy high.

Obviously, this investor behavior can hurt investor returns. While we can’t control the markets, sometimes we forget that what we can control—or at least help control—is this very behavior. Practically speaking, if an investor’s personal situation really hasn’t changed, then staying the course and riding through these periods of volatility is the logical course. But that is humanly hard. We believe having an accountability partner, like a skilled financial advisor, gives the investor a significantly better chance at making good decisions during periods of both emotional and market volatility.

Behavioral economics: Where finance and psychology meet

Behavioral economics is the academic body of work that recognizes the difference between what human investors should do and what they actually do. This is where traditional finance and economics meet psychology.

Click image to enlarge

One of the key beliefs of behavioral economics is that changing bad investor behavior begins with awareness. Think about how tracking your daily number of steps with a Fitbit can increase the number of steps you walk each day. The power of the Fitbit is the awareness it generates. For your clients, behavioral change begins with personal awareness of their investing behavior—of the investment biases that may be causing their mistakes. Once our clients are aware of these biases, you, the advisor, can be that accountability partner to help them stay on course.

Five common investment biases

Within the science of behavioral economics, there are over two hundred identified biases that impact money decisions.* Here are the five we consider to be the most common—and the most important for advisors to address.

- Loss aversion – Humans tend to prefer avoiding losses more than acquiring equivalent gains. In other words, the pain of loss is a more powerful force than the gratification of gain. This fear of loss may cause your clients to want to sell winning securities too early. And the fear of missing out may cause investors to hold onto losing securities too long.

- Over-confidence – Investors tend to over-estimate or exaggerate their ability and expertise. In other words, they tend to believe they are experts when they are not. Their belief in their ability to time the market, for example, may cause them to trade too often or at the precisely wrong time. Or their belief in their ability to identify opportunities may cause them to risk too much exposure on a perceived hot stock.

- Herding – Humans tend to mimic the actions of the larger group. When the herd tends to sell and pull out of the market, individual investors tend to join in, even if it means selling low. When humans tend to buy, individuals tend to jump on the bandwagon, even if it means buying high.

- Familiarity – Humans tend to prefer what is familiar or well-known. We see this in the way investors tend to overweight their portfolios toward their home countries, even when there might be a recommendation to diversify globally.

- Mental accounting – Investors tend to attach different values to money based on its source or its use. Think about how an additional $5 for rent feels like a little, but an additional $5 spent on groceries feels like a lot. Or, sometimes investors may take an unnecessary loan from a bank to avoid dipping into savings, even if it means losing money. When it comes to investing, mental accounting may put investors at serious risk, and can cause them to avoid proven, sophisticated tools such as Monte Carlo simulations, multi-asset investing, or even basic diversification.

A simple change you can make today

If the idea of tackling behavioral economics sounds too daunting, here’s a simple way you can positively impact your coaching conversations with your clients right now, today, in the next ten minutes: Remove the negative behavioral triggers in your own office.

Dr. John E. Grable, the director of the Financial Planning Performance Laboratory at the University of Georgia, said, “An advisor’s office environment is a projection of the person providing the service.” So, what about your office? What about your office lobby? Does the TV there work for you, instead of against you? Is the financial news crawler at the bottom of the Bloomberg channel encouraging your clients to panic, or to stay the course? Turn it off. Change the channel. Remove the TV altogether.

How about your magazines? Sometimes, the front page of Barrons can give the most stalwart financial professional a panic attack. Is it triggering the same reaction in your clients? Then why is it there? A selection of National Geographics or travel magazines might be a better choice. Make sure your reading material helps to put your clients in a better mental place as they wait to meet with you.

What about your office interior? Does your office create a comfortable—even therapeutic—environment? Have you minimized barriers, such as desks, for more open and more conversational engagements? Does the personality of the office reflect you and your team? Does it show your family? Does it show your credentials? Can clients see what your interests are? Your clients want to know and trust you. Part of establishing that knowability and trust requires you showing them a little bit of your life outside of the office. They want to know that your interests, activities and passions reflects values that they both relate to and respect. Creating a calm, comfortable, relatable office environment is a powerful way to help set the stage for good conversations.

The bottom line

In the formula of advisor value, B is for the behavioral mistakes investors typically make. The good news is that you, the advisor, can have a huge impact on correcting this behavior. Doing so can have an equally huge impact on your clients’ investment outcomes. In fact, addressing the investment behavior of your clients may be the greatest value you provide.

To learn more about the 2019 Value of an Advisor Study, click here.

*Source: Investments & Wealth Monitor, May/June 2017, p. 5