B is for behavior coaching. Perhaps the most important role advisors play.

The GameStop saga earlier this year provided an eye-opening realization of just how easy it is for the average investor to trade stocks on their own—and just how prone they are to follow a trend. Indeed, a surge of small investors using the Robinhood trading app triggered a massive short squeeze that drove GameStop stock 400% higher at one point before it began to fall. 1 Many of those investors—who shared information through an online stock-trading forum—first gained, then lost millions.

Most of us would find it difficult to live through that kind of frenzy. Indeed, some of the investors who lost money in the GameStop roller-coaster likely bought their shares as they were going up, then may have sold those shares when the retreat was in full swing. But of course, they may not have been working with an advisor.

At Russell Investments, we believe in the value of advisors. We believe investors who steer clear of trading apps and instead listen to an advisor’s trusted counsel, have a much better chance of avoiding the pitfalls that investors working on their own frequently fall into.

That’s why we produce our annual Value of Advisor study which clearly shows that the value-add an advisor brings to their clients is well above their typical fee. And we believe communicating that value is more important than ever.

This simple formula helps communicate that value:

A+B+C+P+T

We’ll be discussing the various contributions that advisors make to their clients’ investment journey in a series of blog posts diving deeper into our 2021 study. The first blog post was on the value of actively rebalancing—the A in the formula above—especially during volatile times such as last year.

This post will look at the B in our formula: behavioral mistakes that investors typically make.

During our decades of working in this industry, we’ve heard that most advisors spend the bulk of their time trying to minimize their clients’ behavioral mistakes, especially when markets become volatile. We like to hear this, because our value of an advisor study shows that taking on the role of behavioral coach may be the most important role a financial advisor can play. Most advisors know far too well that investors don’t always do what they should. Instead, their behavior is sometimes directly opposed to what is in their own best interests.

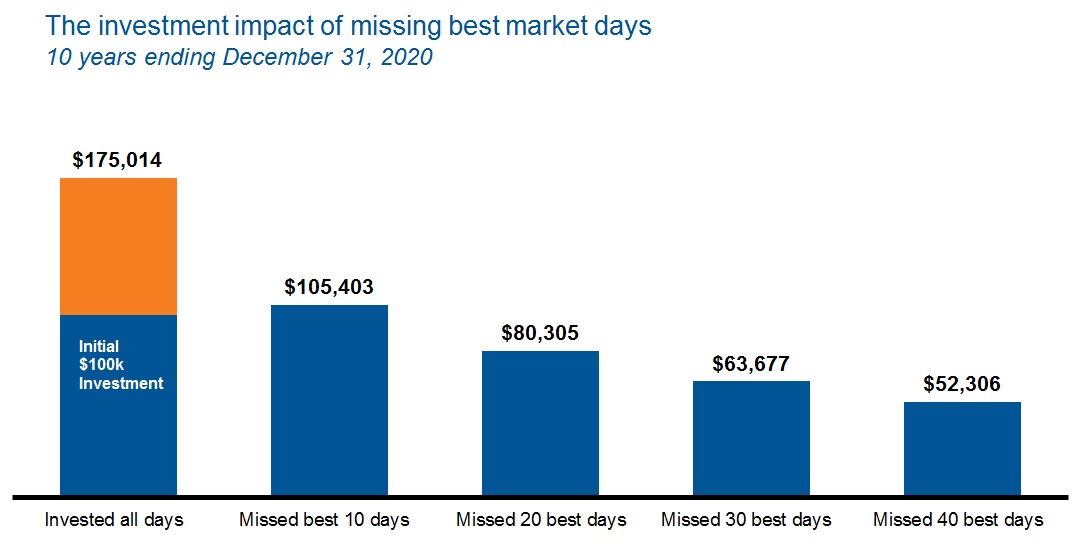

We don’t need a speculative frenzy such as that surrounding the GameStop shares this year to understand how badly the average human wants to get in on a good thing, and how easily we are spooked by falling prices. We saw it in early 2020, when the COVID pandemic first hit and the markets shuddered. In the month of March alone, $15.6 billion was pulled out of equities. What happened in the following months? Equities recovered steadily throughout the remainder of the year, and the S&P/TSX Composite Index closed 5.6% higher by the end of 2020. Even bond markets rose in the year.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Russell Investments. Morningstar. Timeline of Events Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic: https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/timeline/covid-19-pandemic. Data from January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020. Canadian Equity= S&P/TSX Composite Index; Canadian Fixed Income=FTSE/TMX Canada Universe Index. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Circles represent return from market high point to low point. WHO=World Health Organization.

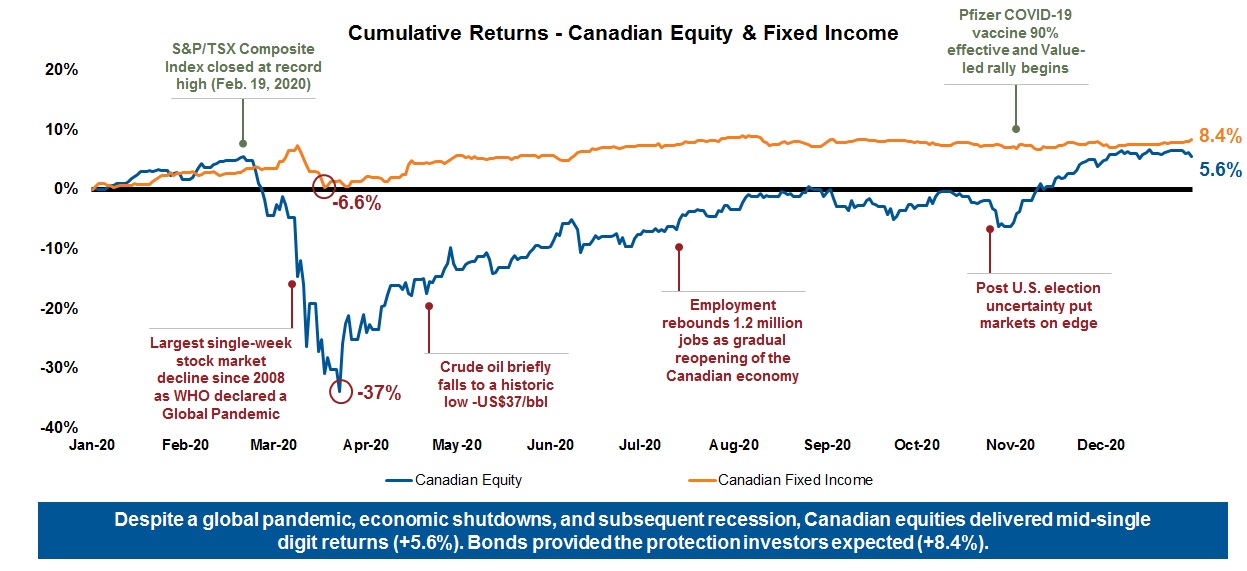

Click image to enlarge

Source: Morningstar. In CAD. Returns based on S&P/TSX Composite Index, for 10-year period ending December 31, 2020. For illustrative purposes only. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly.

Click here for underlying data for determining best days: https://russellinvestments.com/ca/resources/financial-professionals/value-of-advisor/

The cycle of investor emotions

We all know that 2020 was a wild ride and while this year has been less volatile, there are still a lot of uncertainties surrounding the pace of vaccinations, the emergence of different strains of the virus, how widespread the return to the traditional workplace will be and which economic sectors will rebound quickly and which will not.

Investors, like all humans, look for patterns, even when they shouldn’t. And sometimes, looking for patterns can get investors into trouble, especially when their pattern-chasing inclinations cause them to make the wrong decisions at the wrong times. As we saw with the GameStop saga, they also tend to follow the herd. The herd tends to leave the market when it has begun to fall—meaning investors tend to sell low. And the herd tends to enter the market when it is rising—meaning investors tend to buy high.

This happens because people have real anxiety when it comes to money. It is not so much the actual physical bill that causes the anxiety, it is about what happens when things go wrong. Sometimes that anxiety causes people either to make a bad decision or no decision at all. We often find the biggest detriment to an investment’s return is not the actual investment, it is the investor’s behavior with that investment, especially when volatile markets make them anxious. An advisor who can keep their clients from succumbing to their human instincts to buy high and sell low can be incredibly valuable.

What does this all mean? Clients pay your fee because they are looking for someone to help them reach their goals. One of the key ways they can reach their goals is to stick with their plan during turbulent times. You can be the person who has the courage to fight your clients’ greatest nemesis—themselves. Although it may mean having a challenging conversation, an advisor cuts through the noiseand protects the client from making behavioral mistakes they are classically prone to do—like buying GameStop on the way up and selling it on the way down, or selling all their stocks to buy bitcoin, or getting into tech stocks in the late 90s.

Obviously, this investor behavior can hurt investor returns. Practically speaking, if an investor’s personal situation really hasn’t changed, then staying the course and riding through these periods of volatility is the logical course. But that is humanly hard. So what can a good advisor do, since we can’t control the markets? We can control—or at least help control—this very behavior. That means instead of opening an account with a robo-advisor and getting financial advice from Reddit, an investor will have a conversation with his or her advisor where they can coach their clients through these challenging conversations. And that conversation—just that simple conversation—could save them from making a costly mistake.

Behavioral economics: Where finance and psychology meet

Behavioral economics is the academic body of work that recognizes the difference between what human investors should do and what they actually do. This is where traditional finance and economics meet psychology.

One of the key beliefs of behavioral economics is that changing bad investor behavior begins with awareness. Think about how tracking your daily number of steps with a Fitbit can increase the number of steps you walk each day. The power of the Fitbit is the awareness it generates. For your clients, behavioral change begins with personal awareness of their investing behavior—of the investment biases that may be causing their mistakes. Once our clients are aware of these biases, you, the advisor, can be that accountability partner to help them stay on course.

Five common investment biases

Within the science of behavioral economics, there are over 200 identified biases that impact their money decisions.2 Here are the five we consider to be the most common—and the most important for advisors to address.

- Loss aversion – Humans tend to prefer avoiding losses more than acquiring equivalent gains. In other words, the pain of loss is a more powerful force than the gratification of gain. This fear of loss may cause your investor clients to want to sell winning securities too early. And the fear of missing out may cause investors to hold onto losing securities too long.

- Over-confidence – Investors tend to over-estimate or exaggerate their ability and expertise. In other words, they tend to believe they are experts when they are not. Their belief in their ability to time the market, for example, may cause them to trade too often or at the precisely wrong time. Or their belief in their ability to identify opportunities may cause them to risk too much exposure on a perceived hot stock.

- Herding – Humans tend to mimic the actions of the larger group. When the herd tends to sell and pull out of the market, individual investors tend to join in, even if it means selling low. When humans tend to buy, individuals tend to jump on the bandwagon, even if it means buying high.

- Familiarity – Humans tend to prefer what is familiar or well-known. We see this in the way investors tend to overweight their portfolios toward their home countries, even when there might be a recommendation to diversify globally.

- Mental accounting – Investors tend to attach different values to money based on its source or location or based on a gut feeling. This from-the-gut approach to investing may put investors at serious risk, and can cause them to avoid proven, sophisticated tools such as Monte Carlo simulations, multi-asset investing, or even basic diversification.

The bottom line

In the formula of advisor value, B is for the behavioral mistakes investors typically make. This value strikes a significant chord following the upheaval seen last year. The good news is that you, the advisor, can have a huge impact on investor behavior and thereby on investment outcomes. In fact, addressing the investment behavior of your clients may be the greatest value you provide.

To learn more about the 2021 Value of an Advisor Study, click here.