The bond market in unprecedented times: Strategies for the road ahead

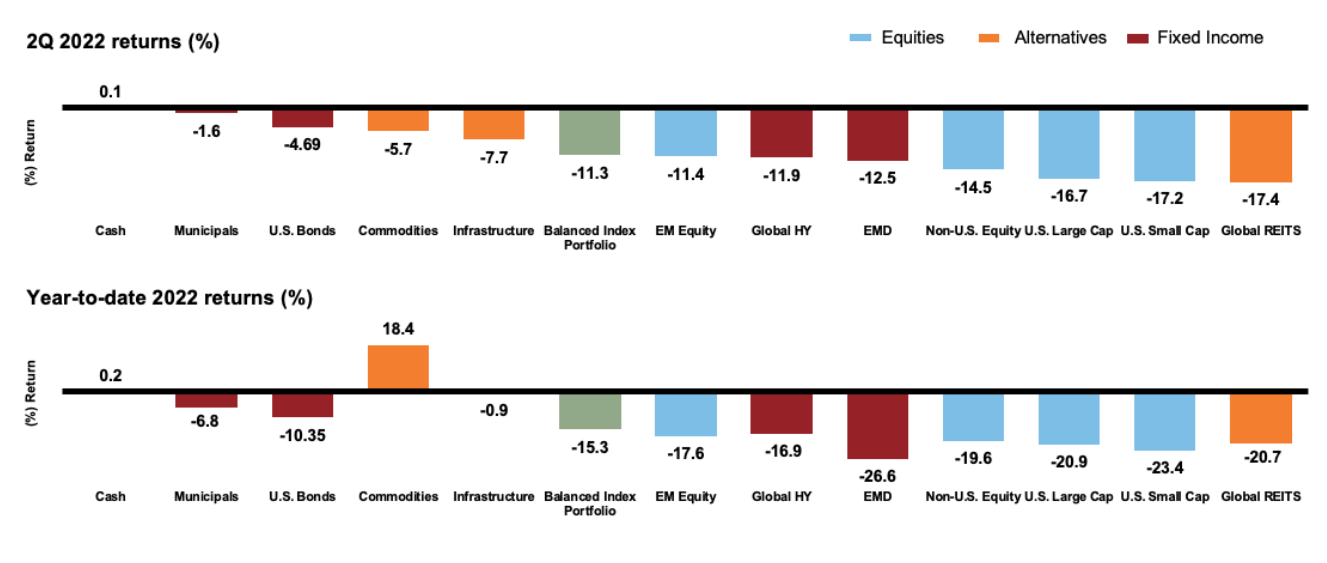

It's no new news that it's been a very challenging environment in fixed income year-to-date, particularly with the U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed) trying to maintain the balancing act between inflation and recession. In the second quarter, we've seen double-digit negative returns across the fixed income landscape. Emerging market debt has struggled, but global high yield was also down 12%. We've seen U.S. bonds down just under 5% for the quarter and over 10% for the year.

Capital markets returns

2Q2022 vs. YTD 2022

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: U.S. Small Cap: Russell 2000® Index; U.S. Large Cap: Russell 1000® Index; Global: MSCI World Net Index; Non-U.S.: MSCI EAFE Net Index; Infrastructure: S&P Global Infrastructure Index; Global High Yield: Bloomberg Global High Yield Index; Global REITs: FTSE EPRA/NAREIT Developed Index; Municipals: Bloomberg Municipal Index, Cash: FTSE Treasury Bill 3-Month Index: EM Equity: MSCI Emerging Markets Index; U.S. Bonds: Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index; EMD: JPM EMBI Plus Bond Index; Commodities: Bloomberg Commodities Index Total Return; Balanced Index: 5% U.S. Small Cap, 15% U.S. Large Cap, 10% Global, 12% Non-U.S., 4% Infrastructure, 5% Global High Yield 4%, Global REITs, 0% Cash, 6% EM Equity, 30% U.S. Bonds, 5% EMD and 4% Commodities. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly.

Institutional investors have been asking: What's the future hold for fixed income?

To answer that question, we invited two leading fixed income authorities to weigh in:

| Michelle Russell-Dowe Global Head of Securities Products & Asset-Based Finance at Schroders Capital |

John Bellows Portfolio Manager at |

Please note: The answers to the questions have been edited for readability and length.

Albert Jalso: What's your outlook for Fed policy for the next 12 months?

Michelle Russell-Dowe: One of the biggest challenges for the Fed, in giving up their dual mission between employment and inflation and choosing to focus on just inflation, is they have a set of numbers they have to look at and they have to figure out, when is enough? What is a neutral Fed funds rate? For us, that is somewhere between three and four percent.

John Bellows: I think Michelle is right. It's a wide range--three to four percent. You could drive a truck through that range. There's just a lot of uncertainty here. In some sense, it was straightforward for the Fed to go from zero to two-and-a-half. It's much harder, however, to do the next 150 basis points, because now you're somewhere in that range that Michelle is talking about. And so I think the natural thing for the Fed to do is to proceed a little bit more carefully with the next 150 basis points than they did with the first 250.

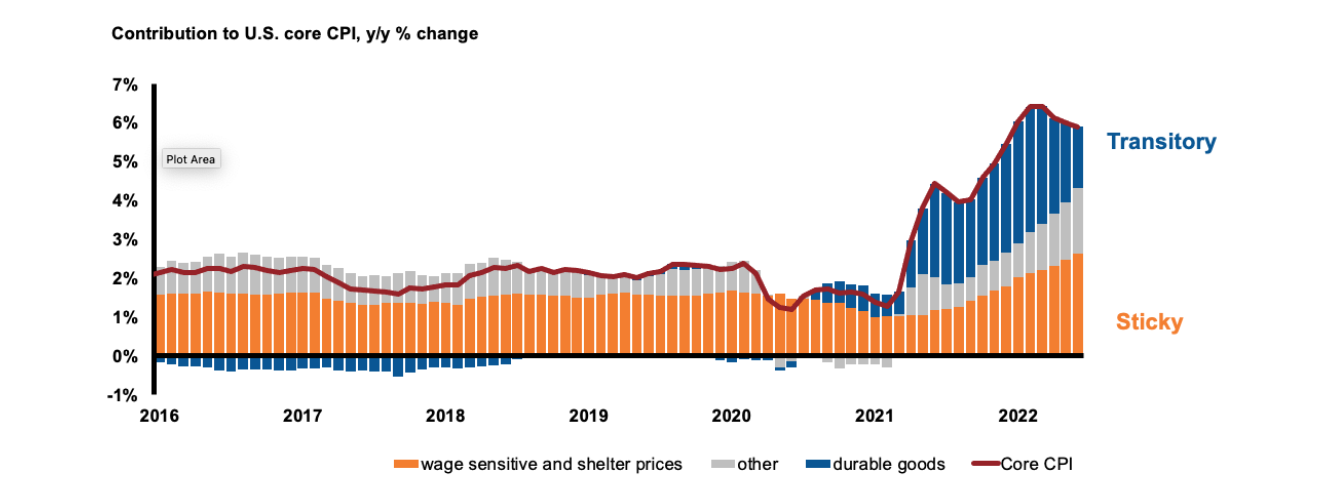

Inflation: Sticky component has broadened

How aggressive will the Federal Reserve be to restore price stability?

(Click image to enlarge)

Source: Refinitiv Eikon/Russell Investments, July 13, 2022

Albert: Duration is a hot topic, particularly as it involves portfolio positioning and how managers are thinking of that in terms of strategy. Michelle, when you think about portfolio positioning and where the Fed is going to go, and inflation, how are thinking about duration?

Michelle: It's like John said. It was easier over the last six months than it will be now.

I'm very neutral at this point, but that's been a change after feeling like rates were a bit of a one-way train for some time. People might have thought I was a little bit kooky at the beginning of the year when I said the US 10-Year Treasury yield could be 3.5%. But that's roughly where we are now and it feels like a pretty fair level, given longer-term inflation expectations.

John: I think Michelle's right. You need to be a little bit thoughtful about where we sit on valuations and where we sit on risks from here. On both valuations and risks we're more constructive than it sounds like Michelle is. I think the valuations are a little bit generous, and they've got a lot of Fed priced in. And I think the risks are probably to the downside in terms of growth.

Albert: John, can I put you on the spot here? How would you be positioning in terms of overall portfolio duration?

John: We are overweight duration. We think that at these levels, it does have some value, given how we assess the risks. I do want to emphasize that we have that position (as a hedge) against an overweight in risk assets.

Albert: For corporate bonds on the investment-grade side of things, we've seen spreads tick 160. And on high yield they've touched over 600. I think history has shown that, more often than not, when they hit those levels, spreads continue to widen beyond that. How are you thinking about adding risk in this environment?

John: You started the question with the right observation, which is, usually when we get to these levels we go wider. My response would be this is anything but a usual environment. I'm skeptical of historic comparisons for that reason. I think this is an unprecedented period and we need to approach it as such. I think there's an alternative [view], which is that we do get that moderation in inflation, the Fed is able to proceed a little bit more cautiously and we can get through the following period without a deep recession. Growth slows, and that's okay, but we don't have a wave of corporate defaults. In that scenario, not only do I think spreads don't go wider. I think there's a lot of value here in spreads.

Michelle: I think also though that the answer can be very different on this one, depending on the time period. If your mandate or your investment needs to be a source of liquidity, my caution would be that I think you have to be very careful about knowing where your liquidity is and making sure that you have that. Because the technicals in the near-term could be very different. If you have funds that are going to provide first-year liquidity sourcing for your clients, the answer might be very different in how you'd apportion risk than if you have something that's much longer-term. That historical comparison, again, is key and could be very different than what people expect. We saw at the beginning of COVID that liquidity was so bad you couldn't even sell an off-the-run Treasury easily. That's the context that I want to put on this: You have to care about different things depending on what liquidity you need. If your fixed income is a source of liquidity, you had better be very careful about how that's invested today.

Albert: Michelle, what areas of investing are you shying away from?

Michelle: It all depends on what the purpose of the instrument is. I seem to be a bit more sensitive to the potential for recession risk than what John's view says, but I agree with John in that I don't think using history is a good precedent, given how so many unprecedented things have occurred. That means being careful about things that don't have history or are bit fringy or are sensitive to the increased financing costs in a way that we haven't seen. So looking at things that have floating-rate financing—they would be inherently more sensitive to the increase in those costs, including things like leveraged loans. The cost of that financing to those companies has gone up materially.

Then there's the non-qualifying mortgage market. It would be unfair to categorize it as the new subprime, because mortgage lending has changed tremendously over the last decade-and-a half. I just think we have untested product with untested borrowers in some of those more fringy, esoteric areas. Being fringy or down-in-quality or [proceeding] with less data is probably not the best option today.

Albert: John, How are you thinking about what you like, what you don't like and what for you is up in quality? I mean, some folks might think that loans are up in quality.

John: You're absolutely right. There were a lot of inflows in the loan funds in the first half of the year, with a lot of people looking for that floating rate exposure. Some of that was due to the unique environment when yields are going up. We'll see what the second half brings, but I think there's a good chance they won't be going up as much as they were in the first half. You see some demand for floating rate securities come off a little bit. And that could be a little bit of a headwind if you don't have those inflows into loan funds. Loans right now have kind of the same value arguments as a high-yield bond does.

Albert: Are you allocating to loans or increasing your exposure to those?

John: We have not. Our increases over the last three months have been in investment-grade and in AAA-rated structures. We're not selling loans, either. I don't think it's a place where you would increase allocations right now, but given where prices are, we'd be reluctant to sell as well. The place where we have reduced a little bit of risk has been in emerging market debt. If we can get through this period without a major global contraction, there's value there, but I don't think it's perhaps as good of a risk right now in portfolios as higher-quality United States corporate bonds.

Albert: Paul Volcker, former Chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve, took the Fed funds rate to 20 percent in 1981, basically saying, I'm going to kill inflation. Why is this time different?

John: Volcker was forced to do that after a 15-year period of inappropriate Fed policies, where the damage was so severe in terms of Fed credibility and inflation that a dramatic response was required. Contrast that with what we're talking about today, where we have not seen the same erosion of Fed credibility. As a consequence, the response that will be required will be quite a bit less. I'll re-emphasize that I think this environment is unique. A lot of what's going on right now is just the aftermath of a pandemic that's disrupted the housing market, the auto market, the goods market and the labor market. A lot of these things are going to be addressed just by putting distance between us and the pandemic.

Michelle: In addition to what was done by the Fed, we're talking about an $8 trillion balance sheet that was also dumped into the market. I agree really with John again: History is not going to serve as a great comparison because of so many different conditions that that are persistent today. We're at the endpoint of a 40-year decline in rates. We have a consumer that's strong at a time when demand is high and influenced by shortages. We have shifts on how people view climate and some of the implications of things like ESG that are plural-inflationary. We have people looking to come into housing and household formations at 50-year highs. The last time we've seen a pandemic at a time when we were hiking rates was 1921. My grandmother happens to have been born in that year and she's still alive. I tried to ask her. She wasn't paying attention back then. But it's an unusual set of circumstances. I think most of the asset managers out there—I would guess including John—are attendant to the fact that you could have a wide range of outcomes. It's very difficult to predict.

Albert: Thank you very much Michelle and John for your insights. We look forward to continuing this conversation in the months ahead.