Power tool: Why private markets are no longer niche

Bad news: The low-return environment doesn’t seem to be going anywhere anytime soon. Good news: Investing in private markets, done correctly, can help.

The private markets category can be a powerful investment tool for overcoming low returns. But it demands greater levels of risk management at the total-portfolio level. It’s not a tool for the inexperienced or unskilled and demands a deep level of both sophistication and proven experience. That said, the numbers show that many investors are adding PM to their toolbox. The potential value is there, but just how do you maximise and manage the power?

Private markets demand is high. Why?

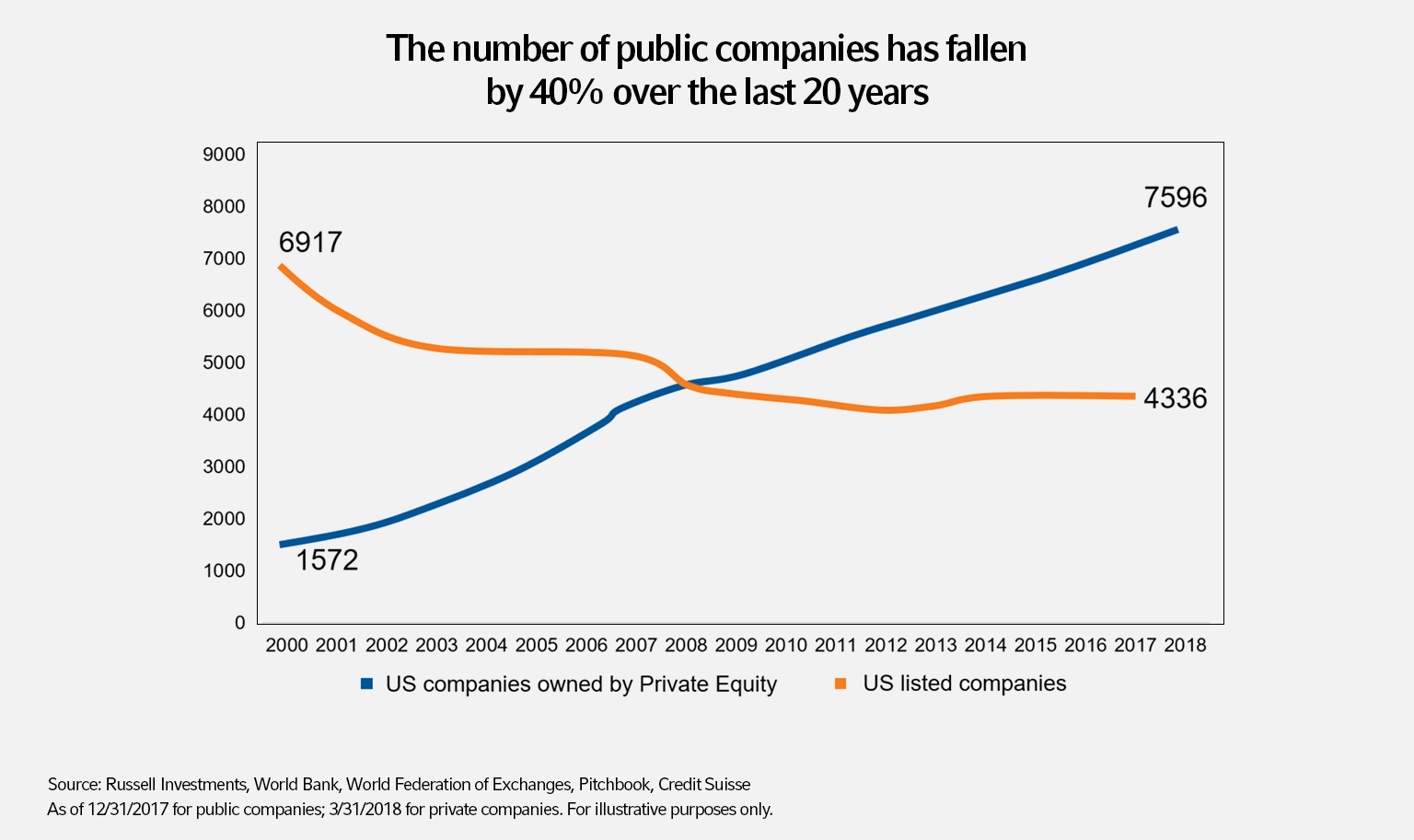

It makes sense that demand for private market investing has increased over the last ten-plus years. For corporations, the desire to either go public or remain public has been stunted by regulators. Post Global-Financial Crisis (GFC), the regulatory environment for public companies has taken a steep upward trajectory. This accelerated level of regulatory scrutiny has had a significant dampening effect on IPOs.

A similar or greater increase in regulations has impacted the banking industry, which has helped to spur a growth in private credit. In fact, according to Preqin, private debt, which was at $848 billion at the end of 2020, is expected to grow to $1.46 trillion by the end of 2025 - an annual growth rate of 11.4%.1

On the equity side, there has been an increased focus on corporations’ short-term results, shared in the form of quarterly earnings. This short-term focus can create significant challenges when it comes to a corporation implementing a long-term strategy. Many CEOs or boards are finding this level of public scrutiny too onerous and are either deciding to put off that IPO or revert from a listed to a private status.

In contrast, the private equity ownership model typically provides longer time horizons and more engaged board members, relative to public-company boards. The boards of private equity companies also take a more active role, because they’re not just board members - they are owners. That engagement can help drive value creation.

From the investor side, private market growth makes sense for two primary reasons: access to the total investable universe and the potential for greater returns. The reality is that equity investors who only invest in listed companies are only getting access to a fraction of the investable universe and are missing out on both diversity and excess-return opportunities.

It’s important to note that underlying public market indices are becoming more concentrated. The five largest stocks in the S&P500 account for approximately 20% of the index’s total market cap, further limiting exposure to the entire investable public-and-private universe.

In addition, there are specific market segments that are simply harder to reach via listed companies. As an example, listed infrastructure indices are often highly concentrated in a few sectors such as utilities, power generation, and oil and gas equipment and services. Expanding the opportunity set to unlisted infrastructure may bring improved diversification as well as exposure to attractive sectors, such as renewables, social infrastructure, and data infrastructure - all of which we believe are harder to gain access to via public markets.

Another key consideration is that the companies that plan to go public now tend to stay private significantly longer. According to Hamilton Lane, in 1999, new companies tended to stay private 4.5 years before IPO. By 2020, that private portion of the life cycle grew to 12 years.2 And that private period may be when a substantial portion of their value creation occurs. For example, Uber and Airbnb are two of the largest, most disruptive tech IPOS and they waited 10 and 12 years, respectively, before they went public. If investors wanted to enjoy the benefit of those disruptions, they would have had to invest during the private portions of the companies’ life cycles.

Click image to enlarge

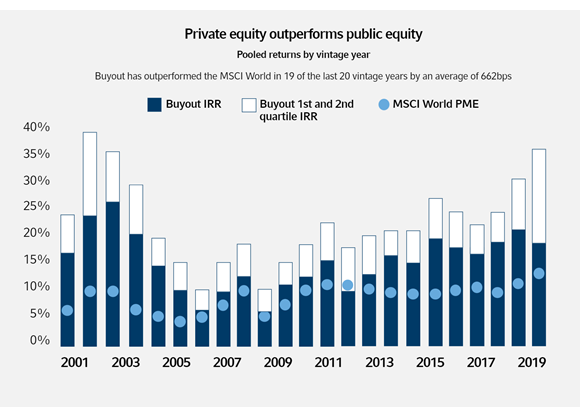

Private markets offer greater return potential

Just how powerful of a power tool are private markets? As the chart above shows, private equity has tended to outperform public equity by a significant margin. As shown here, buyout, net of fees, has outperformed the MSCI World Index in 19 of the last 20 vintage years by an average of 662 basis points. When you hear the objection of higher fees for private markets - as much as 200 basis points higher - keep that 662 number in mind. And the private credit story is similar. According to Hamilton Lane, private credit has outperformed its public counterpart in 19 of the last 20 vintages by an average of 479 basis points.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Hamilton Lane, Bloomberg. January 2021

And when it comes to reducing volatility and protecting funded status, private markets have also demonstrated resilience during market downturns. Consider this fact: Developed market buyout and private credit have never had negative returns over any five-year period, based on data from 1995 to 2020, according to Hamilton Lane.3

The outperformance of private equities makes sense, because private markets have more valuation levers to pull, in the form of three factors:

- Acquisition - Proprietary general-partner (GP) networks can generate new opportunities from which to select investments and can leverage size, industry expertise and complexity. They can also negotiate to optimise deal terms and have access to privileged, non-public information

- Business transformation – PE owners can implement operational improvements, such as cost reduction and talent upgrades, as well as strategic initiatives, such as acquisitions or new product launches.

- Exit – With a long-term investment horizon, GPs can exit at a time of their choosing to maximise value. And they have multiple exit options, including IPOs, strategic buyers, or private equity sponsors.

Does all this mean that private markets always outperform or always earn their higher fees? Definitely not. We believe private market success is highly dependent on skilled active management. In other words, to get the outperformance shown above depends on access to the top-performing PM managers. With traditional equities, active management outperformance tends to depend on a manager’s ability to pick better stocks. That’s also true when it comes to private equities, but a great deal of PM outperformance also depends on access, specifically access to deal-flow and to information.

Deal-flow access deserves a blunt conversation. If a firm only has a small amount invested in private markets, no general partner is calling them first with deal opportunities. At best, they’ll get overflow. Compare that to a firm with $30 billion in privates. An elite firm like that is highly likely to be on the first-call list. Logic then follows that getting the best opportunities requires that level of access.

What might be less obvious is what we like to call the information advantage. Think of it this way: With listed companies, regulations require that everyone gets access to beneficial information at the same time, to avoid insider trading. With a private company, those same kinds of information may exist: They also may be announcing a new acquisition or product launch, but not everyone has access to that information. This creates the potential for an information advantage and more potential for investment alpha, because the information is not democratically distributed. The same can be true with private credit, when privately negotiated loans, with proprietary covenants, terms, or creative structure, can also create information advantages. And who gets that information? Those with access.

The issues (and advantages) of illiquidity

Perhaps the most common objection to private markets is the perceived burden of illiquidity. But one reason we believe private markets outperform is because of a clear advantage that only comes with less liquid assets. Because stock in a listed company is liquid, its shares can be sold at any time by any investor who owns a share. That means that the price of that stock is determined by the actions of all the shareholders. If a large number of shareholders decide to sell their holdings, the value of my own shares are likely to fall, whether I want them to or not. Private equity operates very differently. A small group of decision-makers have the ability to wait for an optimum time to sell - when the value is high. This ability to control the time of sale is at the core of what we call the illiquidity risk premium.

And while private equity and private credit investments are indeed less liquid, investors tend to get their initial investments back sooner than is often believed. In our experience at Russell Investments, a typical PE fund has a 10-year lifespan, but most tend to distribute capital throughout the life of the fund and most investors typically receive back their committed capital by year seven. Private credit funds tend to pay out even faster, with invested capital typically returned by year five. In addition, a skilled partner can help investors optimise toward specific liquidity or income needs.

The bottom line

The reason the private markets category is receiving so much attention is because it is too powerful of a tool not to consider. It’s a mistake to call it niche anymore. But as private markets investing becomes more mainstream, it’s also a mistake to ignore the complexity. Be sure to work with a solutions provider who takes a total-portfolio approach. And be sure to work with one who knows how to maximise the power of this powerful tool.

Any opinion expressed is that of Russell Investments, is not a statement of fact, is subject to change and does not constitute investment advice.

1 https://www.preqin.com/Portals/0/Documents/About/press-release/2020/Nov/FoA-AUM-Nov-20.pdf?ver=2020-11-09-134721-620

2 https://www.hamiltonlane.com/en-us/insight/case-for-private-markets-inve

3 https://www.hamiltonlane.com/CMSPages/GetAmazonFile.aspx?path=~\hamiltonlane\files\86\8607497d-3a97-44d4-aa0a-62a551b201eb.pdf&hash=32e213f73d91d7bff2156e26eebcdb8b2a187168a997cdcc658751e430094ade"">