What is holding back China stimulus?

One of the vexing questions for China watchers has been the lack of stimulus delivered, despite the maintenance of the government’s 5.5% GDP target for 2022 (although there is skepticism around the ability to reach that 5.5%). This is especially puzzling given the lockdowns that occurred during the first half of the year, and the precarious situation of the housing market (which is impacting consumer confidence). It’s possible that some of the spending was delayed by this year’s COVID-19 outbreak itself, as the government’s focus amid rising infections in March and April shifted to keeping the virus contained.

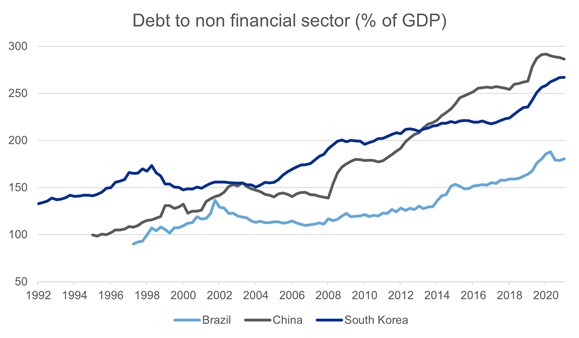

Another suggested reason is that China’s desire to escape the middle-income trap is holding back some of the stimulus. China is already significantly leveraged and has unfavorable demographics—and the combination of these two puts pressure on future growth prospects. This could limit the desire to further add to the debt burden of the government, and the private sector, through fiscal and monetary stimulus.

What is the middle-income trap?

But what exactly is the middle-income trap? It is a reference to the situation where a middle-income country fails to become a higher-income nation. In fact, very few counties have successfully managed the transition from middle to high income, with many economies in Latin America, the Middle East and East Asia struggling to break into higher-income status. The World Bank estimates that of 103 middle-income regions in 1960, only 13 were high-income by 2008.1

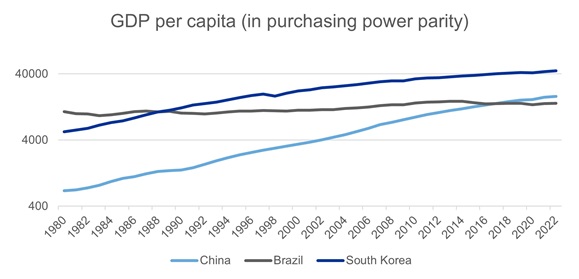

Brazil and South Korea are both good examples of countries that fell into the middle-income trap and managed to break through it. This brings us to the obvious question: is China more like Brazil or South Korea? We believe China is working toward becoming more like South Korea, with its focus on increasing domestic consumption and demand—dual circulation is the vernacular used by Chinese policymakers. China is also climbing the value-add chain through increasingly sophisticated manufacturing. An often-underappreciated development is that China now leads the world in patent applications.2 This is similar to what South Korea did with its technology exports—and something that Brazil failed to do. Case-in-point: To this day, nearly 65% of Brazilian exports are mining and agricultural products.

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, Russell Investments

What role could China’s debt-to-GDP ratio be playing?

Now that we have covered the background, let’s focus on today. As shown in the chart above, China has surpassed Brazil in terms of GDP (gross domestic product) per capita, but is still some way from South Korea. Note that the chart uses a log scale, so each distance on the y-axis represents the same percentage move.

One of the big challenges China faces relative to South Korea is the amount of debt it holds for the level of income. China has a debt-to-GDP ratio of just under 300%, as compared to South Korea, which had a debt-to-GDP ratio of under 150% at a comparable level of economic development. It is important to note that a lot of Chinese corporate debt is actually held by state-owned entities, which have historically had an implicit guarantee from the state. In recent years, there have been some examples of state-owned firms defaulting, but a lot of this debt is held by systemically important institutions in China.

The question now becomes, how important is this consideration at the current juncture? We don’t think that it is driving much of the seeming delay in stimulus announcements. Whilst it is true that Chinese authorities have become more focused on the high levels of debt in recent years, there is a large premium being placed on economic stability and strength over the coming 12 months given the National People’s Congress at the end of the year.

As China reopens, is more stimulus on the way?

Instead, the balancing act of stimulus measures versus COVID-19 prevention has been the challenge. With the nation’s economy now reopening and COVID-19 treatments coming closer to fruition, sluggish consumer sentiment and an elevated youth unemployment rate lead us to believe that the impetus for stimulus is increasing. To date, we have seen further reductions in interest rates and more announcements on infrastructure spending—including a recent report that the government is considering allowing bond sales of US$220 billion to fund local infrastructure projects—but we think more needs to be done on the demand side of the equation. This is why we expect more measures focused on consumption to be announced in coming months.

Additionally, if we are correct in expecting a slowdown in the developed world over the next 12 months, the need for more stimulus will only increase, as Chinese exports are likely to deteriorate.

The bottom line: More stimulus likely, and a complicated outlook for emerging markets

We believe that additional China stimulus should provide support to emerging market (EM) equities, of which China comprises a very large part of the index. The other risk that has been hanging over EM equities has been the pressure on Chinese tech companies from regulators.

We are seeing signs that the regulatory regime is easing gradually, and we expect that the sector will benefit from general easing policies through the second half of 2022. Offsetting this, though, is the fact that EM equities tend to have a high sensitivity to global growth—meaning that an economic slowdown would offset some of the recent positivity. Ultimately, amid this backdrop, we continue to look for dislocation opportunities in EM equities or more attractive valuations.

1 For reference, these were Equatorial Guinea, Greece, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Mauritius, Portugal, Puerto Rico, South Korea, Singapore, Spain and Taiwan.

2 https://www.natlawreview.com/article/china-remains-top-patent-cooperation-treaty-filer-2021