Is this time different? Perspective on the growth-vs-value debate

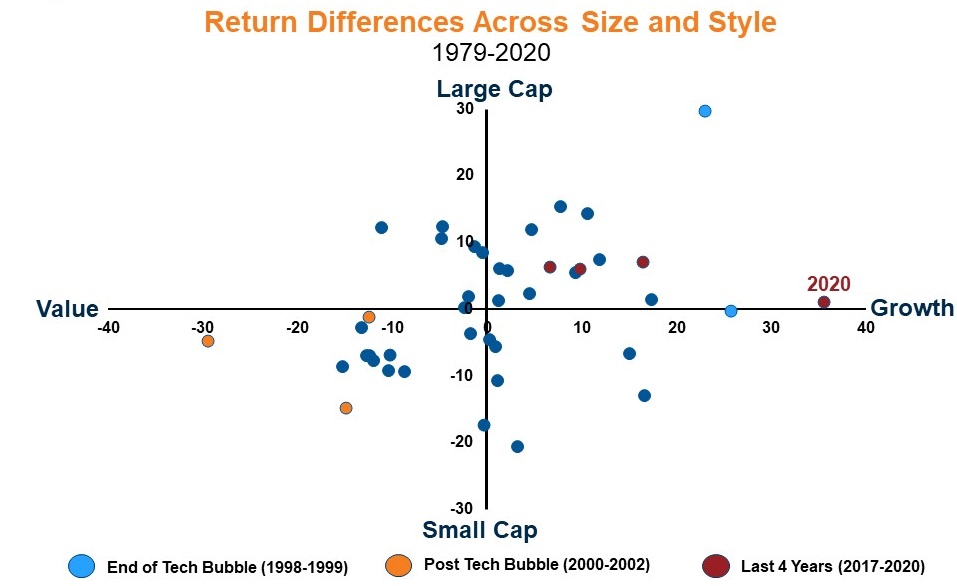

As many investors likely have noticed from their most recent quarterly statements, the U.S. stock market overall has been a great place to be invested over the last 10 years. But there is one segment that has stood out above the rest. According to Morningstar, U.S. large cap growth stocks (as represented by the Russell 1000® Growth Index) have produced a total return of nearly 400% over this time frame—more than double the return of 171% from their large cap value counterparts (as represented by the Russell 1000® Value Index). Returns have been particularly strong in the last four years as shown in the table below.1 In 2020, large cap growth outperformed large cap value by more than 35%, which marked the largest margin of difference between the two in any calendar year.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Morningstar. Large Growth=Russell 1000® Growth Index, Large Value=Russell 1000® Value Index, Small Growth=Russell 2000® Growth Index, Small Value=Russell 2000® Value Index. Indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment.

While growth stocks have been the big winner of late, market leadership historically has rotated so that no single method of investing consistently outperforms. Given the recent multi-year run of narrow market leadership, this could mean it is more important than ever to maintain diversification in your investment approach. Additionally, it is crucial to understand what you own in your portfolio, in order to not be caught off guard when leadership eventually reverses.

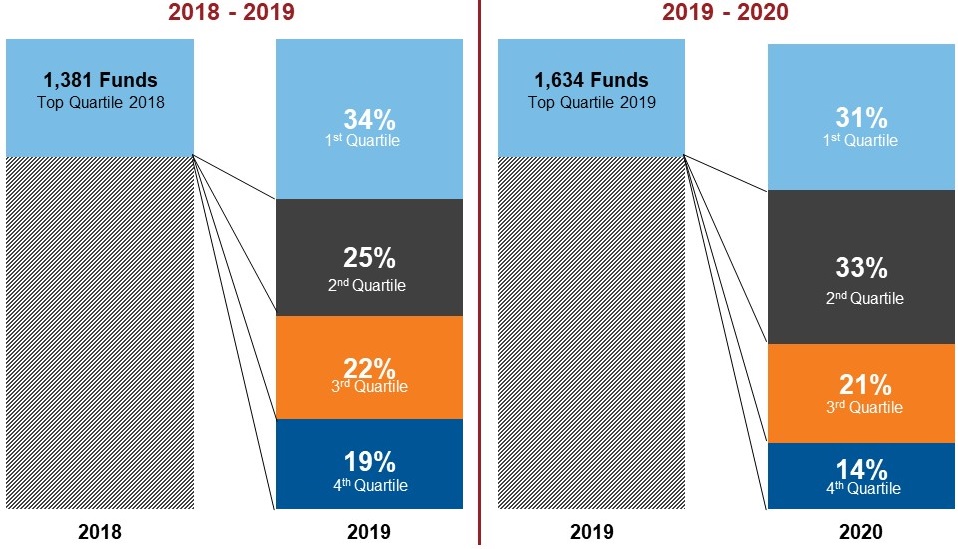

Styles go in and out of favor

While the stretch of leadership of large cap growth since 2017 has been compelling, it also has been unprecedented. Since the inception of the Russell style indexes in 1979, a single cap size and investment style combination has not led the market for four years in a row. Although many investors may feel this trend can continue, history has shown it may be the exception rather than the rule.

For example, from 2003-2016 no single size and style combination led the market in two consecutive years. The last example of a size and style combination to outperform for multiple years in a row was from 2000-2002 as small cap value outperformed for the three years following the bursting of the tech bubble, which was the last time the market was dominated by large cap growth.

As the chart below shows, it’s very hard to predict what style will be in favor and—more importantly—the cost of guessing incorrectly can be significant. Market leadership has varied across time, and no single size or style combination has been clearly dominant. Instead of trying to predict what might be in favor next, we believe advisors should consider representation of all styles in a client’s portfolio. We believe that when a portfolio has all styles represented, it is more likely to deliver positive results across a range of different markets, thereby letting you concentrate on long-term rather than short-term performance. This can help free more time to work with clients on their financial plan, and better understanding their goals. As we all know, the biggest detriment to a client’s return is often not what investment style is in their portfolio, but rather their own bad behavior, such as chasing returns or panic selling when the market falls.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Morningstar. Large Cap=Russell 1000® Index, Growth=Russell 1000® Growth Index, Value=Russell 1000® Value Index, Small Cap=Russell 2000® Index. The dark blue dots represent years not in the specific time periods noted.. Indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment.

How style can impact performance results

Many advisors start their fund selection process by looking at performance rankings within peer groups by style and cap size. For example, in evaluating a large cap growth manager against other large cap growth managers, you hope to get an more apples-to-apples comparison. However, while this may be a good starting point, careful examination often shows this may not tell the entire story.

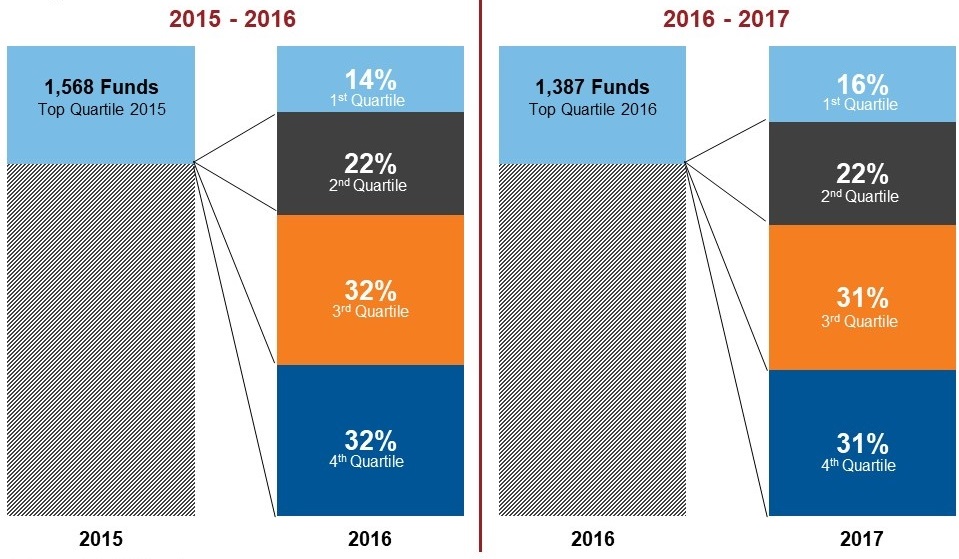

Over the last few years, picking U.S. equity funds based on recent peer-relative performance was not a bad approach to take. For example, in 2018 there were 1,381 U.S. equity funds with performance in the top quartile (top 25%) of their Morningstar category. A year later, at the end of 2019, 34% of those funds again finished in the top quartile of their peer groups while nearly 60% of funds finished in the top half of their peer group (1st or 2nd quartile). Perhaps more importantly, fewer than 20% of funds that finished with top quartile results in 2018 fell to the bottom quartile in 2019.

The following year, from 2019 to 2020, the outcomes were very similar. Of the 1,634 funds that finished 2019 in the top quartile of their peer group, 31% of funds also finished in the top quartile in 2020, while nearly 65% of funds finished in the top half of their peer group. Again, a very small amount—less than 15%—of funds that finished with top quartile results in 2019 fell to the bottom quartile the following year.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Morningstar

Numbers may not equal 100% due to rounding

Morningstar categories include U.S. Large Blend, U.S. Large Growth, U.S. Large Value, U.S. Mid Blend, U.S. Mid Growth, U.S. Mid Value, U.S. Small Blend, U.S. Small Growth, U.S. Small Value

This seems to suggest that in selecting funds that have had good performance in the last three years, you are likely to continue to experience above-average results. However, keep in mind that large cap growth has outperformed in the that time period. This means the strategy of choosing a manager that was in favor in 2018 would have likely continued to work into 2019 and 2020.

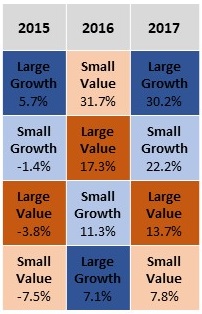

To see why this isn’t always the case, consider years like 2015-2017 which saw complete reversals in leadership from year to year.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Morningstar. Large Growth=Russell 1000® Growth Index, Large Value=Russell 1000® Value Index, Small Growth=Russell 2000® Growth Index, Small Value=Russell 2000® Value Index. Indices are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment.

Looking at the same type of fund rankings, results in 2018-2020 were essentially a mirror image from 2015-2017 results.

In 2016, as leadership flipped from large cap growth to small cap value, just 14% of funds that were in the top quartile of their peer group in 2015 remained there the following year. It was much more likely for a fund to underperform, as 64% of funds fell from top quartile to the bottom half of their peer group (3rd or 4th quartile) with 32% of funds in the last quartile—more than double the amount from 2019-2020.

When markets reversed again in 2017 and leadership flipped back to large cap growth, the results were nearly identical. Just 16% of funds that were top quartile in 2016 remained top quartile in 2017. Again, it was more likely for a fund to lag, as 62% of funds finished in the bottom half of their peer group with 31% in the 4th quartile.

Click image to enlarge

Numbers may not equal 100% due to rounding

Morningstar categories include U.S. Large Blend, U.S. Large Growth, U.S. Large Value, U.S. Mid Blend, U.S. Mid Growth, U.S. Mid Value, U.S. Small Blend, U.S. Small Growth, U.S. Small Value

The significantly different outcomes from 2015-2017 compared to 2018-2020 help illustrate the challenges of judging on past performance—even when comparing within the same peer groups. Although grouping managers based on similar strategies may be an attractive starting point for evaluation, there are still likely to be differences or bias within their portfolios that can affect results. Think of the following simple examples:

- A large blend manager with a portfolio tilted toward growth stocks may perform better than benchmark and peers when growth outperforms, but underperform when value is in favor.

- A deep value manager may be categorized with other value peers, but likely will have a significantly different portfolio and return pattern than a value manager who simply avoids owning companies with valuations that appear expensive.

- A small cap manager that has attracted a significant amount of new assets may be forced to look beyond small cap stocks to effectively allocate some of their capital, resulting in allocations to mid or possibly large cap stocks. Alternatively, a large cap manager trying to boost returns may invest a portion of their portfolio in mid or small cap stocks.

All of these biases embedded in a portfolio can have a significant effect on returns and help explain just why so few funds continue to remain at the top when market leadership changes. A manager that is currently showing strong results compared to peers could be simply benefiting from an investment strategy that places a larger weight to areas of the market that are currently in favor. However, as this trend reverses, this unfortunately could also result in unexpected stretches of underperformance once different areas of the market begin to outperform. The same factors that result in current top-performing managers all being successful at the same time ultimately could result in all of them being unsuccessful at the same time as well. This is why when it comes to evaluating and picking managers, it is important to look beyond performance and instead try to gain a deeper understanding of what is driving that performance and what types of markets could result in success in the future.

The bottom line

Market leadership has rotated over time and having exposure to managers representing multiple styles is critical to successful investing. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to always select the top managers and it is even more difficult to determine when to terminate a manager. Successful investing is challenging enough without trying to chase only those managers or funds that are leading. As we all are constantly reminded, past performance does not guarantee future results. However, researching money managers to get a deep understanding of how they invest can be extremely valuable. Partnering with a firm that not only understands managers, but knows how to pair managers with different styles can help deliver a portfolio that has the potential to be successful no matter the market environment.

1All returns in USD.