What is tax-loss harvesting? It’s a way to create a tax asset.

Executive summary:

- Investment gains in a portfolio create value. But you can also create value by creating tax assets that help minimize the amount of taxes paid

- Tax-loss harvesting is an essential tax-management strategy that can benefit a broad range of taxable investors – even those who many not think they have to worry about investment taxes

- Advisors conducting tax-loss harvesting on their own should be wary of potential pitfalls and may wish to seek expertise to ensure their clients are in the right solutions to maximize their after-tax wealth

There are a number of ways to create value when investing. The main way most investors think about creating value is through purchasing an asset like a stock whose price rises. That price increase equals a profit and therefore has created value.

But…. How does this work in a taxable portfolio? Profits are taxed. The profit that was created is therefore Pre-tax Value. After-tax, the profit is going to be lower; and in many cases it can be a lot lower. What can be done about that, if anything? There is another type of value than can be created within an investment portfolio: a Tax Asset. What is a Tax Asset, what is it good for, and how can you create it, you might wonder?

A Tax Asset is a type of credit that can be used to lower, and in some cases, eliminate, the tax liability associated with a profit. Now we are getting into creating After-Tax Value!

And how do you create this Tax Asset? You do it through tax-loss harvesting.

What is Tax Loss Harvesting?

Tax-loss harvesting—also called tax harvesting or loss harvesting—is a strategy in which an investor intentionally sells an investment at a loss in order to offset any

capital gains taxes on other investments that have been sold at a profit. The result is that taxes are only paid on the net profit – the difference between the gains and the losses. This can significantly reduce an investor’s tax bill.

Moreover, the difference can be harvested and used at a later time to offset future realized gains. These harvested losses can be considered a Tax Asset. Done correctly, deferring the recognition of gains and harvesting tax losses can both increase after-tax returns and help maximize after-tax wealth.

Who might benefit from loss harvesting?

Any investor seeking to maximize after-tax value may stand to gain from successful

tax-loss harvesting. For taxable investors, the pre-tax return they see in quarterly and annual performance statements can have little bearing on their ability to achieve their financial goals. It’s the amount after taxes are paid that will ultimately help these investors get to where they are going. Productive tax-loss harvesting could make a big difference in maximizing after-tax returns for taxable investors.

Moreover, it’s not just a single calendar year that matters. What matters is the growth of their assets over the full duration of their investment time horizon. And we’re not just talking about their working years, but also into and through their retirement years. Taxes don’t just go away -- they are here with us throughout our lives.

What may prevent investors from harvesting losses?

One of the biggest obstacles to this strategy is often the investors themselves. Most people don’t like hearing they’ve lost money and find it even more difficult to sell an investment at a lower price than they bought it at. The term loss-harvesting requires them to acknowledge that they’ve lost money on an investment; in other words, admit they were wrong. And it requires them to actually sell the investment at a loss.

So, psychologically, it can be difficult to tax-loss harvest.

We all have behavioral biases that may keep us from tax-loss harvesting:

- We don’t like to admit that we’re wrong. Instead of selling, we hold onto our losing positions in the hope they'll eventually recover.

- This is an established theory known as the disposition effect, which states investors tend to sell assets that have increased in value, while keeping assets that have dropped in value.

- Additionally, investors in many cases don’t understand the value that an activity such as tax-loss harvesting has. Taxes are paid on “net gains”. Investors often mentally place gains and losses in different buckets, and don’t always understand the math involved or the benefits of harvested losses.

Using a calculated and systematic approach to tax-loss harvesting is key. For many investors, that may mean that they need to let someone else take charge when it comes to thinking about tax management. It might be more palatable to embrace a process and a system for doing so that is unemotional and focuses on after-tax value.

When is the best time to do tax-loss harvesting?

Many advisors don’t discuss tax-loss harvesting with their clients until close to the end of the year. This isn’t just because they are busy. They do it because they start to realize their clients may be facing large capital gains taxes and if they hope to enjoy the benefits of harvesting losses, the sales transactions need to be finalized before the end of the year. However, while this might be easier from a calendar-planning perspective, investors may be missing more attractive opportunities throughout the year to harvest losses.

When is the best time to tax-loss harvest? The answer is easy: all year long! Markets are volatile. They are also unpredictable. For an activity such as tax-loss harvesting, it’s best to be ready at all times to take advantage of when the market moves and create that valuable tax asset.

We believe the best tax-managed programs have robust, experienced, in-house trading capabilities that are laser-focused on seeking the optimal after-tax returns for investors and are prepared to harvest losses whenever they occur, no matter whether the trading activity falls on New Year’s Eve, right before Labor Day, Christmas Eve or any day in between.

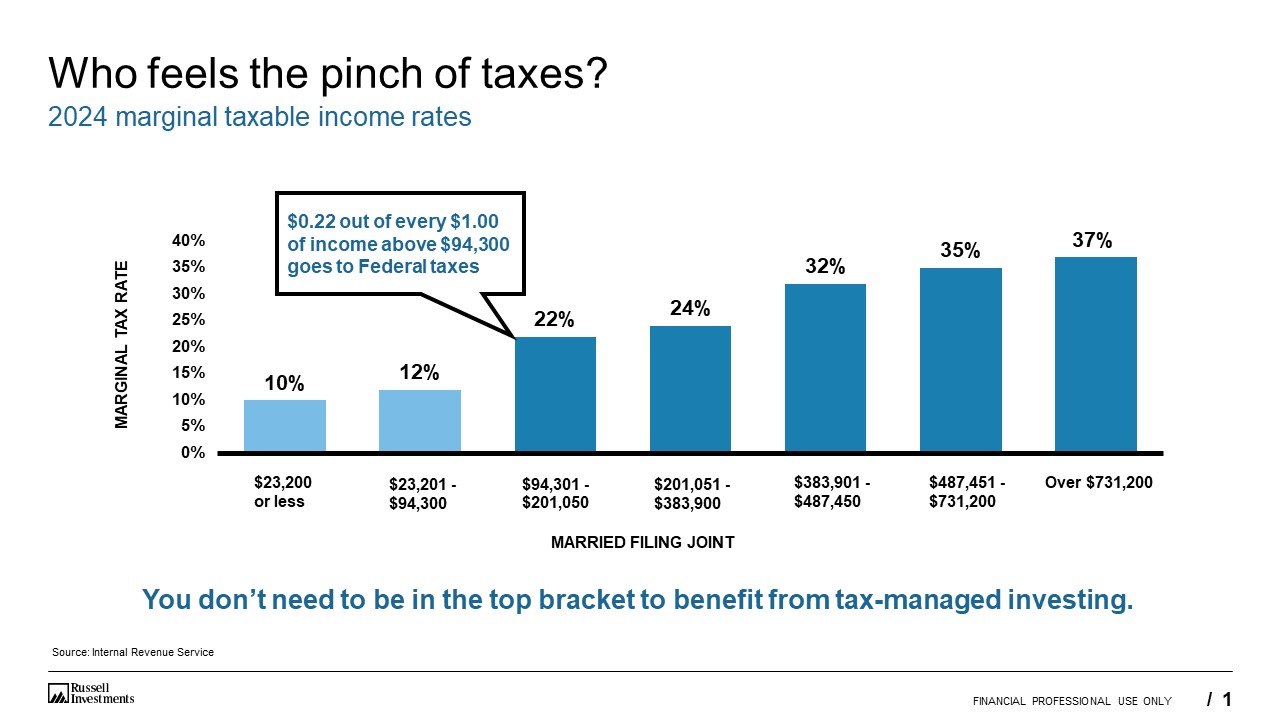

Do investors have to be in the top tax bracket for loss harvesting to work?

No. The higher an investor’s tax bracket, the more impactful tax loss harvesting is, but there may still be value in the exercise for those in lower tax brackets. Consider an investor with a marginal tax rate of 24.0% + 3.8% (Net Investment Income Tax) for a top federal rate of 27.8%. If you are able to harvest short-term losses equal to $3,000, this harvested loss could be used to offset against short-term gains for tax bill savings of $834 ($3,000 x 27.8). You would use the investor’s long-term capital gains tax rates accordingly. The higher the tax bracket, the bigger the bang for the buck. But there may be lots of “bang” for those in lower tax brackets.

Source: Internal Revenue Service

For a single tax filer, the tax brackets where tax management and tax loss harvesting make sense have an even lower income threshold. At just $41,776 of income, an individual slides into the 22% tax bracket. Many people making $42,000 to just under $90,000 of income might not think that taxes should be a major concern. But add in some compounding, and it’s easy to see how an investor with as low as $42,000 in income could be losing up to a quarter of their investment returns to taxes. That is a meaningful amount and highlights the value that tax-loss harvesting can bring to minimize the tax impact of realized capital gains.

Is scale an issue when it comes to tax-loss harvesting?

It can be. Advisors don’t only work with one taxable account. The multitude of accounts an advisor manages translates to every investor having a specific starting point. Each investor’s cost basis is unique, and the advisor needs to be sensitive to each situation. Add in the impact of reinvesting distributions, client withdrawals, marginal tax rate changes—all for every client across your practice. It gets complicated very quickly.

This makes scale difficult; and means that tax-loss harvesting and tax management are often an afterthought. With scale and an activity like tax-loss harvesting, advisors also need to consider equal-treatment rules. Being opportunistic when it comes to tax-loss harvesting becomes a luxury. Even thinking about performing tax-loss harvesting more than once a year is often a no-go. Better than the go-it-yourself route, this is where using tax-managed portfolios that allow for scale to occur naturally and more seamlessly is a better overall option. Scaling up with tax-loss harvesting and tax management allow for a more streamlined process for the advisor and a more than likely better after-tax outcome for the investors.

What mistakes are common when it comes to loss harvesting?

Other than waiting until year-end, quarter-end or month-end, there are three other typical mistakes advisors can make with “do-it-yourself" tax-loss harvesting:

- After harvesting the loss, being in cash for 31 days or choosing the wrong replacement security – When you harvest a loss, you are selling a security. What should you do with the cash proceeds from the sale? Some investors choose to hold cash while waiting 31 days before repurchasing the original security to avoid the wash sale rule. In a downward trending market, this may be a fine strategy. But advisors often want to keep the cash proceeds invested in the market—typically in a security with very similar characteristics as the original security. If purchasing a replacement security, make sure it has similar characteristics (such as cap size, style, industry, etc.) as the original holding—but is still substantially different (see #2 below). Also, consider whether the client’s asset allocation needs have changed. If not, avoid introducing any unintended risks or deviations from your policy portfolio via the new security. At 31 days or later, consider reverting back to the original security—if the investment rationale still holds.

- Buying a similar security and having the loss disallowed – When making the sale and purchasing a replacement security, make sure the replacement security is substantially different in character. Some aspects to pay attention to include fund share class, benchmark, security type, etc. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) can be very particular about rules requiring the new security to be different in nature than the original purchase. If the securities are too similar, the loss may be disallowed, causing the entire effort to be of no avail.

- Making sure the juice is worth the squeeze (understand the materiality) – This isn’t a process you want to do every time a security goes down in value. Consider the size of the portfolio, magnitude of the downturn and costs related to the trades. That’s how much you are creating in potential tax savings or a tax credit. Small, incremental tax losses may not be worth the time, effort, and trading costs. For an institutional-level portfolio, trading costs are often very low, allowing for smaller trades across a larger number of securities to generate good harvesting results. But for individual “retail” accounts, trading costs can add up fast and strip away a lot of the value created on small tax-loss harvesting activities. Make sure the value is there for the activity being performed, and as with scale, consider what after-tax value a professionally tax-managed portfolio can bring for the client.

Does it make sense for advisors to seek expertise for improved tax management and after-tax outcomes?

It can, if the right provider and investment solutions are selected. It is important to look at the after-tax return that an investment provides. We believe too many investors and advisors focus on pre-tax performance numbers. For tax-sensitive investors, what really matters is not what their investments earn, but what the investors get to keep, after taxes.