Another way to think about tax-loss harvesting: Tax asset creation

Tax-loss harvesting—also called tax harvesting or loss harvesting—is a strategy in which an investor intentionally sells an investment at a loss in order to offset capital gains taxes on other investments that have been sold at a profit.

Here is the thing: this phrase confuses many individual investors. It's just semantics. Another way to think about tax-loss harvesting is to call it tax asset creation. Too many people focus on just the L word in tax-loss harvesting instead of thinking about how the total picture comes together. By having this strategy—tax asset creation—embedded in the investor's total solution, the focus becomes on improving and maximizing after-tax wealth.

The result of tax-loss harvesting is that taxes are only paid on the net profit—the difference between the gains and the losses. This can significantly reduce an investor's tax bill. Fewer taxes going to the taxman could mean more money left in your client's account to invest and grow. That sounds pretty good to me. Does it sound pretty good to you?

Who might benefit from loss harvesting?

Any investor with taxable assets and seeking to maximize after-tax returns could very well gain from successful tax-loss harvesting. For taxable investors, the pre-tax return shown in quarterly performance statements can have little bearing on their ability to achieve their financial goals. It's the difference between gross and net. The amount that's after-tax will ultimately help these investors get to where they are going. Productive tax-loss harvesting could make a big difference in maximizing after-tax returns for taxable investors.

What may prevent investors from harvesting losses?

One of the biggest obstacles to this strategy being used effectively is often the investors themselves. Most people don't like hearing they've lost money. They find it difficult to sell an investment at a lower price than they bought it at. The term loss-harvesting requires them to acknowledge an investment loss. In other words, they feel they are admitting they were wrong. So, psychologically, it can be difficult to tax-loss harvest.

- We don't like to admit that we're wrong. So instead of selling, we hold onto our losing positions. We do this in the hope they'll eventually recover. Hope is not an investment strategy!

- There is an established psychological theory known as the disposition effect. It basically says investors tend to sell assets that have increased in value, while keeping assets that have dropped in value. In essence, sell winners and keep losers … what might that do to a portfolio over the years?

When should investors be doing tax-loss harvesting?

Most investors don't think about tax-loss harvesting their portfolio until near the end of the year. Many wait because they are busy and tend to procrastinate. But it also could be that as the year comes to an end, some investors realize they may be facing large capital gains taxes. In order to enjoy the tax benefits of harvesting losses, sales transactions need to be finalized before the year ends. So that often sparks a flurry of selling in the last two months.

From a calendar planning perspective, it does make it easier for many investors to schedule tax-loss harvesting for the end of the year. But investors also are likely to be missing more attractive opportunities throughout the year to harvest losses.

Since 1926, the U.S. stock market, based on the S&P 500 Index, has ended the year positive more than 70% of the time. Over the past 70 years, based on FactSet data, in terms of monthly returns:

- November has been the single-best stock market month.

- December has been the third-best stock market month.

In other words—on average—waiting until November and December to perform tax-loss harvesting may be limiting investors to two of the worst months to harvest losses.

As the chart above shows, it's important to actively manage for taxes throughout the year. Having this be just an end-of-year exercise may limit the benefits your clients can get from it. Moreover, in addition to loss harvesting, there are more active tax-managed strategies available to mitigate the tax drag in investment portfolios. These also can be implemented through the entire year.

When it comes to harvesting tax losses throughout the year, does timing matter?

Absolutely. Done correctly, tax-loss harvesting takes advantage of market corrections and volatility—in a sense turning lemons into lemonade. The volatility seen in the first few months of 2022 is a good example. This is now three years in a row we have seen such volatility in the first few months of the year. The January dip and February swoon could have been an ideal time to tax-loss harvest. Advisors need to be ready to act—and to act quickly. As an advisor, you also need a systematic process to understand which clients may benefit.

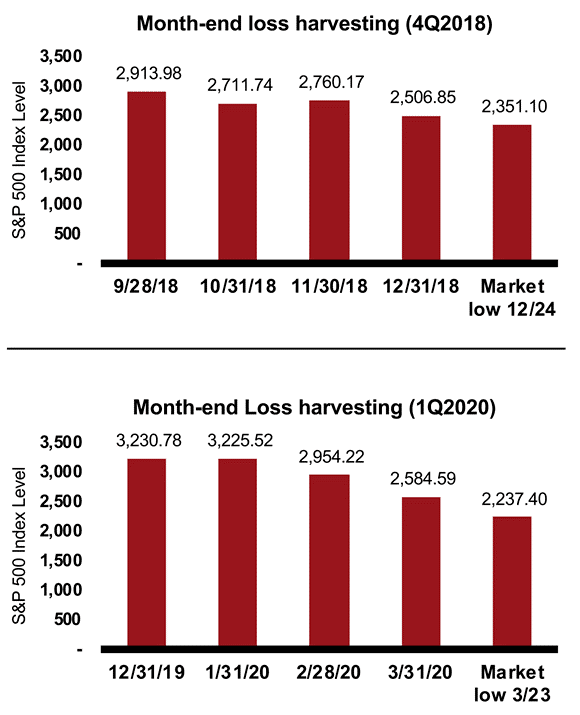

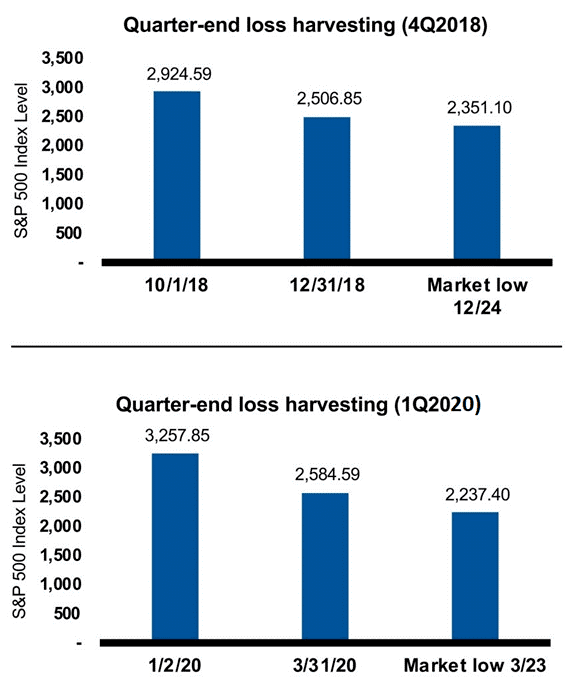

Let's look at the last two 15%+ market corrections: in the fourth quarter of 2018 and the first quarter of 2020.

Did the timing of tax-loss harvesting matter? What if tax-loss harvesting was systematic through a partnership with an overlay manager? And what if the overlay manager's process only looked at valuations on month- or quarter-end? Let's look at two different scenarios:

1. Loss harvesting at quarter-end

2. Loss harvesting at month-end

1. Quarter-end loss harvesting:

Click image to enlarge

For illustrative purposes only.

2. Month-end loss harvesting:

For illustrative purposes only

Note that for month-end dates, again, the best time to harvest losses (market low) was not at the month-end.

It's easy to see the difference between the market low and the month-end or quarter-end. While no one can call the market bottom during the moment, having a process that looks beyond specific dates widens the opportunity set to achieve better results from loss-harvesting efforts. The illustrated differences show the importance of having a systematic tax-loss harvesting program that is monitored and run constantly, whenever markets are open. We believe the best tax-managed programs have robust, experienced, in-house trading capabilities that are laser-focused on seeking the optimal after-tax returns for investors and are prepared to harvest losses whenever they occur, even if the trading activity falls on Christmas Eve.

Do investors have to be in the top tax bracket for loss harvesting to work?

No. It is obvious that if an investor is in a higher tax bracket, tax-loss harvesting will have a more meaningful benefit. But there is value in the exercise for those in lower tax brackets. Consider an investor with a marginal tax rate of 24.0% (plus the 3.8% net investment income tax), for a top federal rate of 27.8%.

If you are able to harvest short-term losses equal to $30,000, this harvested loss could be used to offset against short-term gains for tax bill savings of $8,340 ($30,000 x 27.8%). This could be a meaningful reduction in the investor's tax bill! For long-term gains, you would use the investor's long-term capital gains tax rates accordingly.

The higher the tax bracket, the bigger the bang for the buck. But as we demonstrated there may be lots of bang for those in lower tax brackets.

Sounds easy enough to do for one investor. What about for multiple investors? Is scale an issue when it comes to tax-loss harvesting?

It can be. Advisors don't only work with one investor or one taxable account. And, it's more than just the quantity of work we are referring to (which can be sizable). The multitude of accounts an advisor manages translates to every investor having a specific starting point. Each investor's cost basis is unique and the advisor needs to be sensitive to each situation. Add in the impact of reinvesting of distributions, client withdrawals, marginal tax rate changes—all for every client across your practice and it gets complicated very quickly. Scale can become an issue without a systematic and sophisticated way of doing tax loss harvesting.

What other mistakes are common when it comes to loss harvesting?

Other than waiting until year-end, quarter-end or month-end, there are three other typical mistakes advisors can make with do-it-yourself tax-loss harvesting:

1. Opportunity cost - After harvesting the loss, being in cash for 31 days or choosing the wrong replacement security

When you harvest a loss, you are selling a security. What should you do with the cash proceeds from the sale? Some investors choose to hold cash while waiting 31 days before repurchasing the original security to avoid the wash sale rule. In a downward trending market, this may be a fine strategy. But advisors often want to keep the cash proceeds invested in the market—typically in a security with very similar characteristics as the original security. If purchasing a replacement security, make sure it has similar characteristics (such as cap size, style, industry, etc.) as the original holding—but is still substantially different (see #2 below). Also, consider whether the client's asset allocation needs have changed. If not, avoid introducing any unintended risks or deviations from your policy portfolio via the new security. At 31 days or later, consider reverting back to the original security—if the investment rationale still holds.

2. Wash sale rule breach - Buying a similar security and having the loss disallowed

When making the sale and purchasing a replacement security, make sure the replacement security is substantially different in character. Some aspects to pay attention to include fund share class, benchmark, security type, etc. The IRS can be very particular about rules requiring the new security to be different in nature than the original purchase. If the securities are too similar, the loss may be disallowed, causing the entire effort to be of no avail.

3. Worth the effort - Making sure the juice is worth the squeeze (understand the materiality)

This isn't a process you want to do every time a security goes down in value. Consider the size of the portfolio, magnitude of the downturn and costs related to the trades. If your client is in the top tax bracket, take the amount of loss harvested and multiply by 40.4% for short term gains (37.0% + 3.8% for net investment income). That's how much you are creating in potential tax savings or a tax credit. Again, this only works if you have current gains in the portfolio or can carry forward into future periods.

If tax-loss harvesting requires so much focus, does it make sense for advisors to simply outsource the effort by using tax-managed funds or model portfolios?

It can, if the right provider and solution are selected. It is important to look at the after-tax return that a solution provides. We believe too many investors and advisors focus on pre-tax performance numbers.

For investors with taxable portfolios, what really matters is not what their investments make, but what the investor gets to keep, after taxes.