B is for behavioral mistakes: How much value comes from prevention?

There are now so many stock-trading apps that you can find lists ranking the top 10 stocks. Investors now have the ability to buy and sell securities on the phone they keep in their pockets or purses. They can make big moves while they’re at the beach or on the train. Some folks champion that access. Not us.

Imagine that an investor chose to pull out of the market on March 23 this year—when the S&P/TSX Composite Index (representing Canadian stocks) closed at 11,228.50. They would have missed a three-day bounce up to 13,371.20—19%. Think about that: just three days.

What prevented many investors from making a mistake that big? Their advisors.

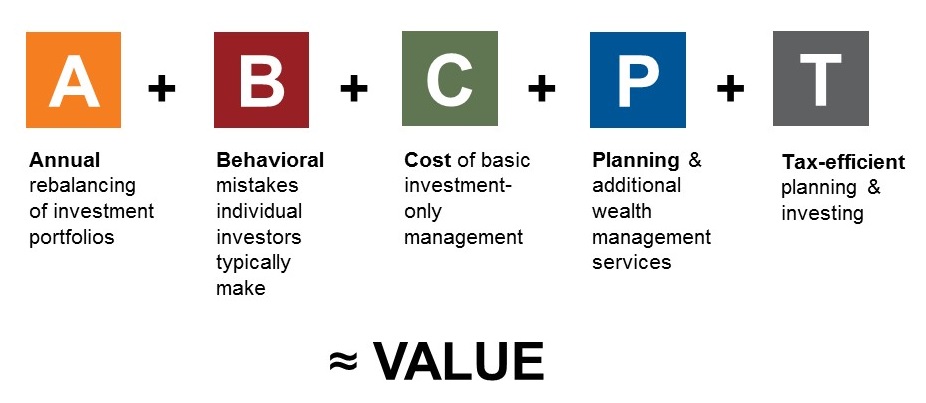

You’ve heard us say it before, but we’re saying it again: Russell Investments believes in the value of advisors. And we believe communicating that value to your clients is more important than ever. That’s why we propose this simple formula:

Value of an Advisor = A+B+C+P+T

Click image to enlarge

In the first blog post in this five-part series, we discussed the value of annual rebalancing. In this post, we’ll tackle the behavioral mistakes that investors typically make and the value advisors provide in helping investors avoid those mistakes.

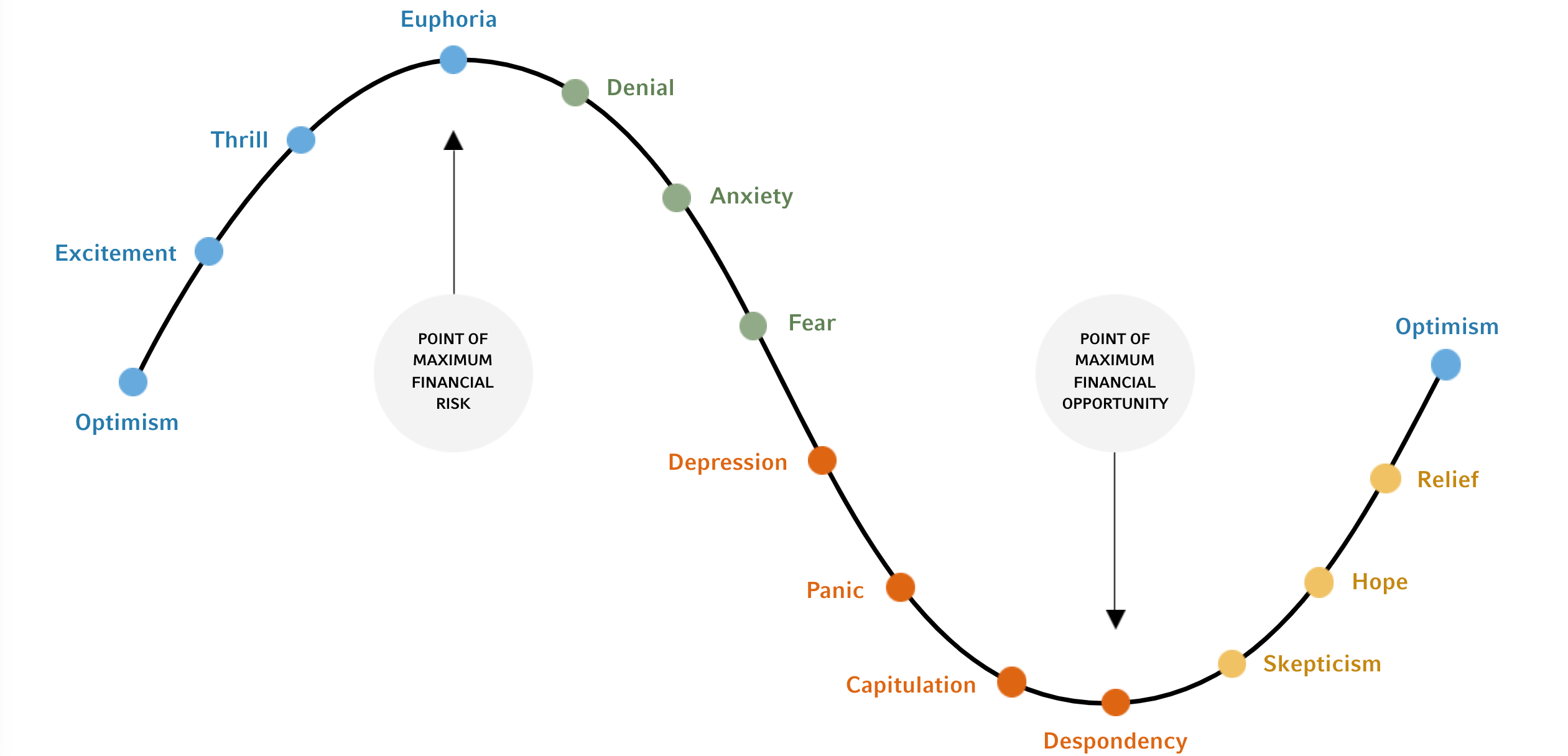

The cycle of investor emotions

We all know that this year has been a wild ride so far, and we’ve heard from advisors that they’ve recently delivered more value in this area than they have for some time.

Investors, like all humans, look for patterns, even when they shouldn’t. And sometimes, looking for patterns can get investors into trouble, especially when their pattern-chasing inclinations cause them to make the wrong decisions at the wrong times. They also tend to follow the herd. Left to their own devices, the investor herd, overall, is inclined to do precisely the wrong thing at exactly the wrong time. The herd tends to leave the market when it is down—meaning investors tend to sell low. And the herd tends to enter the market when it is up—meaning investors tend to buy high.

Obviously, this investor behavior can hurt investor returns. Practically speaking, if an investor’s personal situation really hasn’t changed, then staying the course and riding through these periods of volatility is the logical course. But that is humanly hard. So what can a good advisor do, since we can’t control the markets? We can control—or at least help control—this very behavior. So that, instead of following their gut and pulling out of the market at precisely the wrong time, an investor will have a conversation with his or her advisor. And that conversation—just that simple conversation—could save them from making a costly mistake.

What do some of those advisor-client conversations about the emotions of investing look like? They are interactive, they are transparent. And yes, they’re often emotional. As an advisor, you can’t stop the wave, but you can teach your investors how to surf.

To help support those surfing lessons/conversations, especially in today’s virtual meeting setting, we recently launched a new piece of digital content on our website: The cycle of investor emotions. If you haven’t seen it yet—be sure to check it out!

Click image to enlarge

For illustrative purposes only.

With this interactive chart, advisors can illustrate for their clients that the very point where investors feel the most despondent—where they may have the highest desire to leave the market—may also be the point of maximum financial opportunity. It’s the advisor’s role to coach them through this cycle—and what a cycle it’s been in 2020. We believe having an accountability partner, like a skilled financial advisor, gives the investor a significantly better chance at making good decisions during periods of both emotional and market volatility.

Behavioral economics: Where finance and psychology meet

Behavioral economics is the academic body of work that recognizes the difference between what human investors should do and what they actually do. This is where traditional finance and economics meet psychology.

Click image to enlarge

One of the key beliefs of behavioral economics is that changing bad investor behavior begins with awareness. These may sound like tricky conversation with clients—convincing them that they are not experts—but they don’t have to be. One way we often help increase awareness in presentations—let’s say to a room of 30 people—is to go through some deceptively simple brain teasers and confidence questions like Are you an above average, average or below average driver? The audience experiences first-hand some of their false assumptions, their overconfidence, their biases. They surprise themselves by shouting out the wrong answer to the easy brain teasers, they all raise their hands to indicate they are above-average drivers. Obviously, most people can get the brain teasers right if they take the time to think, and not all of them can be above-average. They just think they are. It’s that unconscious thinking that we as advisors want to get to when making clients aware of their emotionally driven (and hence often flawed) investment rationales.

Five common investment biases

Within the science of behavioral economics, there are more than 200 identified biases that impact their money decisions.1 Here are the five we consider to be the most common—and the most important for advisors to address.

- Loss aversion – Humans tend to prefer avoiding losses more than acquiring equivalent gains. In other words, the pain of loss is a more powerful force than the gratification of gain. This fear of loss may cause your investor clients to want to sell winning securities too early. And the fear of missing out may cause investors to hold onto losing securities too long.

- Over-confidence – Investors tend to over-estimate or exaggerate their ability and expertise. In other words, they tend to believe they are experts when they are not. Their belief in their ability to time the market, for example, may cause them to trade too often or at the precisely wrong time. Or their belief in their ability to identify opportunities may cause them to risk too much exposure on a perceived hot stock.

- Herding – Humans tend to mimic the actions of the larger group. When the herd tends to sell and pull out of the market, individual investors tend to join in, even if it means selling low. When humans tend to buy, individuals tend to jump on the bandwagon, even if it means buying high.

- Familiarity – Humans tend to prefer what is familiar or well-known. We see this in the way investors tend to overweight their portfolios toward their home countries, even when there might be a recommendation to diversify globally.

- Mental accounting – Investors tend to attach different values to money based on its source or location, or based on a gut feeling. This from-the-gut approach to investing may put investors at serious risk, and can cause them to avoid proven, sophisticated tools such as Monte Carlo simulations, multi-asset investing, or even basic diversification.

The bottom line

In the formula of advisor value, B is for the behavioral mistakes investors typically make. This value strikes a significant chord this year, when market volatility has been so stark. The good news is that you, the advisor, can have a huge impact on correcting investor behavior. Doing so can have an equally huge impact on your clients’ investment outcomes. In fact, addressing the investment behavior of your clients may be the greatest value you provide.

To learn more about the 2020 Value of an Advisor Study, click here.

1 Source: Investments & Wealth Monitor, May/June 2017, p. 5