Will Australian housing drag the economy into a recession?

Economic growth in Australia is going to slow down significantly. However, the buffer that households have put in place should mean that recession risk is not as elevated as other countries around the world. We also believe the rate rises made by the RBA will be less than market expectations given the economic data is already showing signs of slowing, and that Australian government bonds offer attractive valuation.

There has been a growing drumbeat about the precarious position of the Australian housing market, given the aggressive interest rate increases from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). Housing prices have certainly dropped, with the national aggregate down close to 10% since April 2022. In addition, a large proportion of households who fixed their mortgages in 2020 and 2021 are yet to feel the pinch of higher rates. However, this will quickly shift from April, as these loans start to expire. Whilst we expect this to lead to a significant slowing in the economy throughout 2023, we believe it will not lead to a recession in Australia.

How have other developed economies fared?

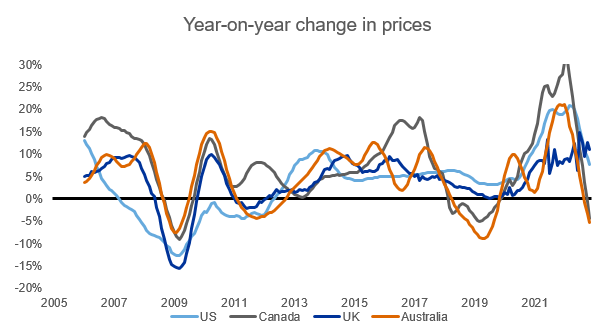

Before digging into the Australian experience, it’s worth highlighting the housing markets of other developed economies. Below shows the 12-month change in housing prices for the U.S., Canada, U.K. and Australia. Canada and Australia have seen the biggest declines, while the U.S. and U.K. market have held up reasonably well.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, 14 February 2023

One of the main reasons for the variation in house prices is the difference in mortgage structures. In the U.S., it is very common to get a 30-year fixed rate. In comparison, a variable (or floating) rate is much more common in Canada and Australia. This is important, as homeowners in Canada and Australia who are on a variable rate may sell due to the financial pressure in rate hiking cycles. Whilst for homeowners in the U.S., they are less impacted.

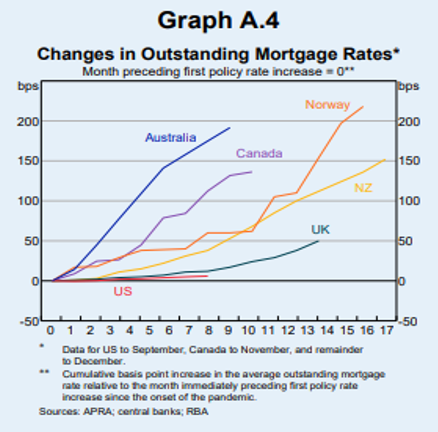

The chart below shows the change in interest rate on outstanding mortgages. Whilst the U.S. has seen larger interest rate changes than Australia, the flow through to mortgage rates is virtually non-existent.

Click image to enlarge

Source: RBA Financial Stability Review, 6 October 2022

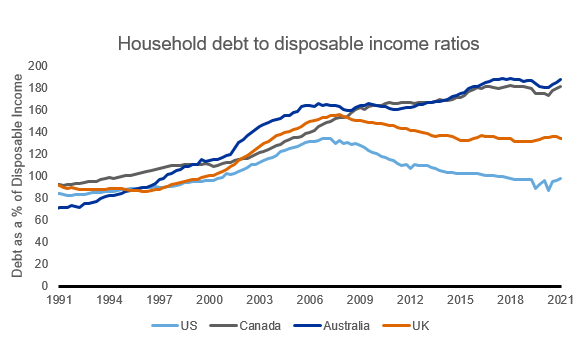

Unlike the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), we do not believe the housing market globally presents a big risk to the economy. The key reason for this is that the household balance sheets in the U.S. (and many other countries) look quite healthy. Essentially, households deleveraged after the GFC and have only just started to borrow again in the last 2 years – some of which was for cars and houses, as well as credit cards in the face of high inflation.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, 14 February 2023

Drawdowns and negative equity in Australia

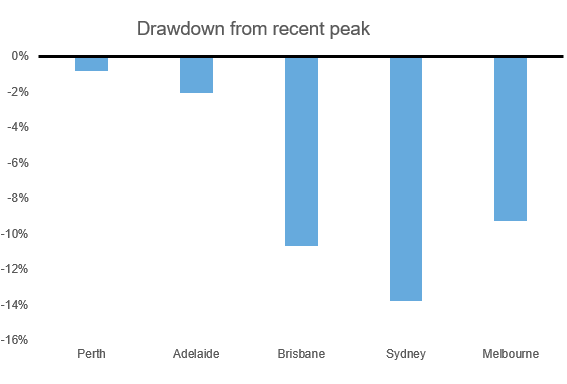

Now if we look at the Australian housing market, a lot of the drawdown has been focused on the east coast markets. Sydney prices have fallen close to 14% from the peak, while Melbourne and Brisbane are close to 10% lower. Despite these declines, it’s important to note that house prices in Australia are only now back to the levels seen in 2021.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, 25 February 2023

Australia’s household debt profile is very different to the U.S., with very high levels of debt observed (as seen in the chart earlier). Additionally, we are about to see a significant number of fixed rate mortgages that were set at around 2% roll off to variable rate mortgages that are closer to 5% or above. This dynamic will become more apparent in April, with the RBA estimating that 60% of borrowers are going to face a 40% increase in their mortgage repayment. This will be a material drag on Australian household discretionary spending. However, a large proportion of households have prepared themselves. More than a third of borrowers have accrued more than two years of repayments in a form of an offset or redraw account, according to the RBA’s securitisation data set.

The big risk for the Australian economy is if we begin to see larger amount of loans in negative equity – that is, where the amount of the loan is greater than the value of the house. So far, it is estimated that around 0.5% of loans are in negative equity. If house prices were to fall another 10% from here, the RBA have estimated that around 1% of loans would be in negative equity – which is manageable on an economy-wide basis. If prices were to fall 20% further, that number would rise to 4% of loans in negative equity, and that would prove quite a challenge for the economy.

The bottom line

We believe that the Australian housing market might face some more weakness, whilst the RBA continue to raise rates. However, this shouldn’t pose a significant risk to the economy.

Economic growth in Australia is going to slow down significantly. As a result, The buffer that households have put in place should mean that recession risk is not as elevated as other countries around the world. We also believe the rate rises made by the RBA will be less than market expectations given the economic data is already showing signs of slowing, and that Australian government bonds offer attractive valuation.