January U.S. CPI: A small setback for the immaculate disinflation

Executive summary:

- The consumer price index (CPI) for January showed that core inflation held steady at a rate of 3.9% last month, a small setback in a trend of moderating inflation in the U.S.

- Healing in global supply chains and a rebalancing of the U.S. labor market have helped to dramatically tame inflation over the past year.

- We're slightly cautious on the market outlook, as most positive inflation news has already been priced in and recession risks still look elevated. For long-term investors, we believe it’s best to stay disciplined and stick close to your strategic asset allocation.

Inflation was a key concern for investors in 2022. Transitions away from high inflation periods have been difficult for central bankers to achieve without slowing down the cycle, or worse, tipping the economy over into recession. Into this checkered history, the recent run of inflation news has been fantastic, on balance, with six of the last seven core PCE (personal consumer expenditures) inflation readings coming in at/below the Federal Reserve’s 2% goal.

This morning’s U.S. CPI report was a small setback in a broader trend towards moderating inflationary pressures. Core CPI increased 0.39% month-on-month into consensus expectations for a 0.28% increase. This was not an earth-shaking surprise, but it was disappointing. Digging another layer down, owners' equivalent rent was particularly strong, but this category is likely to gradually moderate going forward as timelier measures of rents and home prices have already converged back to pre-COVID norms. Other volatile categories like hotels and airfares were stronger in January as well and don’t carry much signal for the outlook. We’ll look to the producer price data later this week to round out the picture, but so far it looks like core PCE inflation is tracking a smaller 0.29% increase, which would nudge the 6-month annualized figures up to 2.2%—still within spitting distance of the Fed’s inflation target.

In the rest of this article we zoom out to unpack the trend of moderating U.S. inflation with an eye toward the outlook, key risks, and implications for monetary policy and markets.

The immaculate disinflation

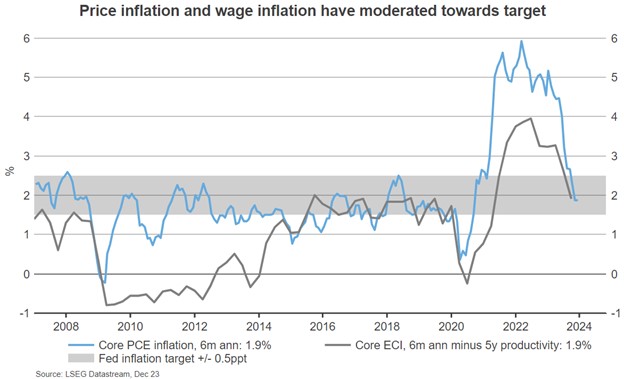

At the end of 2022, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) forecasted real GDP (gross domestic product) growth of 0.5% and core PCE inflation of 3.5% for the year ahead—i.e., a soft landing for the economy with a sticky inflation problem. Fast forward 12 months, and 2023 ended up being a Goldilocks year for the United States. Economic growth surprised sharply to the upside (3.1%) and inflation surprised to the downside (3.2%). The progress on inflation looks even better if we zoom in on what has happened over the last six months. Here, both price inflation (blue) and wage inflation (gray) have fallen back to target-consistent levels. There are open questions around the durability of this progress—that we’ll discuss in the next section—but it has been remarkable to see.

Above-trend growth with moderating inflation is a rare constellation of outcomes which requires favorable supply-side developments. We’ve had that, in spades.

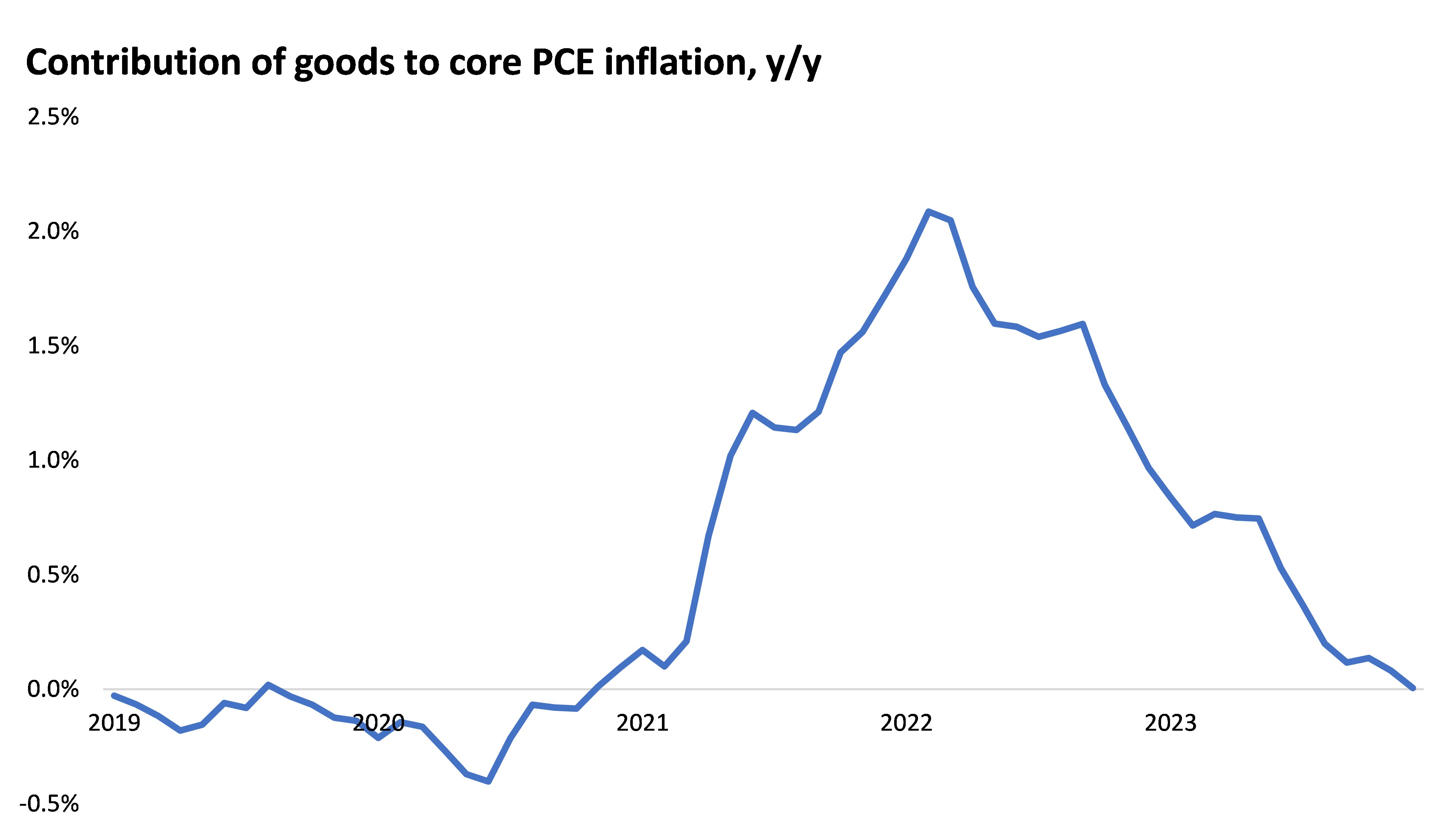

First, global supply chains—which broke down during the COVID-19 factory closures, worker shortages, and surging demand for durable goods—now appears to have largely healed. We estimate that at their peak, core goods prices were adding 2 percentage points to core inflation in the spring of 2022. But as supply chains healed, core goods flipped back into deflation over the last seven months which is the norm for this category in the 25-years leading up to COVID-19. That’s a big swing and expected, albeit welcome, progress.

Furthermore, the labor market—which was very overheated in 2022—has rebalanced in a painless manner thus far. This adjustment has come through a decline in job openings without a commensurate rise in layoffs and a surprising recovery in labor supply. Three key developments have supported labor supply:

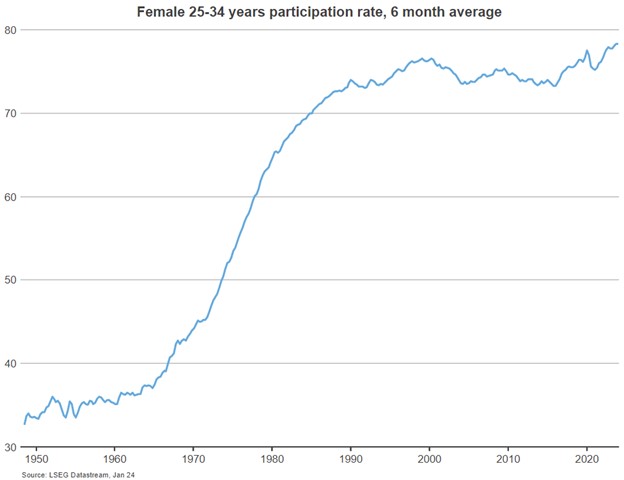

- The participation rate of young women in the labor market has surged to an all-time high. Recent research suggests greater access to hybrid work arrangements is one factor behind this phenomenon, allowing more women with families to remain engaged with their work in a way that was not previously possible.

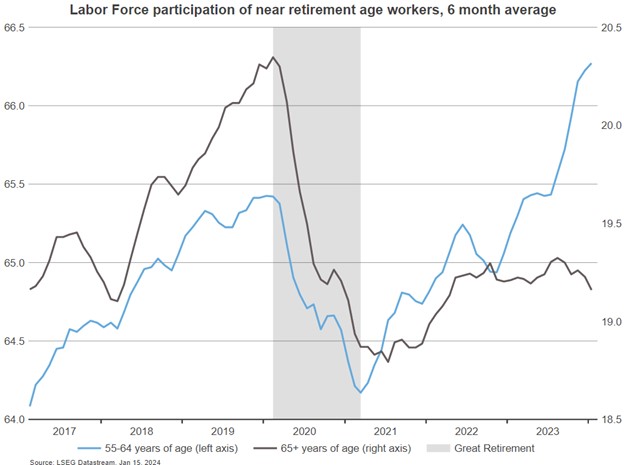

- Another positive surprise came from the near-retirement cohort of workers aged 55-64. The COVID health scare, combined with the strength in housing and asset markets in 2020-2021, created a Great Retirement where many near-retirement individuals—sitting on a solid nest egg—left the labor market early (blue line, shaded area). But participation for 55–64-year-olds has now recovered sharply, surprising many forecasters.

- Finally, net immigration flows have recovered to their strongest levels in the last quarter century, following a dip during the Trump administration which then persisted during the COVID-19 disruptions early in Biden’s first term.

We can’t bank on these favorable supply-side tailwinds continuing in perpetuity, but even if they dissipate, they were still critical in pushing the U.S. economy back into better balance in a painless manner and contributing to the Goldilocks outcome of healthy growth and moderating inflation in 2023.

Pressure building on the Fed to cut interest rates

Concern over high inflation becoming entrenched in the U.S. economy was the primary reason the Federal Reserve (Fed) aggressively pivoted monetary policy toward a restrictive stance in 2022 and 2023. As price and wage inflation data now fall back towards their 2% price stability goal, pressure is building for the FOMC to cut interest rates back down to a more normal, or neutral, posture.

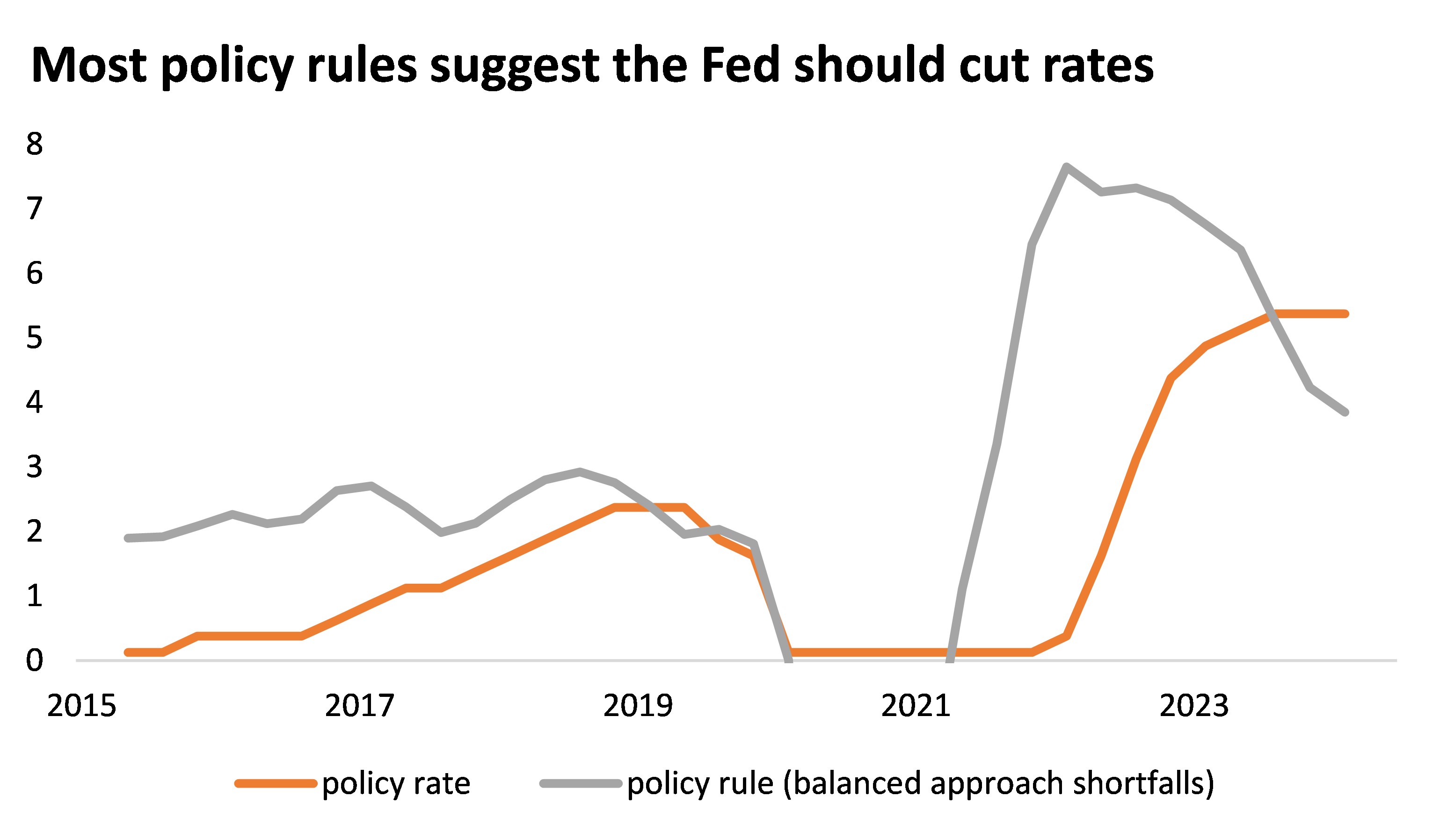

Guessing exactly when the Fed will cut is a bit of a sideshow. My best guesstimate is May. But that’s Chair Jerome Powell’s decision to make and I don’t have any special insight into his thinking. What we can and do analyze is what the Fed should be doing via its own policy rules. These aren’t prescriptions but rather useful guides for setting interest rates.

Following its most recent strategic review, the Fed flagged the “balanced approach (shortfalls)” rule as a simple way to illustrate the Committee’s focus and objectives. What does that rule say the Fed should do right now? Cut interest rates by 150 basis points (gray minus orange). Again, this is just a guide. The Fed won’t deliver a 150-basis-point cut in March, but the pressure is building on them to pivot in this direction, soon.

Risks

There are two important risks to the inflation outlook. First, shipping issues in the Red Sea and Panama Canal are causing another surge in transportation costs. For now a rough read of the passthrough onto core inflation looks manageable—at 0.2 percentage points per the observed increase in the Harpex Shipping Index so far. But to state the obvious, the longer this drags on, the worse it will get. Importantly, though, the situation looks less dire than many investors might think back to from COVID. Factories are not shut down, worker shortages at ports are not as extreme, captains are allowed to disembark at port, and the demand for goods has come off the boil. But it’s clearly a risk to monitor given the unpredictable nature of geopolitics.

Second, and more fundamentally, economic growth could remain robust and lead to a stickier or even reaccelerating inflation problem. This is not our central scenario for 2024 but clearly is in the realm of possibility. As hopes of a soft landing for the economy build, we see early signs that CEO confidence is improving, that capital expenditures (CapEx) intentions are pickup up from low levels, and a decline in interest rates—if sustained—could reinvigorate demand for housing and other interest-sensitive spending items like consumer durables. This is not the economic outlook that we were bullish about in the spring of 2020 with a long runway of non-inflationary growth. Stronger growth into capacity constraints comes at the risk of a stickier inflation problem, slower rate cuts, and higher interest rates that could challenge U.S. equity market valuation multiples.

Markets

Risk markets like equity and credit are priced for the current regime of strong growth and disinflation to persist. Our proprietary index of equity market psychology shows a lot of optimism in current prices (a cautious signal for the outlook). Furthermore, year-ahead recession probabilities extracted from credit markets are more sanguine (20% odds of recession) than our own view (40%).

We believe U.S. Treasuries, by contrast, offer reasonable value. Starting yields look attractive, trading 2-3 percentage points above expected inflation across the yield curve. In addition, current federal funds futures pricing for 4 to 5 rate cuts this year looks reasonable to us.

In summary, our research leans slightly cautious here at the turn into spring. For long-term investors, staying invested and sticking to your strategic plan and asset allocation looks appropriate. Ultimately, while there has been important good news recently, it’s largely already baked into the price.