Exploring cash options? 5 questions advisors should ask

Executive summary:

- When markets are volatile, many investors move to the perceived safe haven of cash instruments

- Cash may currently appear attractive because high interest rates mean nominal returns are higher

- There are risks and tradeoffs to holding cash, such as the impact of inflation or the opportunity cost

Have you ever burned yourself while cooking? I know I have. Between scalding myself with pasta water and forgetting to wear an oven mitt to grab the frying pan, making dinner can be a risky proposition. Yet I continue to cook on a regular basis. After all, we need food to survive and achieve our most basic goal: staying alive!

You may also have been “burned” while investing. For example, 2022 was a tough year for many investors. Stock and bond markets both posted negative returns for the first time in more than 50 years. Since 1926, this has only happened twice: in 1931 and 1969.

But just like most people don’t abandon their dinner plans when they burn a finger, they shouldn’t abandon their investment plan when markets go against them.

This message may be of greater importance these days as higher interest rates mean that cash instruments such as Certificates of Deposits (CDs), money market funds and high-yield savings accounts are offering attractive nominal returns.

Some of your clients may be wondering if they should move out of the uncertain markets and into cash. Cash sounds like a safe option with all the bad news out there right now. Most Investors need cash for short term liquidity and emergency savings. However, above and beyond that, usually investors need long term real rates of return to fund their future goals like retirement, a home purchase, or a college education for their children.

If you know that some of your clients are considering an increase in their cash allocation here are five questions to ask to help them assess the risks and benefits:

1) What is the real return?

A real return is adjusted for inflation. Let’s use an example. Suppose a cash instrument is offering a 4% yield: If we take that 4% nominal return, subtract historical inflation (2%) that leaves us with a real return of 2%. For most investors, this level of real return doesn’t get them any closer to their long-term goals.

In this era of high inflation, this consideration takes on a different hue. With inflation around 6%, a cash instrument offering 4% provides a negative real rate of return. Investors would need a cash instrument offering more than 6% to grow their wealth in real terms, net of inflation.

2) What are the tax implications?

Cash instruments are typically taxed at ordinary income rates. If an investor is in the highest federal income tax bracket, investment income such as interest is taxed at 40.8%. The highest marginal tax rate is what the Securities Exchange Commission uses in its after-tax calculations; we’ll be conservative and use the same. Let’s do the math.

(Cash instrument interest rate) x (1- marginal ordinary income tax rate) = after-tax return

(4%) x (1-40.8% tax rate) = 2.37%

Now if we subtract historical inflation (2%) from the after-tax return we get an after-tax real rate of return of 0.37%.

This doesn’t assume any state income tax, which can make the outcome even more bleak. Let’s assume the exact same scenario as above, but for a California-based investor who pays the 9.3% state income tax.

(4%) x (1-40.8%+12.3% tax rate) = 1.876%

After taxes and inflation this is an after-tax real rate of return of –0.124%. Yes, that’s correct, a negative real rate of return.

How about using a lower tax rate? Let's assume a married couple filing jointly at the peak of their careers making a combined income of $400K. That’s a 35.8% investment income federal tax rate (32% + 3.8% for the ACA tax surcharge). And for our California investor, there is the state income tax again.

Here is the math:

(4%) x (1-35.8% tax rate) = 2.57%

After deducting the 2% historical inflation rate, that’s an after-tax real rate of return of 0.57%

And if you are in a state like California:

(4%) x (1-35.8%-9.3%) = 2.196%

After deducting the 2% historical inflation rate, that’s an after-tax real rate of return of 0.196%

Too many investors see “4%” and get excited... but they don’t do the math to understand what they actually end up getting out of that.

3) What are the re-investment risks?

Certain cash instruments are locked up for a period of time. Investors may view these instruments as short-term solutions and plan to redeploy those funds in 1, 2, or 3 years. But there are a few things that can change in the time between when an initial investment occurs and when that money is returned.

What if rates are significantly lower, so re-deploying into a cash instrument is not attractive anymore?

What if between the initial investment and when the capital is returned, alternative options such as equities have appreciated meaningfully?

Over the last few months I have heard multiple times that some investors plan to move to cash instruments temporarily, and then move back into equities after two or three years. When I ask the question of why this is the plan, I’m told that the investors fear a potential recession.

We looked at the data for the last seven recessions in the United States. After just one year from the start of the recession, an investor would have been positive a majority of the seven times had they invested the day the recession started. In six out of seven cases, if an investor had put money in the market the day the recession started, at the end of year three, their returns would have been positive. In most cases, the average annualized returns are meaningfully higher than what a short-term cash-like instrument has historically produced.

So think about the real investor example referenced above:

Step 1: Leave the market over recession fears and go into a cash instrument for three years

Step 2: At the end of year three, re-invest their capital. Not only may they miss a positive return period in the market, but they also now might be re-investing into a market with much higher valuations.

Click image to enlarge

Source: National Bureau of Economic Research (“NBER”) & Morningstar Direct. Recession start date and length as declared by NBER. Market Returns: S&P 500 TR USD Index. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly.

4) What is the opportunity cost?

When does cash have short-term periods of significant popularity? Usually during periods of economic uncertainty and equity market volatility. When have investors historically had some of the best opportunities to put money to work at lower valuations? During periods of economic uncertainty and equity market volatility.

Volatility leads to larger flows of money into the safe haven nature of money market funds. As the chart below shows, money market account balances have been increasing since 1993.

Click image to enlarge

Source: S&P 500 Index, Total Net Assets: U.S. Money Market Funds (including obsolete funds). As of 3/31/2023. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. **GFC refers to the Global Financial Crisis.

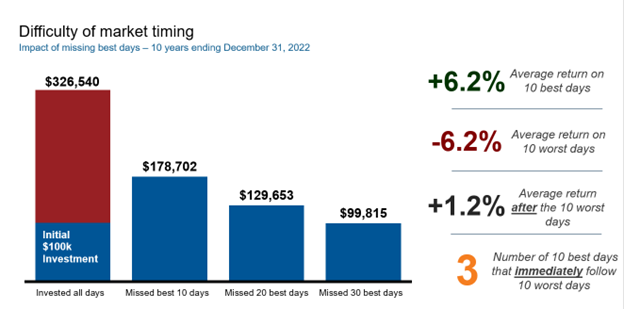

Now let’s look at a chart that highlights what happens if an investor misses the 10 best days in a decade of investing. A long-term investor must ask the question: how many of the potential 10 best days could I miss if I am out of the market for 12, 24 or 36 months? Furthermore, what is my opportunity cost?

Click image to enlarge

Source: Morningstar. Returns based on S&P 500 Index, for 10-year period ending December 31, 2022. For illustrative purposes only. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly.

Sometimes as investors, we have brief moments where we feel that “we must take action!”. Sometimes we feel that if we are not taking action, we aren’t being productive. It is important to remember that the decision to make no changes to a portfolio and remain invested is itself an action.

5) Are you selling long term investments to buy these cash instruments?

There’s a term for this – market timing. It sounds great on paper. Selling when the market peaks and moving to cash. Then buying back into the market when it bottoms. However, the trick is knowing when the market has peaked and when it has bottomed. That’s a guessing game that doesn’t always work so well, as the chart above shows.

When investors move to cash, it’s typically due to several behavioral biases driving their emotional response. Here are a few that may be the culprit.

- Herd behavior – which is because other people are moving to cash.Safety-in-numbers thinking.

- Myopic loss aversion – focusing on short-term losses and not the long-term potential for gains

- Anchoring Bias – cash rates have been low since the Global Financial Crisis, let’s take advantage of the higher rates now.

Ask your clients to think back to March 2020 before they sell their long-term diversified portfolio to buy cash. Were they invested in the stock market when it bottomed out three years ago? Did they remain invested or move to cash at that time?

How much could this have cost them in terms of lost return?

Click image to enlarge

Source: Morningstar Direct and BLS.gov. Balanced Portfolio: 60% S&P 500 Index & 40% Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index. As of Dec 31, 2022. Monthly change in CPI as of Dec 31, 2022. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly.

Investors may feel they have been “burned” multiple times over the past few years. It is understandable they may want to seek the perceived safety of cash instruments. Staying disciplined and diversified during periods of uncertainty is challenging. But that is where you, the advisor, comes in. As our annual Value of an Advisor study shows every year, your role as a behavior coach can help add substantial value to your clients’ portfolios. Helping investors understand the impact higher cash allocations may have on their long-term financial goals should be an important point for 2023 client review meetings.