Capital gains distributions: The trend is not your friend

Some trends are better than others. Big screen movies going direct to streaming services to watch at home? Count me in. Staring at your phone to watch a seemingly endless stream of TikTok videos? While my kids are in, count me out. Who has the time? Another trend not as obvious as TikTok, but no doubt as painful, is the annual repeat of material capital gains distributions coming from mutual funds. For taxable investors, these distributions reduce both after-tax returns and after-tax wealth. Tax-smart advisors can help manage this wealth erosion.

Every year, mutual funds (both active and passive) add up their realized gains and losses for the fund’s fiscal year (typically Nov. 1-Oct. 31). If the realized gains are greater than the losses, the fund is required to distribute each investor’s pro-rata share of those gains. Most funds start publishing their capital gains estimates in October and November, with the actual amounts posted and paid in December. For taxable investors, they will feel the sting of these amounts in 2022 with the receipt of Form 1099s in January and related taxes due on April 15.

How has this experience been for taxable investors in recent years?

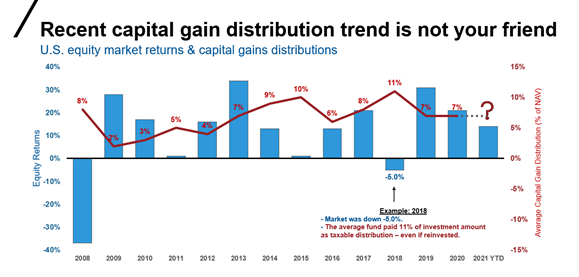

Let’s just say it’s not like one of those sometimes-funny TikTok videos. Exhibit 1 shows the trend since 2008. The red line represents U.S. equity funds’ average distribution as a percent of net asset value (NAV). For example, in 2018, the average U.S. equity fund distributed 11% of its NAV as a taxable distribution. For a taxable investor with a $100 investment in one of those funds, they would have owed, on average, tax on $11 of that investment—even if they chose to automatically reinvest the distribution. Note that 2018 wasn’t an exception: That red distribution line is never below zero, meaning there have been distributions—on average—every year, regardless of how the market has performed. There is often little correlation between how the market performs and the size of the average distribution.

What does the situation look like for taxable investors this year?

Note the question mark -? - over 2021 year-to-date (YTD) for the capital gains distribution percentage of NAV. We don’t know precisely yet what the percentage will be. But the trend doesn’t appear promising, given the attractive stock market returns since 2009, with only one negative year over the last 12 years.

Exhibit 1:

Click image to enlarge

2021 YTD: As of September 30, 2021. Source: Morningstar. U.S. Stocks: Russell 3000® Index. U.S. equity funds: Morningstar broad category ‘US Equity’ which includes mutual funds and ETFs (and multiple share classes) .% = Calendar Year Capital Gains Distributions / Year-End NAV. For years 2001 through 2013, used oldest share class. 2014 forward includes all share classes. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment.

So, what can a tax-smart advisor do to prepare clients for those likely Form 1099s?

We wrote previously about the four A's of preparing for capital gains season – Awareness (financial professional login required), Assessment, Action and Advocacy.

Fund companies are starting the process of posting their estimates for capital gains. Now is the time to be aware of the size of these estimates and potential impact across your practice. Being in front of these distributions is key to all of the four A’s.

Be aware that some fund companies pay capital gains distributions twice a year—not just at year-end. This may smooth out the payment amount (two smaller bites versus one big bite) but does not reduce the total distribution and total tax bill. From the Internal Revenue Service's (IRS) perspective, $1 + $1 = $2. Reporting only $1 in December may keep a fund off a list of high distribution funds—but it does not reduce the investor’s total tax bill.

At Russell Investments, we post our capital gains estimates every month—all year long. This transparency could help you in planning and give you insight into your clients’ tax situation.

And while talking about the timing of these estimates, ensure you and your clients make informed decisions about any material investment in a fund that is anticipating a capital gain between now and year-end. Buying now will saddle you with a taxable distribution as if you had been invested all year—regardless of the fund’s return. It’s referred to as buying the distribution—and can make for uncomfortable client conversations about their taxable accounts.

You didn’t sell any shares during the year. So why do you owe a tax?

Investors may be confused about why they owe taxes on their investments when they didn’t sell anything during the year. And if they reinvested the distribution, they may wonder why they owe tax on a gain they never benefited from.

Both are great questions, but the rules are the rules. Even if dividends and capital gains are reinvested, generally, the IRS considers the distribution as constructive receipt and a taxable event.

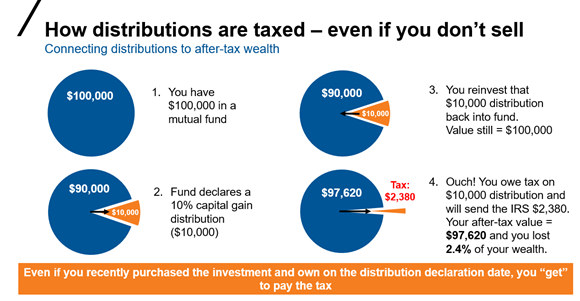

Exhibit 2 takes us step-by-step through the process.

1. Assume you have a $100,000 invested in a mutual fund.

2. The fund declares a 10% distribution based on gains recognized during the year within the fund. 10% of $100,000 = $10,000 distribution.

3. You reinvest the $10,000 back into the fund. $90,000 + $10,000 = $100,000. You feel no worse off: Money out = Money in. Wrong! The following January, you will receive the IRS FORM 1099-DIV, informing you of $10,000 of capital gain income.

4. After you pay the tax on the $10,000, you are $2,380 lighter in the pocketbook, and you have a 2.4% loss in after-tax wealth. Your after-tax wealth: $90,000 +$10,000 - $2,380 = $97,620. Ouch!

The headwinds of these taxes are often missed by investors when they pay their taxes from a different account than their investment account and don’t properly connect the dots. The example above illustrates a 2.4% fee paid to the government.

Note the above math assumes the distribution was long-term in nature. If any of the distributions were short-term, the tax rate would likely be higher for that portion and result in a higher tax bill. And none of this takes into account any state taxes—if applicable.

Exhibit 2: Pac-Man effect of taxes

Click image to enlarge

For illustrative purposes only. Assumes long term capital gains tax rate of 23.8%.

The capital gains distribution trend is not your friend

As you head into the fall and winter, be on the look-out for capital gains distributions. You can easily track capital gains estimates for Russell Investments funds throughout the year. We’re proud of our record of dialing down tax drag and striving to maximize after-tax return for investors. We would very much like to partner with you and your tax-sensitive clients.