Demystifying private equity valuations

Executive summary:

- Most private equity managers rely on three common approaches to valuation: publicly traded comps, transaction comps, and discounted cash flow models.

- During significant market-moving events, private equity managers tend to be more conservative with their valuations. This typically leads to lower levels of volatility when compared to public equities.

- Although many institutional investors must evaluate private-equity performance versus a benchmark on a quarterly or monthly basis, we believe it's also critical to take a long-term view.

Private markets have long been viewed by institutional investors as a key component of a well-diversified portfolio. The benefits of these strategies are clear: long-term outperformance over public markets, with increasingly important diversification benefits as the universe of publicly traded stocks continues to shrink and performance becomes increasingly concentrated to a handful of mega-cap tech companies. For investors that can afford to sacrifice some liquidity, private equity funds make sense as part of a long-term strategic asset allocation.

While investors tend to assess private equity funds through the lens of alpha generation and diversification, an additional advantage that often goes unnoticed is reduced volatility. The smoothed returns of illiquid investments can easily be written off as being a function of these investments being valued on a quarterly, rather than daily, basis. However, this is not the only factor at play. The methodologies by which private equity funds are valued play a role in their observed volatility, and it’s important for investors to understand the differences in valuation policies between liquid and illiquid funds to properly assess their impact on a portfolio.

How do private valuation methodologies differ from public ones?

Liquid funds are valued based on observable market prices, which can be driven by a combination of both fundamentals and investor sentiment, which may include market trends or recent news about a given company. On the other hand, private equity investments cannot rely on market prices and must use a variety of inputs to derive a fair market value. While different private equity managers may use varying valuation methods, most rely on three common approaches: publicly traded comps, transaction comps, and discounted cash flow models.

The public comp method involves taking observed valuation metrics of comparable publicly listed companies, such as P/E (price-to-earnings) ratios, and applying them to the earnings of a private company to derive an implied valuation. Transaction comps take a similar approach but use the purchase price multiples of recent private transactions of similar companies. Discounted cash flow models project future earnings for a company and apply a discount rate to calculate a present value. In most cases, managers use some type of weighted average of these three methodologies to value their companies. As a result, the values are rooted more in fundamentals and less in market sentiment than public company valuations.

Why is private equity typically less volatile?

What we’ve observed in practice is that when significant market-moving events cause large swings in public stock prices, private equity managers tend to be more conservative with their valuations, taking a slower and more measured approach to writing assets down in a down-market, but also in writing them up in a bull market. This tendency is further exacerbated by the inherent lag in the reporting of private equity funds. Given the number of inputs that go into valuing illiquid assets, as well as procedural hurdles such as annual audits and third-party assessments, valuations are typically not finalised for 45-60 days after quarter-end. This is not considered to be an issue under normal market conditions but can draw scrutiny during periods of volatility.

A notable example is during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Businesses started to feel the effects of the pandemic in March 2020, and public markets were quick to adjust valuations based on the perceived risks. However, the drop in revenues was only partially felt for the Q1 reporting period, so the full effect of the pandemic was not felt in private market valuations until Q2 financials were released, which did not occur until August or September of 2020 for most funds.

Private equity: A smoother ride than public equity?

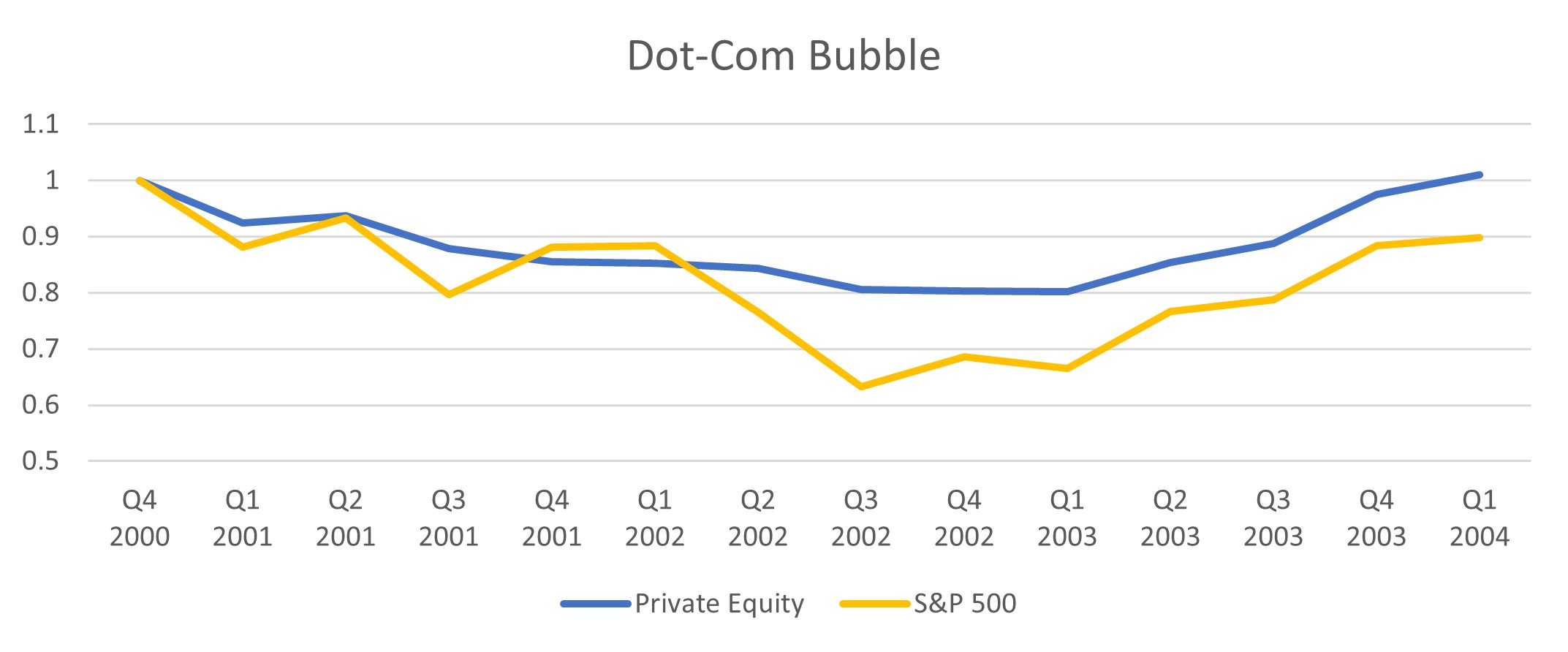

To understand how this impacts returns in today’s market, we can look at how both public and private markets performed in previous cycles. During the dot-com bubble in the early 2000s, private equity funds (measured by Pitchbook’s private equity peer universe) declined in value by 20% from the end of 2000 to their low point in March 2003. It took a year for those funds to fully recover their value, gaining 26% over the following 12 months. During that same time period, the S&P 500 Total Return Index fell by 34% from peak to trough, and then proceeded to gain 35%, displaying noticeably more extreme valuation adjustments than private equity.1

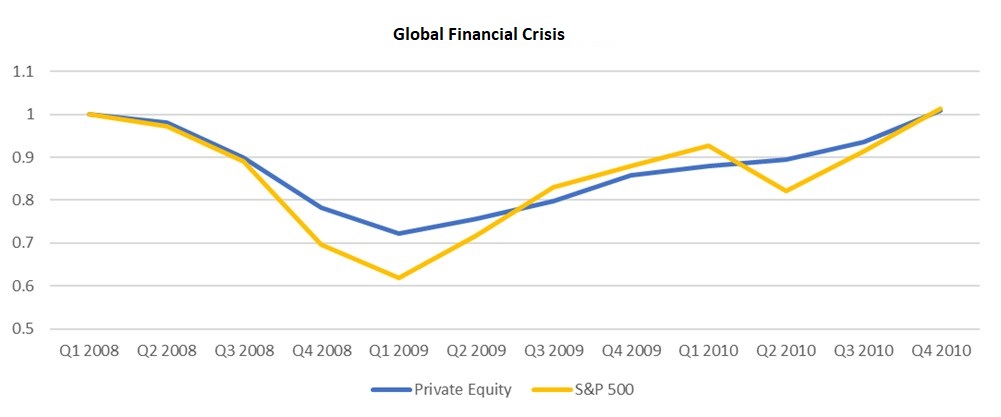

A similar situation played out on during the Global Financial Crisis, though on a larger scale. Private equity funds fell by 28% from March 2008 to March 2009, and took until December 2010 to regain their value following a 40% gain. Meanwhile, the S&P 500 lost 38% during that initial period and then rallied by 64%, fully recouping its losses in roughly the same time frame.

These events demonstrate the importance of taking a long-term view when evaluating the performance of private markets investments, particularly during times of market volatility. When public markets hit what was at the time an all-time peak in November 2021, they proceeded to lose 24% of their value over the next nine months before seeing a 22% gain across the following 12 months. Over that same span private equity funds, lost just 3% before increasing by just 9%.

To an investor looking at short term results, it would appear that liquid stocks were the better investment over the last year or so. But this masks the fact that public equities were regaining lost value, while private equity took a more conservative approach to valuations in the face of economic uncertainty.

The bottom line

The key takeaway from this analysis is the importance of applying the right approach to evaluating the performance of private investments. Many institutional investors must evaluate performance versus a benchmark on a quarterly or monthly basis. However, it’s also important to view those results in the context of long-term performance. The most common metrics used to evaluate private equity performance are since-inception Internal Rate of Return (IRR) and Multiple of Invested Capital (MOIC). Since private investments are largely illiquid and can take a decade or more to realize their true value, these metrics are more aligned with their investment objectives and can paint a better picture of their true performance.

1 Performance sourced from Pitchbook for private equity and Bloomberg for the S&P 500 Total Return Index.

Any opinion expressed is that of Russell Investments, is not a statement of fact, is subject to change and does not constitute investment advice.