Do you know how to calculate after-tax returns?

With tax season behind most investors, many won’t worry about taxes until April 2020. But focusing on investment taxes all year—not just in April—can make a material difference in successful after-tax outcomes. And when considering investment taxes, how do you measure the impact taxes had on your investment return? How do you calculate after-tax returns?

In my discussion with both advisors and investors, I often see confusion on how to calculate—or worse, no consideration of the tax impact on investors. The process of calculating after-tax returns may seem confusing or onerous at first, but it really is a worthwhile exercise. If you aren’t considering after-tax returns, how can you define successful outcomes?

And 2018 was a year when most U.S. equity investors saw negative returns, yet 86%1 of U.S. equity mutual funds experienced taxable distributions.

To properly calculate an investor client’s after-tax return, an advisor needs to consider the distributions coming from the underlying investments. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll limit this discussion to mutual funds, individual stocks and bonds.

Identify the distribution.

Often investors want to apply the marginal tax rate to an investment’s pre-tax return. That’s not necessarily correct. The after-tax return should focus on the actual distribution and/or realized gain for that year—not the rate of return.

Consider this scenario: If the investment return was through a price-change in the underlying security (either appreciation or deprecation) without an actual distribution or realized gain, no tax impacts are attributable unless the security is sold. Deferring gain realization can have a powerful compounding effect over time. So be sure to identify the amount of the distribution first.

Or, if the investment had a negative return AND had a distribution (capital gain or dividend), this distribution likely only made the negative return worse.

Mutual funds can do some of the work for you.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires all fund companies to publish after-tax returns for their funds. They’re just not always easy to find. At Russell Investments, we publish that information daily for many of our ’40 Act2 funds on russellinvesments.com. You can also use a third-party vendor like Morningstar for after-tax return calculations. Both Russell Investments and Morningstar use the methodology that the SEC mandates, which takes the most conservative position by assuming the highest marginal rate applied to the fund’s distributions.

This works if your client is in the top tax bracket. (For example: taxable income > $612,350 for short-term gains and taxable income > $488,850 for long-term capital gains if the filing status is married filing jointly in 2019.) But there is no accommodation for state income taxes. The state tax is an additional tax drag and can be meaningful for those in the higher tax states.

If your client is in the top bracket and invests only in mutual funds, you have a head start on trying to calculate the after-tax return of the total portfolio. And that’s the number that really matters for taxable investments.

Do the prep

Identifying the following numbers, among others, can be a beneficial step in preparing to calculate a client’s after-tax return:

- What is the amount of your client’s actual distribution during the calendar year?

- Where are the distribution amounts located?

- What is the character of the distribution? Was it interest income? Qualified or non-qualified dividends? Long-term capital gains (LTCG) or short-term capital gains (STCG)?

- What is your client’s specific tax rate? Be sure to consider:

- Marginal federal and state tax rates (the tax on next dollar earned) for gains taxed as ordinary income. STCG and gains from other assets are taxed at the marginal rate.

- Medicare tax. The 3.8% Medicare tax for the Affordable Care Act remains. This is tied to investment income (interest, dividends and capital gain distributions) for clients with modified adjusted gross income high enough to cross the threshold. This remains at $250,000 for married filing jointly status and is not indexed for inflation (meaning more people will get to pay this tax going forward).

- Does the client have capital losses outside the portfolio you managed? Or a capital loss carry-forward to offset against distributed gains? If so, it might be possible to use these to offset the current distribution.

Do the math

Once you’ve done your prep work, it’s a straightforward calculation to determine the after-tax return. Just follow these steps;

- Apply the correct tax rate to the calendar year distribution. Use the top marginal rate for STCG, taxable interest, non-qualified dividends or other items treated as ordinary income. Use the LTCG rate for qualified dividends and capital gains held greater than one year. Remember that it’s not just the capital gain distributions, but also the taxes tied to dividends.And taxes apply even if distributions are reinvested.

- Do the calculation*:

(ending market value – tax paid) – (beginning market value)

(beginning market value)

The result approximates the client’s after-tax return.

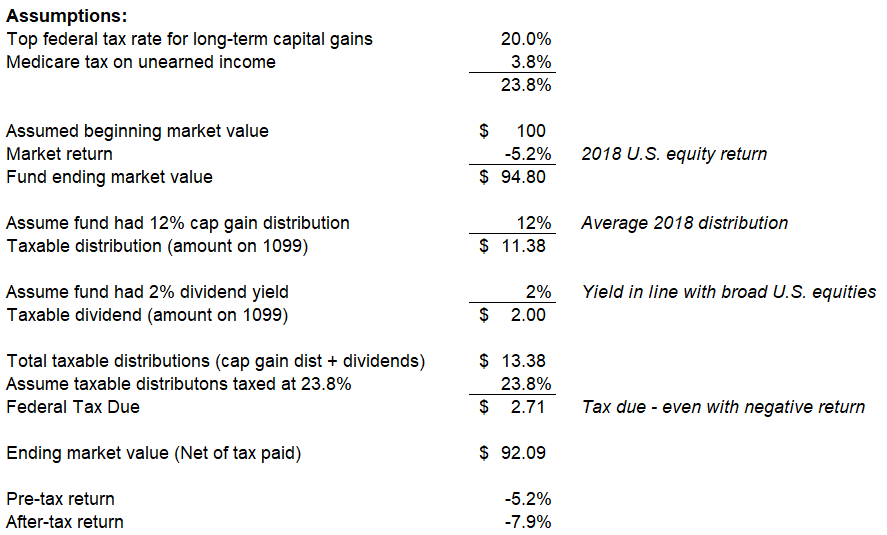

It may help to look at an example. Here is the math for a hypothetical fund that depreciated in line with the U.S. equity market in 2018. In this case, gains and dividends are treated as long-term and taxed as long-term capital gains.

Click to enlarge

*Note: The ending market value in this equation assumes distribution was reinvested.

Not only was the hypothetical fund down for the year, but when you consider taxes, it was down 2.7% more than the reported pre-tax return. (The ending market value in this equation assumes distribution was reinvested.)

Bottom line:

Calculating after-tax returns for your clients is worth the effort. How else can you determine whether there may be opportunities to employ strategies to help maximize your clients’ after-tax wealth?

This is powerful information to know and share in client reviews. Because who cares the most about this topic? It’s high net-worth investors. And who couldn’t use a few more of those as clients? Remind your clients it’s not what they make, it’s what they get to keep!

This article first appeared in InvestmentNews on May 1, 2019.

1 Based on Russell Investments’ broad look across all products within the Morningstar U.S. equity universes (large, small, mid, active, passive, ETFs, etc.) Percentage = calendar-year cap gain distributions / year-end NAV. Includes all share classes. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly. Returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment.

2 The Investment Company Act of 1940 was created through an act of Congress to require investment company registration and regulate the product offerings issued by investment companies in the public market. It primarily targets publicly traded retail investment products.