Four ESG trends for institutional investors

ESG dominated global headlines in 2022. The War in Europe resulted in an energy crisis that added an additional layer of complexity to an already challenging energy transition, only one example of a growing infusion of social considerations into the focus on climate. We witnessed polarisation of views in the U.S., with some states blacklisting asset managers following climate action. The year ended with global conferences on climate change in Egypt (COP27) and biodiversity in Canada (COP15). The former included an unexpected breakthrough on ‘loss and damage’, or financial support from rich nations to compensate poorer ones for climate change related loss and damage, but there was disappointment elsewhere.

Where to from here? As we kick start 2023, we reflect on the key ESG trends institutional investors need to be aware of for the year ahead.

Trend #1: Steady pace of new ESG regulation and disclosure requirements set to continue globally

One of the main drivers of increased ESG disclosure amongst investors globally has been the pace of regulatory guidance and enforcement. So far, Europe has led the way with its Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) with the UK set to follow with the Sustainable Disclosure Requirements (SDR). As with SFDR, the UK’s SDR (which is currently still in consultation) is a package of measures aimed at clamping down on greenwashing. Regulators in Australia and the Asia Pacific region also appear to be focusing regulation on greenwashing concerns, with the Australian Securities & Investments Commission (ASIC) taking an especially close focus. Across the Atlantic, the Department of Labor in the U.S. released a final rule clarifying that U.S. retirement plans may consider financially material ESG factors. This followed years of uncertainty after the Trump-era rule had a chilling effect on U.S. pensions.

Global climate regulations will draw on TCFD

Large UK pension schemes (>£1bn) are now required to report in line with the Taskforce on Climate related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), a voluntary set of recommendations which has become part of the regulatory framework in many jurisdictions1. The TCFD recommendations, organised around the four pillars of Governance, Strategy, Risk Management, and Metrics & Targets, are a comprehensive roadmap that investors can use to build a climate risk management programme. Indeed, the International Sustainability Standards Board, which was established at COP26 to set a global standard for climate reporting, is using the TCFD as its baseline. We expect more and more investors across the globe to use the TCFD as a framework to identify, assess, and manage climate risk within their total portfolio.

Trend #2: Focus on climate becomes more socially conscious

While climate change has been a focus for many years now, we are increasingly seeing it referenced alongside social considerations – part of an ongoing erosion of the original “E”, “S” and “G” pillars as distinct silos. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and resulting energy crisis brought this concept to the forefront for many investors: how do we make trade-offs between energy security and climate transition?

Discussion around how to create a just and equitable transition is another example of the integration of climate and social factors which is becoming especially mainstream in Europe. In other regions, the discussion is no less relevant, but likely to go under a different name. For example, in Australia and the United States, coal mining is still an important source of employment in some communities. How are employees being retrained? Ignoring these questions has led to political flashpoints and entrenchment dampening political appetite for speedy transitions. Increasingly, investors are recognising that these two pillars go hand-in-hand.

Increased focus on biodiversity loss

Protecting biodiversity is another example of how environmental and social objectives cannot be siloed but rather must be integrated to achieve outcomes in the real world. Consider an archetypical example: an individual landowner, struggling to feed his family, clears forest on his land to make way for more profitable cattle. This isn’t a one-off case. Many of the most important deforestation prone carbon sinks are in regions that financially cannot afford to save their forests, meanwhile the rest of the world cannot afford to lose them. Like many biodiversity challenges, it is a classic agency problem. The question ahead of us in 2023 and beyond is how can we, as market participants, reduce these market failures?

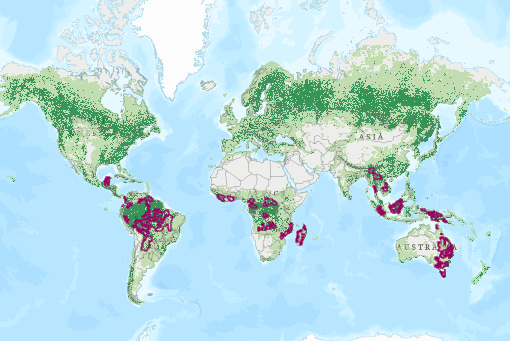

WWF’s Deforestation “Fronts”: Areas of significantly increasing deforestation (red)

Source: WWF

Work is already underway to improve disclosure around biodiversity loss and risks, led largely by the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures, but true incorporation into financial markets is a long way off. In addition, a group of institutional investors recently announced the formation of Nature Action 100 – a new global engagement initiative which focuses on investors driving urgent action on the nature-related risks and dependencies in the companies they own.

Those advancements aside, incentivising people on the ground to minimise biodiversity loss will require new markets, such as carbon credits. Participants are rightfully sceptical, but this doesn’t change the fundamental tenant that these markets will be needed to solve challenges at the intersection of “E” & “S”. In 2023, we eagerly watch for the continued evolution of carbon markets, and other new ideas for reducing externalities, with a pragmatism for human considerations involved.

Trend #3: Growth in investment options to implement ESG beliefs

We have witnessed a rapid expansion of ESG solutions in recent years as a result of evolving regulatory requirements, growth in net-zero commitments, and greater awareness of how ESG issues can impact returns. Our research on manager solutions has significantly expanded over recent years in both the public and private space to include these new opportunities. As an example, the number of global equity strategies in our research universe has grown from 40, three years ago, to about 160 today. The spectrum of opportunity ranges from solutions offering exclusions and negative screening all the way to more thematic and impact strategies. This range of available opportunities means that investors need to be clear about their financial and sustainable objectives in order to find the most suitable opportunity. The risk of greenwashing also means that investors need to have a clear process of assessing these solutions to ensure it delivers in line with expectations.

Sustainability focused public equity funds, for example, are offering an increasingly diverse set of themes and investment approaches including:

- Strategies that invest in companies with practices that protect and leverage natural capital through trends like the circular economy, resource efficiency, and zero waste.

- Strategies that invest in companies with differentiated and impactful social practices that allow them to retain and nurture talent resulting in superior IP and stronger competitive advantages.

- Strategies that invest in companies with a proven and superior track record of stewardship of capital. These companies are typically able to sustain higher levels of profitability for longer.

Active stewardship: A lever to enhance long-term sustainable value

By way of definition, active stewardship is the use of the shareholder rights and ownership to influence the behaviour of issuers. It is also viewed as one of the key levers by which investors can promote good practices on material issues that may protect and enhance long-term sustainable value creation.

Our 2022 ESG Manager Survey findings and investment work tell us that investors are increasing their focus on ESG matters and thinking about how to implement this into their engagement and proxy voting activities. While governance remains at the top of the agenda for investors, climate risk has risen significantly as a key priority. We expect this trend to continue in 2023. Further insights on active ownership can be found in our recent blog 2022 ESG survey deep dive: Active ownership review.

Trend #4: Data and transparency move further into the spotlight

In the year ahead, we expect greater scrutiny on ESG data quality. Take carbon emissions as an example. Investors are increasingly reporting carbon emissions associated with portfolio constituents, known as portfolio carbon footprinting. Often, a portfolio carbon metric is accompanied with a measure of what percent of the portfolio has emission data, also referred to as data coverage. A data point for say an equity portfolio with 98% coverage was more reliable than one for a fixed income portfolio based on 20% coverage.

Increasingly, this coverage information is being broken down further, to what percent of the portfolio has data actually reported by the company. If an investor subscribes to MSCI ESG research, Trucost S&P, ISS, Sustainalytics or any number of other carbon data providers, coverage for a global index or portfolio can be very high, but this is not necessarily because companies are reporting the data. Instead, the data provider applies estimation algorithms to fill in missing data based on a company’s industry, activities, and location.

With the emergence of the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF), the concept of a data quality score is gaining prominence. In order of decreasing quality this looks at what percent of the carbon is verified, reported, estimated or not available at all. This concept enriches the potential avenues for making progress since it is no longer exclusively about reducing a headline portfolio carbon footprint figure – which may have been based largely on estimates – but rather improving the quality of the data itself.

Scope 3 data comes of age. But is it really ready for the spotlight?

The market has been talking about Scope 3 emissions for a long time, so what is changing in 2023? Several frameworks listed 2023 as the phase-in year for Scope 3 emissions. This includes PCAF, Principal Adverse Impacts, and the UK’s Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) climate rules2.

Investors in Europe have been dutifully getting ready for this collective Scope 3 launch party, so presumably that means companies got the message and started reporting Scope 3 emissions? Of course not, that would be too easy! Corporate disclosure of Scope 3 emissions is still woefully low and inconsistent.

Even where companies are reporting, the precise categories included in Scope 3 disclosures vary widely, making the data incomparable. For example, the agricultural company Cargill reports very high Scope 3 emissions compared to oil pipeline companies. Taken at face value, this suggests Cargill has the larger value chain emissions. On closer inspection, the oil pipelines have only reported certain categories of upstream Scope 3, and no downstream emissions. One can immediately see how acting on Scope 3 data at this stage is likely to penalise companies like Cargill who are the first to disclose. Instead, investors still need to rely on estimations to get figures that are apples to apples. In 2023, we will continue to push for more corporate disclosure while emphasising that company-reported Scope 3 emissions at the portfolio-level are not a reliable measure just yet, and fly counter to the “data quality” concept introduced previously.

The bottom line

It’s clear to see, irrespective of location, there are ESG requirements either already in place or coming into force. These will cause implications for how you invest now and where returns are generated in the future. The good news – if you have ESG beliefs you want to implement, there are a wide range of tools and frameworks available to meet the needs of your investment portfolio. However, a word of caution, while data quality and reporting transparency have moved into the spotlight, investors must still be mindful of the wide use of estimations and comparing like-for-like on certain metrics.

1 Including the European Union, UK, Singapore, Canada, New Zealand, Japan, Brazil, Hong Kong, Switzerland and South Africa.

2 In the case of the DWP’s TCFD rules, scope 3 emissions are required after the first year.