Direct indexing: An efficient way to turn tax losses into tax assets

You’ve probably heard the phrase every cloud has a silver lining. It’s generally used when something bad happens that has a positive side effect. For example, let’s say your reservation at a restaurant was overlooked and you had to go somewhere else for dinner. And at the new restaurant, you ran into a friend you hadn’t seen in years.

Let’s consider the current volatility in financial markets as the cloud looming over the return potential of your clients’ portfolios this year. With the U.S. Federal Reserve rapidly hiking rates to rein in raging inflation, the ongoing war in the Ukraine and supply chain issues cutting into corporate profits, the outlook appears grim. But it does have a silver lining: the market’s ups and downs provide an ideal opportunity to tax-loss harvest. And an ideal opportunity to showcase how direct indexing is—by far—the most efficient way to reap the benefits of tax-loss harvesting.

The central goal of direct indexing is to build a portfolio that imitates an index mutual fund or exchange-traded fund (ETF) while maintaining all the flexibility of holding each security separately. The advantage that direct indexing holds in volatile markets is that since the investor owns the individual securities instead of a comingled fund, the losses that are taken on declining stocks belong to them. The investor can use those losses later to offset gains. That can be extremely helpful in reducing the investor’s tax bill.

Tax losses are tax benefits

As we’ve discussed previously, tax-loss harvesting by another name is tax-asset creation. While this may sound like Orwellian doublespeak, strategically selling some securities at a loss can be quite useful.

The thing is: capital gains are inevitable. No matter what the broader market does, there will always be some stocks that go up and some that go down.

Most mutual fund managers are solely focused on generating high returns without a consideration of realized taxes. That means they will sell their winners when they believe those stocks are no longer attractive and by doing so they realize a capital gain. During periods such as the past decade when most stocks rose substantially, even stocks that are down so far in 2022 could still be well above the price the manager paid for the initial purchase. So while the investor’s portfolio may have experienced a loss, the manager realized a gain in the fund and is required by law to distribute those gains (netted with any losses) at the end of the year. In fact, no matter what the equity market has done over the past 20 years, capital gains distributions have averaged 7% of net asset value (NAV) annually. Even in 2018, when the market (represented by the Russell 3000 Index) fell 5%, capital gains distributions averaged 11% of NAV. And since last year was a banner year—the market went up 26% and capital gains distributions averaged 12% of NAV—many of your clients may have received a substantial tax bill on those distributions in April.

Now imagine being able to give your clients the ability to offset those distributed gains with losses generated in a different part of their portfolio that tracks the index. This is where we believe direct indexing offers the best of two worlds: it provides the investor with index-like returns but with net tax losses. What’s not to love?

Something else to ponder about the current volatility and the current macroeconomic environment: Lower expected returns and potentially higher tax rates in the future make direct indexing look even more attractive.

Let me explain.

The hierarchy of tax efficiency

Most mutual funds are inherently not tax-efficient. They are required to distribute their capital gains to shareholders annually and don’t engage in tax-loss harvesting. Investors will probably receive a tax bill on those distributions and don’t have any choice in the securities held in the fund: they must buy or sell shares of the fund itself, which includes all the underlying constituents.

Tax-managed mutual funds are far more tax efficient because they will often tax-loss harvest to offset capital gains and thus reduce or even eliminate taxable distributions. But the investor still must buy or sell shares of the comingled fund. And the tax losses can only be used to offset the realized gains in that specific fund. Net gains are required to be distributed, while net losses cannot be distributed and are carried in the fund.

ETFs are also relatively tax efficient, mainly because their mandate to track an index means there is less turnover, which is often what generates capital gains and losses. They also can work within the tax code to clean out appreciated securities through tax-advantaged accounts.

With direct indexing, the investor owns the actual basket of stocks that are representative of the chosen index. For example, the Russell Investments Personalized DI Large Cap Separately Managed Account (SMA) could hold between 200-300 names in the S&P 500® Index.

Any losses harvested belong to the investor and can be applied indefinitely against any future gains on federal tax returns. Or they may be used to offset up to $3,000 of ordinary income annually. In fact, these losses can be used to offset gains not only in an investment portfolio but also those resulting from the sale of a home or business. See what I mean by useful?

Additionally, when an investor in a comingled fund sells the fund, they are effectively selling shares that contain all the securities in the fund. But with Direct Indexing, the manager can selectively avoid selling the top gainers.

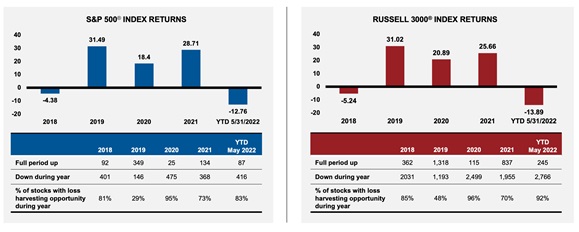

We suggest you show your clients the chart below so they can see how many of the individual names within the S&P 500® Index were losers in the past four years, even though the index itself rose significantly in three of those years. This may get them thinking about the losses they may have been able to take—and bank against their gains—while still receiving index-like performance.

Even in up years, there are opportunities for loss generation

Click image to enlarge

Analysis is based on S&P 500® Index and Russell 3000® Index constituents as of 5/31/2022. Full period up indicates stocks that were never down YTD at the end of any month during the year. Down during year means stock was down YTD at the end of at least one month during the year. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Personalized Managed Accounts – may be the best vehicle for direct indexing

Direct Indexing within the Personalized Managed Accounts (PMA) program may be an even better choice. The personalized SMAs can be managed for tax efficiency, and tax-loss harvesting would be an essential part of their broad tax-management toolkit. With PMA the investor can use losses in one SMA to offset gains in other holdings in their overall household level account.

In addition to Russell Investments' offering of three active SMAs and three direct indexing SMAs within its PMA structure, we also offer two core equity solutions. One is a combination of active and direct indexing strategies. Another combines two direct indexed strategies into a single SMA. The benefit of these single-sleeve portfolios is a single strategy can be purchased and paired with other diversifying asset classes such as fixed income to round out the risk profile of an individual.

The bottom line

While a direct indexing strategy is a great addition to an investor’s portfolio, you’ll want to ensure your clients are properly diversified and also poised to reap the benefits of active management, while recognizing that active management doesn’t generate as many tax losses as tracking the index does.