Expensive stocks and expensive artwork

By now I’m sure you’ve either heard about or seen on social media that at Art Basel, a banana duct-taped to a wall was sold for $120,000. I personally think that price is totally bananas (pun intended).

Wait…what??

It’s the work of Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, and it’s literally a banana duct-taped to a wall at Art Basel in Miami. It’s titled “Comedian” and sold for $120,000. He made three of the works and, after selling the second for another $120,000, increased the asking price on the third to $150,000. What makes this artwork so unique is that Cattelan literally walked into a supermarket in Miami, bought a banana and taped it to the wall. The dealer declared it to be worth $120,000. And people bought it. Overnight “Comedian” became a media sensation and hundreds of observers lined up to take selfies with the world's most expensive banana. The New York Post put the banana on the front page, with the headline “Art World Gone Mad.”

What is price and what is value?

When I was in college, I started becoming interested in behavioral aspect of personal finance. Admittedly I also forced myself to learn about these topics because a lot of young adults graduate college without even knowing the difference between a stock and a bond. I would write down quotes that made sense to me, but also quotes that I didn’t understand—and knew I had to dig deeper to find the true meaning. This banana story reminds me of a Warren Buffet adage that I wrote down in 2009 when I first entered the industry: Price is what you pay, value is what you get. It implies that price and value are not always one and the same.

Stocks are no different from any other merchandise, yet somehow the expectation is that once you like a stock, you should like it regardless of price. For example, instead of thinking of Caterpillar as a stock, let’s think of it as a nice sweater that catches your eye at the mall. You go to the store, look at the $50 price tag, decide that’s a fair price and buy it. But let’s pretend you went back the next day, and the same sweater was selling for $95. Would you still pay for it? You would probably think twice.

We use this same logic when we buy cars, televisions and houses, but when it comes to stocks we’re supposed to like them at any price? Wrong. The difference between shopping for shares of Caterpillar in the stock market and shopping for a sweater in the mall is that in the market you get a different price every day, allowing you to decide when Caterpillar’s price is a bargain. If we really liked that sweater at the mall, we probably wouldn’t buy it on markup days, and instead purchase it when we see a big sale coming. We should apply the same logic in our stock investments. It’s easy to see why behavioral biases lead to poor investment decisions, especially when markets are rising.

Late-cycle investing: It’s about avoiding emotional mistakes

When I first learned about “Comedian”, I couldn't believe that someone would pay that amount for something so silly. Of course, that’s just my opinion. Obviously the definition of art has changed over time, so who am I to judge? The point I’m making is that whether you’re overpaying for artwork, automobiles, a house or a stock, you could potentially face big losses if you disregard risk, especially today in the second half of a full market cycle.

FOMO (fear of missing out) is the biggest detractor to long-term performance. FOMO has returned with a vengeance after the market’s performance in 2019. Every day there are more articles advising retail investors to disregard risk. The problem is if you let yourself make the emotional mistake of chasing returns, you end up buying high and selling low. We believe that to be a successful investor, you must understand herd mentality and use it to your benefit, which means getting out in front of the herd before you get trampled.

Forward-looking risk management

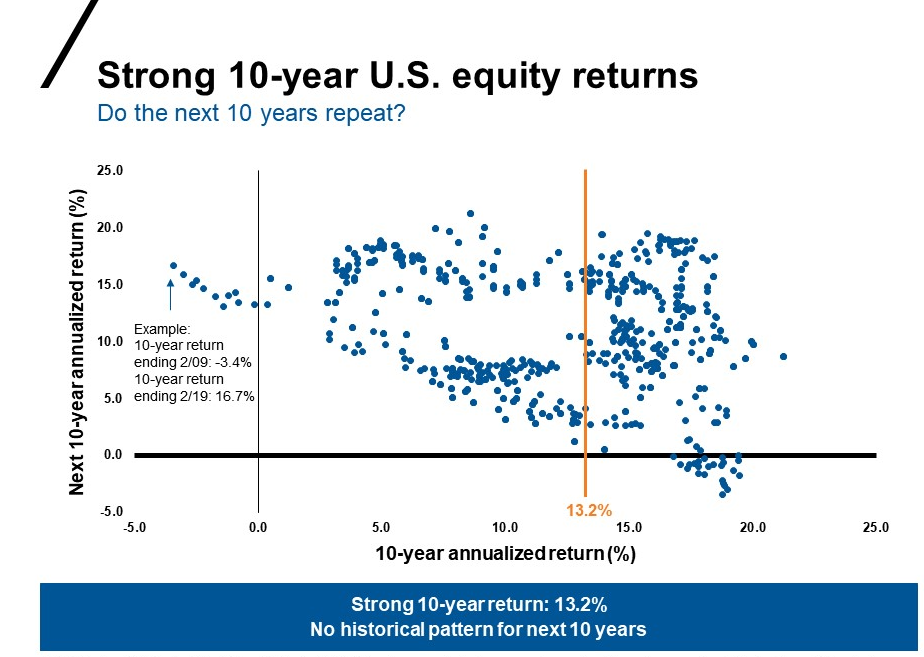

As we begin the new year, we believe it's a great idea to look at your portfolio and see if you need to recalibrate the price you are willing to pay for future investments with their value. When I talk with advisors, I see a very common theme across many client accounts: home-country bias. Undeniably U.S. markets have done exceptionally well over the past 10 years, but it’s prudent to ask will the next 10 years be a repeat? As we’ve stated in our 2020 Global Market Outlook, the challenge of investing late in the cycle is that the upside for equity markets is likely smaller than the downside.

Note: U.S. Equity returns: S&P 500 Index, April 1, 1936 through September 30, 2019. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment.

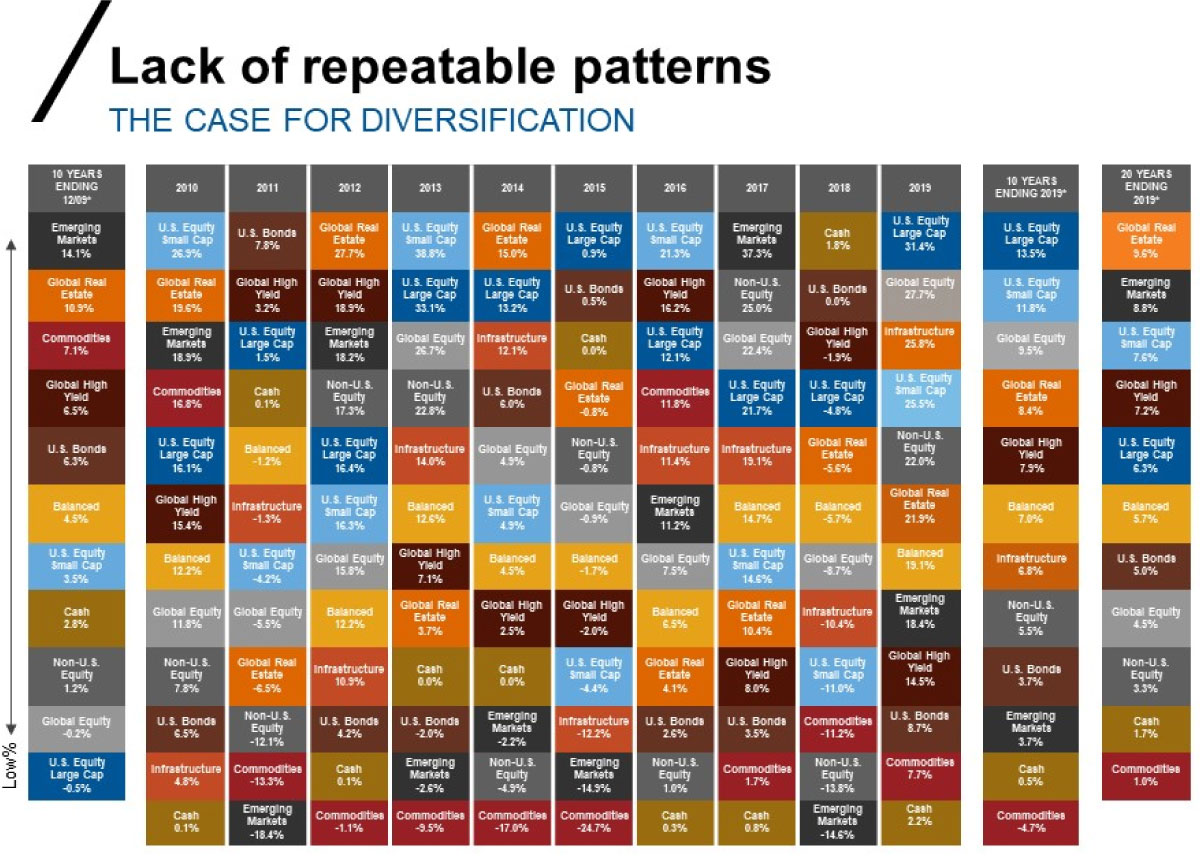

Russell Investments believes in a global multi-asset approach

We believe that having a globally diversified portfolio across various asset classes is one of the smartest strategies to take on risk. Lastly, as we try to manage more market volatility in the future, it’s good to remember that timing the marketsisn’t a strategy. Instead, reducing risk through proper asset allocation is the more prudent strategy to winning the long game, helping to lower volatility while helping to avoid emotional investor behavior.

Click image to enlarge

*Annualized return. Non-U.S. Equity – MSCI EAFE Index; Global Equity – MSCI World Index; Emerging Markets – MSCI Emerging Markets Index; Global Real Estate – FTSE NAREIT All Equity Index (1/1/1995-2/18/2005) & FTSE EPRA/ Developed Index (2/18/2005-12/31/2019); Cash – Bloomberg US Treasury Bill 1-3 Month Index; Global High Yield – Bloomberg Global High Yield Index (1/1/1990-12/31/1997) & BofAML Global High Yield TR Hdg Index(12/31/1997-12/31/2019); Infrastructure – S&P Global Infrastructure Index; U.S. Bonds – Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index; U.S. Equity Large Cap – Russell 1000® Index. Balanced: 30% Russell 3000® Index; 35% Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index; 20% MSCI EAFE Index; 5% MSCI Emerging Markets Index; 5% FTSE EPRA/NAREIT Developed Index; 5% Bloomberg Commodity Index. Please note that this chart is based on past index performance and is not indicative of future results. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Index performance does not include fees and expenses an investor would normally incur when investing in a mutual fund. Diversification and strategic asset allocation do not assure profit or protect against loss in declining markets.

The bottom line

At this moment, the purchasers of the banana probably think it was a perfectly rational decision, and that the price they paid could turn out to be a bargain (but bananas rot, right?). These buyers/speculators are thinking in terms of ego that the price could increase even higher. Hopefully, when it comes to investing, we don’t make the same behavioral mistakes—and the banana holders’ future returns don’t slip up.