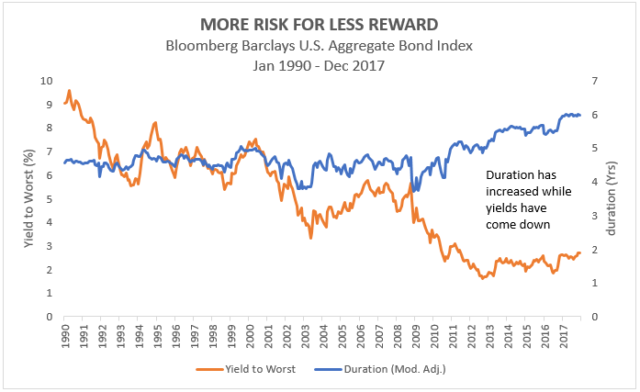

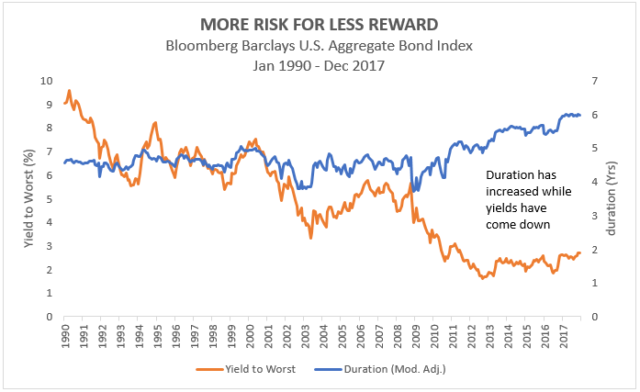

With the Federal Reserve poised to continue raising interest rates incrementally in 2018, many investors are eyeing their bond portfolios with trepidation. It’s true: Bond investing today isn’t what it once used to be, especially when you consider the changes to the duration and yield of the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, the common reference benchmark for core bonds. In our opinion, that’s not an excuse to bail on bonds though.

The current state of today’s bond market

On December 31, 2017, the duration of the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index stood at 6.0 years, eclipsing its 15-year average, which is in the 4-year range. During that time, the index’s yield has also compressed, as coupons on new bonds have declined, reducing the benchmark’s expected income.

Why is this relevant beyond the fixed income geekosphere? Because duration, which is the weighted average of cashflow from both coupon and principal repayment, is a measure of the sensitivity of a bond’s price to a change in interest rates. The longer the duration, the more sensitive the bond is to a change in interest rates. With interest rates expected to rise from their low levels, the index’s longer duration gives the returns from the bellweather benchmark less margin for error. Taking on interest rate risk (duration) when bond yields have decreased means the risk/reward tradeoff for bond investors has been reduced relative to history. Meaning the index could potentially experience low—if not outright negative—absolute returns from bonds with small increases in interest rates.

Source: Bloomberg Live as of 12/31/17

Source: Bloomberg Live as of 12/31/17

Before we address what investors may consider doing in response to adapt their fixed income exposure, it can help to understand how we wound up in this situation in the first place. Let me take you on a little trip down memory lane.

Why has duration of the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index extended?

The composition of the overall U.S. bond market was transformed in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Extended duration of the investment grade corporate and mortgage sectors

Lower interest rates and changes to the shape of the yield curve following the GFC allowed many bond market participants to refinance the terms of their debt. For corporations that meant issuing their debt at a lower coupon rate and extending the time period in which the debt comes due. Issuing longer dated debt at lower coupon rates has the effect of extending the duration of the sector.

Similarly, in the Mortgage sector duration has extended and turnover has decreased since the GFC. Many homeowners with existing mortgages have already used the low rate environment to refinance. Decreased refinancing activity slows down the pre-payments of mortgages. This is because a vast majority of mortgage pre-payment events result from either a refinance of the loan or the sale of the property. For those getting new mortgages, in addition to tighter lending standards, interest rates on new mortgages are low, and thus less likely to be refinanced in the future, further slowing mortgage pre-payment expectations. If interest rates rise, the incentive to refinance will continue to go down - which means more homeowners are likely to repay over the full term of their loan, thus extending the duration of the mortgage sector as a whole.

Increased issuance of U.S. Treasuries

The federal government significantly increased the issuance of U.S. Treasuries and purchases of agency mortgage-backed securities in their effort to stimulate the economy. While at this point this policy has arguably had its desired effect, it also created a situation where the Federal Reserve became the price-setter in the two largest sectors of the bond market, distorting the true equilibrium market value for Treasury and agency mortgage bonds.

How may investors consider adapting their portfolio?

When viewed in isolation, this information could lead investors to conclude that they should either meaningfully

reduce their overall exposure to core bonds or

modify the duration of their core bond exposure. I would argue there’s a third option, particularly when viewed within the context of an overall portfolio and today’s stretched equity market valuations:

complement and

broaden.

Appreciating the complementary role of bonds

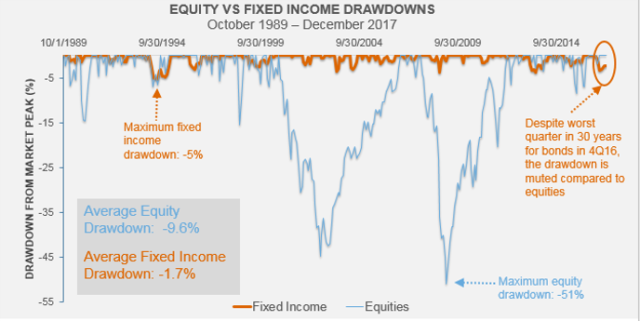

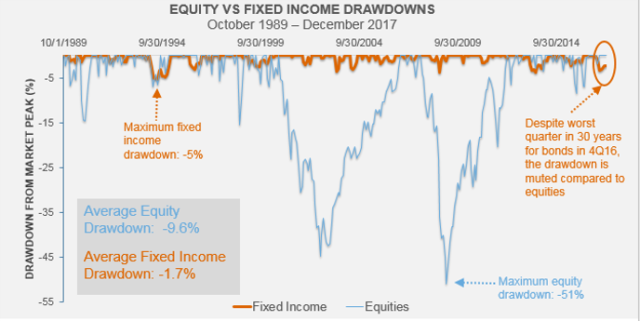

Core bonds in particular provide a complementary ballast to the overall equity exposure in the total portfolio. In other words, if a portfolio owns equities, it should also own core bonds with very few exceptions. Although bonds may generate a negative return, that dip historically has been much more muted than it is in equities, as the chart below illustrates. The largest fixed income drawdown since 1989 was -5%. There’s no doubt that was a painful period for bond investors. However, that drawdown is dwarfed by the -51% maximum equity drawdown over that same time period. At Russell Investments, we do not currently expect an equity drawdown of that magnitude to occur in the near future, however, given today’s lofty U.S. equity market valuations, we caution against abandoning the bond ballast in a portfolio in favor of more equity exposure.

Drawdown: The peak-to-trough decline during a specific period. Quoted as the percentage between the peak to the trough.

Source: Morningstar monthly max drawdown % for the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (“Fixed Income”) & the S&P 500 Index (“equities”) from 10/1/1989 to 9/30/2017. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment.

Broadening bond exposure

Drawdown: The peak-to-trough decline during a specific period. Quoted as the percentage between the peak to the trough.

Source: Morningstar monthly max drawdown % for the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (“Fixed Income”) & the S&P 500 Index (“equities”) from 10/1/1989 to 9/30/2017. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment.

Broadening bond exposure

Instead investors may consider diversifying their overall bond exposure beyond the typical Treasury, government-related, investment-grade corporate, and securitized bonds included in the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index. The additional diversification can help guard against potential interest rate increases without necessarily eliminating the portfolio’s duration completely. After all, removing duration from a bond portfolio reduces the diversification benefit of bonds relative to equities. Unconstrainted bond solutions—which typically invest in a wider range of fixed income sectors, such as high yield, mortgages, asset-backed securities, emerging market debt, in addition to investment-grade corporate bonds—may serve as “shock absorbers” against rising rates without adding equity risk to the overall portfolio.

The bottom line

Changes in the bond market since the Global Financial Crisis make core bond allocations more vulnerable to interest rate rises than was historically the case. We believe that should not deter investors from continuing to include a dedicated fixed income allocation in their overall portfolio. Rather, they may consider broadening the diversity of their fixed income investments to help prepare their portfolio for an environment of potentially rising interest rates.

Source: Bloomberg Live as of 12/31/17

Before we address what investors may consider doing in response to adapt their fixed income exposure, it can help to understand how we wound up in this situation in the first place. Let me take you on a little trip down memory lane.

Source: Bloomberg Live as of 12/31/17

Before we address what investors may consider doing in response to adapt their fixed income exposure, it can help to understand how we wound up in this situation in the first place. Let me take you on a little trip down memory lane.

Drawdown: The peak-to-trough decline during a specific period. Quoted as the percentage between the peak to the trough.

Source: Morningstar monthly max drawdown % for the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (“Fixed Income”) & the S&P 500 Index (“equities”) from 10/1/1989 to 9/30/2017. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment.

Broadening bond exposure

Instead investors may consider diversifying their overall bond exposure beyond the typical Treasury, government-related, investment-grade corporate, and securitized bonds included in the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index. The additional diversification can help guard against potential interest rate increases without necessarily eliminating the portfolio’s duration completely. After all, removing duration from a bond portfolio reduces the diversification benefit of bonds relative to equities. Unconstrainted bond solutions—which typically invest in a wider range of fixed income sectors, such as high yield, mortgages, asset-backed securities, emerging market debt, in addition to investment-grade corporate bonds—may serve as “shock absorbers” against rising rates without adding equity risk to the overall portfolio.

Drawdown: The peak-to-trough decline during a specific period. Quoted as the percentage between the peak to the trough.

Source: Morningstar monthly max drawdown % for the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (“Fixed Income”) & the S&P 500 Index (“equities”) from 10/1/1989 to 9/30/2017. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment.

Broadening bond exposure

Instead investors may consider diversifying their overall bond exposure beyond the typical Treasury, government-related, investment-grade corporate, and securitized bonds included in the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index. The additional diversification can help guard against potential interest rate increases without necessarily eliminating the portfolio’s duration completely. After all, removing duration from a bond portfolio reduces the diversification benefit of bonds relative to equities. Unconstrainted bond solutions—which typically invest in a wider range of fixed income sectors, such as high yield, mortgages, asset-backed securities, emerging market debt, in addition to investment-grade corporate bonds—may serve as “shock absorbers” against rising rates without adding equity risk to the overall portfolio.