Do we really need to be worried about the U.S. banking sector?

Executive summary:

- U.S. banks have reemerged as a potential pain point for the investment community, as rating agencies recently embarked on a downgrade cycle in the sector.

- There’s no single cause for these bank downgrades, which means this probably should not be taken lightly.

- Similarities to the 1980s Savings and Loan Crisis may mean this is more of a multi-year slog than a single event.

- The macro backdrop may lead to less liquidity in the system, which ultimately creates a drag on the U.S. economy.

Is the banking crisis back?

Months after the messy regional banking crisis in March 2023 that saw four meaningful U.S. bank failures (Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, Credit Suisse, and First Republic), banks have reemerged as a potential pain point for the investment community, as rating agencies recently embarked on a downgrade cycle in the sector.

Moody's acted first on Aug. 7, with a round of 10 credit-rating downgrades that included Commerce Bank, BOK Financial, M&T Bank, Old National Bank, Prosperity Bank, Amarillo National Bank, Webster Financial, Fulton Financial, Pinnacle Financial and Associated Bank. Additionally, they noted that they are reviewing credit ratings of six additional banking institutions including BNY Mellon, Northern Trust, State Street, Cullen/Frost Bankers, Truist Financial and US Bank.

On Aug. 21, S&P Global downgraded the creditworthiness of its own group of five U.S. banks, while putting two others on negative outlook. The agency applied downgrades to The Associated Banc Corp, Comerica Inc., KeyCorp, UMB Financial Corp, and Valley National Bancorp and added River City Bank and S&T Bank to negative-watch.

Reasons for the downgrades?

Interestingly, there is not one overarching cause that applies across the board for these bank downgrades, which underscores the reason this probably should not be taken lightly— despite a sense of calm around these issues in the months between March and August. There are a lot of different and interrelated reasons.

Essentially all U.S. banks are juggling at least one of these five problems, if not several of them:

- High short-term rates and an inverted yield curve – This challenge applies to essentially all U.S. banks, and it creates a difficult operating environment for the banking system overall. At the simplest level, banks borrow money at short-term rates (deposits) and lend money at typically higher, longer-term rates (residential mortgages, consumer loans, business loans, commercial real estate loans). In other words, an inverted yield curve makes for tough sledding in the banking sector. And the longer the curve stays inverted, the more challenging profitability becomes, as loan volumes and net interest margins decline and funding pressures mount.

- Deposit competition and deposit flight – Not only are banks facing challenges making profits on their deposits, due to the increased short rates compared to longer-term lending rates, but they also face stiff competition for those deposit dollars from better yielding alternatives like money market funds, short-term treasuries, certificates of deposit (CDs), and other cash alternatives. Additionally, on the back of the bank failures earlier this year, depositors have grown more cautious about leaving funds in excess of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insured maximums (US$250k per depositor) with the banks.

- Commercial real estate debt – U.S. Banks—and regional banks in particular—tend to be large lenders to commercial real estate projects. These are often the smaller, more localized real estate loans that make up a large proportion of all Commercial Real Estate (CRE) debt. Given the well-known challenges in a post-COVID reality around CRE sectors like office buildings—where hybrid and remote work arrangements are putting pressure on occupancy levels and lease pricing—and the secular decline of brick-and-mortar shopping that is putting pressure on retail properties, these loans could be exposed to losses and defaults. Furthermore, higher interest rates and a tighter lending environment from banks potentially create a vicious cycle, where refinancing options become more difficult for challenged CRE properties. This can exacerbate the issues, as there becomes less flexibility around curing challenged loans.

- Implied losses on securities portfolios – As seen with the Silicon Valley Bank failure, U.S. bank asset portfolios are comprised of meaningful levels of low coupon treasuries and agency MBS securities that were purchased for the Hold-to-Maturity (HTM) bucket of the balance sheet, when interest rates were still very low. As interest rates rose throughout 2022 and 2023, these securities experienced price declines because of the interest-rate effect on their longer durations. Typically, U.S. banks are not required to mark these securities to market in the HTM segment, so in normal times these price declines would not create issues. However, when deposits leave the bank, the institutions are forced to liquidate securities at market prices, which realizes actual losses on the assets.

- Regulatory pressure – As a direct reaction to the securities losses and balance sheet issues noted above, U.S. banks are once again under regulatory scrutiny with respect to the asset-liability mismatch between borrowing at short-dated rates and investing in longer-duration assets, where interest-rate risk poses potential solvency risks. At this stage, proposed regulatory changes have not been finalized, but more mid-sized and regional banks will become susceptible to heightened bank regulation consistent with the money center banks, who have been more intensely scrutinized since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008.

One size issue doesn’t fit all bank downgrades

One observation surrounding the recent wave of bank downgrades is that these issues are impacting a diverse group of U.S. banks. And there is little consensus around the specific banks most at risk. Notice that between the Moody’s downgrades and the S&P downgrades, there is almost no overlap in names. Furthermore, if you go bank by bank and read the rationale for the downgrades, there are quite a variety of concerns cited for each case. Some of the downgrade activity stemmed from profitability challenges around funding costs and declines in lending. Some were more concerned with outsized commercial real estate exposures. And others were more related to regulatory challenges. What this tells us is that this isn’t necessarily just an idiosyncratic issue for certain banks: it’s a broadly challenging operating environment and liquidity issue for banks and the U.S. financial sector overall.

Akin to the GFC or the savings and loan crisis?

Another observation is that the instinct for investors around this challenged environment for banks seems to be to conjure comparisons to the GFC, but the U.S. banking system has de-levered meaningfully since 2008 and these are quite different issues. The current period is more akin to the savings and loan crisis in the early 1980s in certain ways. During that period, banks faced similar challenges from higher deposit rates, stubborn inflation, asset-liability mismatches between short-term deposits and long-duration mortgages, and deposit outflows due to competition from higher rate cash alternatives.

The point in highlighting this is that the savings and loan crisis was less of a big bang catastrophe like what we saw in the GFC and more of a multi-year, ongoing slog. The savings and loan crisis took a different tack and the government tried deregulation to help banks grow out of these problems, which was a very different mistake from today, but many of the challenges remain similar. During that period, more than 2,000 banks wound up failing, albeit in part due to offering higher deposit rates and then investing in riskier assets, which is not the case today. Nevertheless, this operating environment is similarly challenging for banks. These hurdles help explain the heightened eagerness from the investment community for the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) to end its hiking cycle and for yield curves to steepen, before these issues lead to more far-reaching outcomes, like additional bank failures or a credit crunch of some magnitude.

What to make of this downgrade wave

Are we concerned about these downgrades as it relates directly to bank stocks and bank corporate debt? Or is this a bigger picture issue in a macro sense?

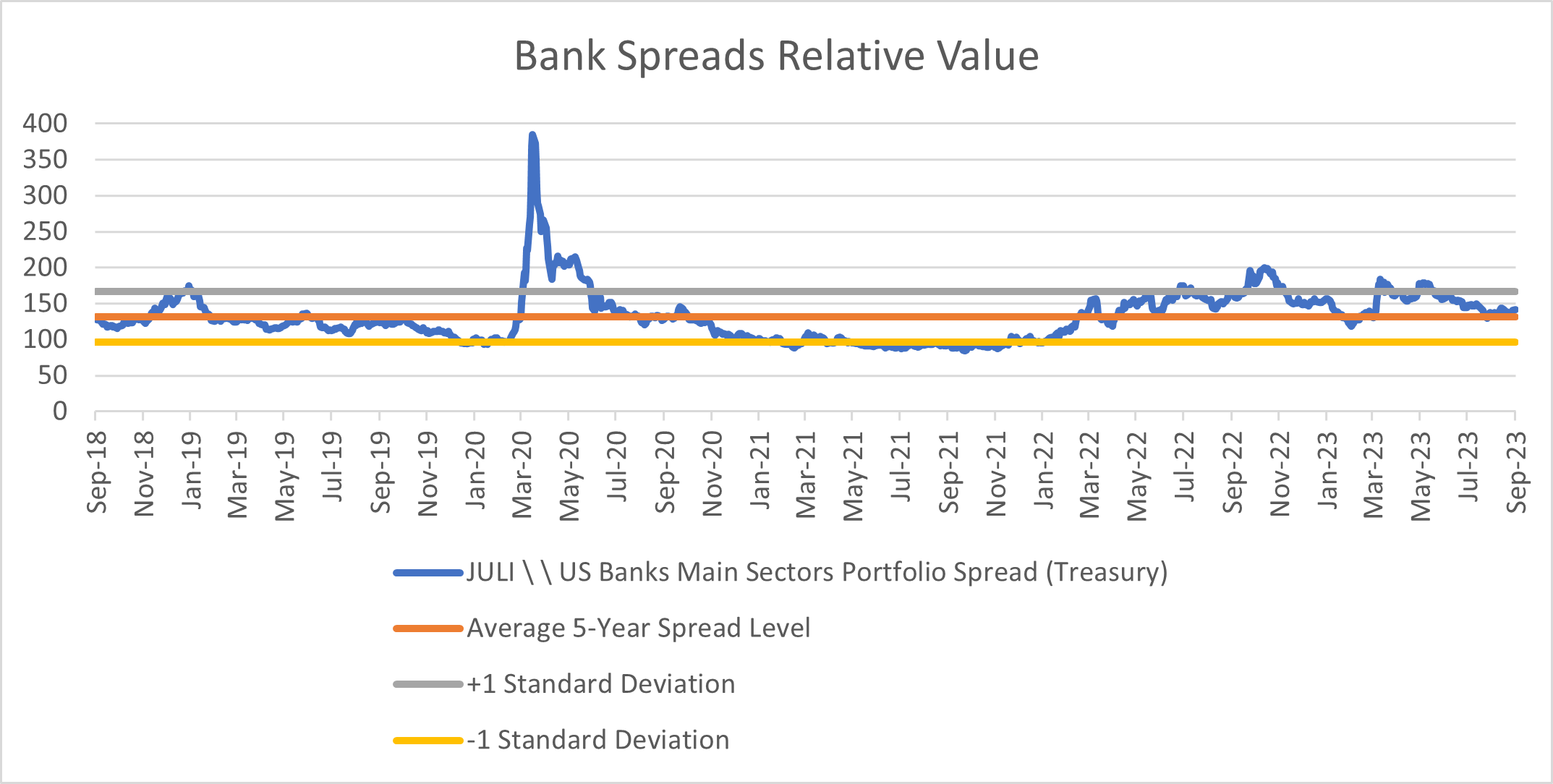

To be clear, despite all the efforts to clean up the U.S. banking system since the GFC, the sector remains quite complex and opaque. Hence, we would not claim to have the expertise to categorically predict which banks will struggle or even which of the issues on our laundry list of challenges will become the most prescient. What we can see is that regional banking stock prices have moved -26%, compared to +16% for the S&P 500 on the year-to-date basis. This reflects a high degree of pain embedded in the bank stock prices. Meanwhile, bank credit spreads sit just wide of five-year average levels, reflecting some heightened credit risk, but not a sign of panic. Both bank stocks and bonds could certainly deteriorate further, but overall, the sector-specific risks seem relatively well-reflected in the markets.

KRE Regional Bank ETF vs S&P 500 Index year-to-date returns

We think the bigger-picture macro backdrop bears monitoring as it relates to the banking system. To be clear, we are not suggesting a systemic banking crisis on the horizon, but this backdrop will lead to less liquidity in the system, which ultimately creates a drag on the economy. These issues will take time to play out. And we still don’t know the full extent of the impact that higher rates will have on the U.S. consumer, commercial real estate prices, deposit activity, bank profitability, or the overall economy. Remember that it takes on average 11 months from the time the yield curve inverts to the time the economy enters recession, and we currently remain well within this range, as inversion occurred in October 2022.

The bottom line

The confluence of challenging factors likely points to a continued retraction in lending activity from banks. And that could ultimately create a drag on both consumer and corporate spending and investment. This comes at a time when the Fed is also pulling back from a decade-plus of unprecedented stimulus and liquidity injections into the economy. This removal of liquidity from the financial system has the potential be a catalyst that finally tips the economy into the elusive recession. And it could create a drag on broader asset prices beyond what we have seen directly reflected in the banking sector.