The case for private markets, part 1: Plugging the gap

For a long time, public markets have been in what many have referred to as a Goldilocks period. Broadly speaking, growth has been occurring across most economies, market volatility has been low and inflation benign. On the surface, everything appears just right. But conditions are slowly shifting—and signs of change are afoot. For example:

- Global growth is still pretty solid, but slowing in some markets

- Inflation is low, but still present

- Market volatility has increased of late

Many market participants are expecting future returns in publicly listed markets to be lower than in the past. Though it’s impossible to predict when, the prolonged economic cycle will turn at some point, which is leading many institutional investors to consider allocating to private markets. Why? We see three main reasons:

- Diversifying risk;

- Seeking higher sources of returns from traditional investments, due to lower future return expectations, and;

- Preparing for rising interest rates.

Combined, we believe that these factors make private markets an attractive alternative to traditional asset classes.

A variety of plan types invest in private markets, which are particularly suited to investors with long-term time horizons and the liquidity budget to allocate to relatively illiquid assets. This includes endowments, hospital plans and other long-term pools. Pension funds have particular challenges that we believe could be offset by private-markets investing. Among them are that as return expectations for public investments decline, the net present value of a pension fund’s liabilities rise, leading to a potential funding gap. In addition, individuals are living longer today, which creates a longer tail to pension liabilities. Investing in private markets may help to mitigate these challenges.

Why else are institutions moving toward private markets? Because the investment opportunity set has changed.

In addition to the potential benefits of private markets and the signs of change in the current market backdrop, the investment opportunity set has changed over the last 20 years. Two significant differences from then and now are:

- 1.)The shrinking number of public companies—particularly in the U.S.; and

- 2.)The dramatic reduction in credit provided by banks.

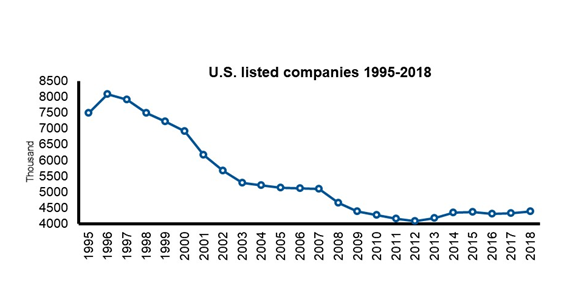

Source: The World Bank, “Listed domestic companies 1997-2017”. For illustrative purposes only.

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/CM.MKT.LDOM.NO?end=2018&locations=US&start=1985

The chart above shows the significant drop in the number of U.S. publicly listed companies over the last 20 years. In 1996, there were approximately 8,000, and today, there are about 4,300. The number of public companies today is roughly half of what it was a generation ago.

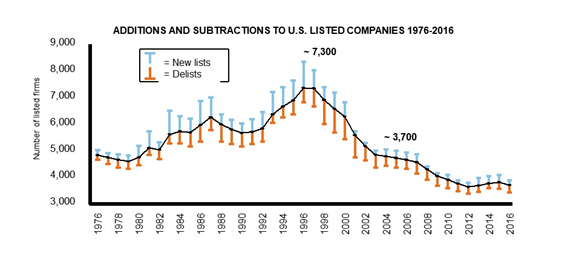

Remember that all businesses begin as private enterprises. While there are several reasons why a company may go public, de-list or remain private, there are a myriad of explanations as to why there are fewer public companies today. As noted in the Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 123, No. 3, companies have delisted for a range of reasons. Top among them are:

- Over a 20-year period, there’s naturally been some corporate consolidation as well as bankruptcies.

- Regulation has increased the cost of listing.

- Many private company founders believe that private markets are better at allowing them a long-term perspective in running their business.

- The U.S. economy has become more technology-intensive, meaning that many companies need to spend less on assets such as plants and equipment.

- Private markets, meanwhile, have become more sophisticated at supplying the capital they require.

Why does a lesser amount of public companies matter for investors? Simply put, because it changes their investment opportunity set. Historically, pension funds could get full exposure to the U.S. economy, for example, by owning a diversified group of equities, as well as a few venture capital funds to capture returns from start-ups. Now, institutional investors are forced to cast a wider net by making investments in a variety of private-market categories to gain exposure to the economy.

It’s worth clarifying that a lower absolute number of public companies does not necessarily correspond with a decline in the total value of market capitalization of public companies, which as a percentage of U.S. GDP was 105% in 1996 and 165% at the end of 2018.1 But most institutions require diversification, and would not have a concentrated exposure in large-cap equities.

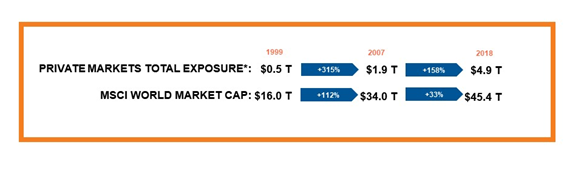

There is evidence of a growth in exposure to private markets over that same time period. The table below shows the growth of private markets over the last (roughly) 20 years—the same time frame during which the number of public companies in the U.S. has been shrinking.

* % of net asset value (NAV) plus unfunded commitments

Source: Hamilton Lane, data as of July 2018.

As the chart illustrates, investments in private markets have grown from approximately $0.5 trillion in 1999, to approximately $4.9 trillion through March 31, 2018, as investors broaden their exposure to private markets in order to capture sufficient exposure to the economy. Although this data reflects that private-market investments are still a relatively small part of the total investable universe, when compared to public markets at $45 trillion, the figures actually understate the total private-capital market size. This is because they don’t reflect so-called shadow capital, which comprises limited partner commitments to separate accounts, co-investments or direct investments—data which is difficult to track. Regardless, there is no denying that private markets are growing.

What about private debt?

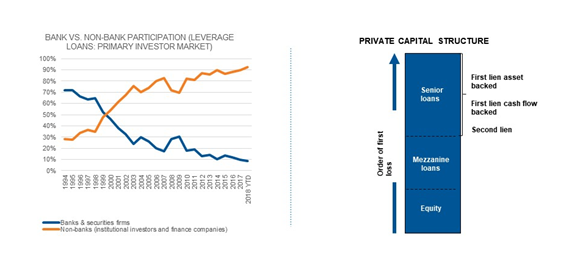

Another macro trend over the last 20 years is that banks have been providing a smaller proportion of loans, whether for balance-sheet retrenchment, regulatory compliance or other factors. As banks have pulled back from lending, the gap has been filled by private lenders, and institutional investors have allocated more assets to private debt.

The chart below shows that the percentage of banks (the orange line) now represents just 9% of the leveraged loan market, while private lenders have been filling the gap.

Source: Chart is sourced from S&P Global Market Intelligence, “Leveraged commentary and data”, September 2018.

Why are institutions allocating to private debt? There are several reasons, but chief among them are:

- They serve as an alternative to investments in banks (particularly those which have non-performing loans);

- Some investors view private debt as having similar risk as some other fixed-income assets, but with the benefit of higher yield potential; and

- Some investors view private debt as a less risky way to play private equity exposure.

On the right side of the chart is a simple schematic of the private capital stack. Just as with public investments, equities are riskier than bonds. Mezzanine loans are debt—less risky than equities, but subordinate to senior loans (which is why they’re sometimes referred to as junior debt). Senior loans are the least risky—but not all senior loans are equal. The level of security (if any), coupled with your place in the queue in the event of economic slowdown, corporate distress or bankruptcy, makes a significant difference to the risk and return.

A critical element of investing in private debt is the manager’s ability to evaluate the credit risk of the borrower. Lenders tend to focus on particular sectors, and particular slices, of the debt universe.

For example, some lend based on analysis of a respective company’s cash flows; others only make loans secured by physical assets of the company. Some lenders are generalists, others focus on particular sectors where they have expertise. For example, lending to food-retail franchises, or enterprise software companies, or the commercial real estate sector, all have completely different risk factors. The critical point is this: private debt is very specialized, and it’s paramount to know what you’re investing in, as well as the related risks and returns.

Manager and asset selection matters

Manager selection is always important and is critical to success. It is especially important in private markets because of the investment, operational and legal due diligence complexities and longer-term nature of the investments.

Investors should be aware that there has historically been a wide dispersion of returns among private-markets managers. Indeed, the performance differential between the top and bottom quartile managers can sometimes be thousands of basis points.

The bottom line? Before investing in private markets, make sure you have the expertise needed to navigate the asset class’ complexities—or work with an organization that does.