5 reasons why U.S. rate increases are likely to slow in the months ahead

Investors have increasingly become disquieted about the prospect of rising inflation accompanied by higher interest rates. There is logic to such concerns. We believe that the U.S. can attain gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 7% in 2021. If achieved, that would be the fastest pace since 1984. Moreover, in March 2021, the annual inflation rate in the U.S. increased to 2.6%, the most rapid pace of price increases since August 2018.

Robust growth accompanied by higher inflation is traditionally a recipe for higher interest rates. We agree. The rise in the U.S. 10–year Treasury bond yield from 0.50% to a post–pandemic high of 1.75% reflects the improving outlook for growth and inflation. The question becomes: is there more to come?

Never say never, but we believe U.S. long–term rate increases from here will be more gradual, and the U.S. 10–year treasury bond yield to trade between 1.5% to 2.0% through the end of 2021, for several reasons:

- The U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed) has been clear it will look through a temporary spike in inflation due to base–effect comparisons to last year or due to any supply bottlenecks as the economy reopens. Although the Fed's most direct impact is on short–term interest rates, its outlook also serves as an anchor for longer maturities. We believe the Fed will not raise its target rate until late 2023 or early 2024. The market, by contrast, has already priced in a few Fed rate hikes for 2023, which should limit how high rates can get for longer maturities. Moreover, a precondition to liftoff will be slowing the pace of its monthly bond purchases, known as tapering. At the moment, this is not under consideration.

- Market expectations for future U.S. inflation have been rising, but have now reached levels we would judge to be consistent with the Fed’s inflation objectives over the long run. Interestingly, inflation expectation is now higher for the medium–term outlook compared to the longer term. Inflation break–even—or implied inflation, measured as the difference between nominal yield and TIPS (Treasury inflation–protected securities) equivalent—is higher over a five–year term versus 10 years. This inversion of the TIPS curve, which occurs when shorter–term implied inflation exceeds longer–term, suggests inflation concerns are expected to intensify but lessen over time.

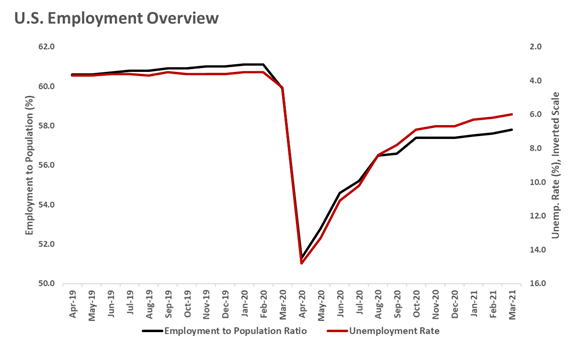

- While the U.S. economy is accelerating, the quarter–to–quarter growth rate will most likely decelerate over the second half of 2021, and the output gap—the difference between actual and potential growth—is not expected to close until sometime in 2022. The U.S. labor market has healed significantly. But the current U.S. unemployment rate of 6% conceals the true health of the labor market. Labor force participation remains depressed, particularly for parents with young children whose schooling has been impacted by COVID. To emphasize this point, the chart below illustrates that the improvement in the employment–to–population ratio has not kept pace with the progress observed in the unemployment rate. A full reopening of the economy will need to absorb this hidden labor market slack as well.

- The search for yield is a global phenomenon. As U.S. rates rose from post–pandemic lows, the higher levels have attracted foreign buyers. If sustained, rising foreign demand would boost the value of U.S. Treasuries and lower their yield.

- The extra compensation—or term premium—that investors demand for owning a longer–term bond relative to rolling over of short–term bonds has normalized higher as well in recent months. Historic fiscal stimulus and historic real GDP growth rates justifies such a move. But at a level of around 50 basis points, this term premium for the US 10–year Treasury bond has shifted back to its average for the period following the Great Financial Crisis of 2008/09.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Refinitiv DataStream, Russell Investments. As of March 2021.

The crucial takeaway is that we expect future interest–rate increases in the U.S. to moderate. This is welcome news for bond investors. While unpleasant from a return perspective, the rise in interest rates improves the outlook for fixed income for two primary reasons:

- Higher interest rates mean total return expectations have improved due to a higher starting yield.

- Critically, higher yields offer more downside protection if equity market volatility was to resurface. A higher starting yield means more room for interest rates to move lower in a risk–off environment, which would boost the total return of fixed income relative to equities.

The bottom line

Ultimately, it comes back to asset allocation. Stocks and bonds both serve a purpose. If interest rates are rising due to an improving growth outlook, well, then equities are likely strengthening, offsetting the negative impact from higher yields on the bond allocation in a balanced portfolio. However, financial markets are inherently volatile, and fixed income performs the critical function of offsetting equity market volatility. Seen through that lens, the rise in rates over the past year doesn't seem all too disconcerting.