Checking in on the ‘cult of equities’

“For better or worse, then, the U.S. economy probably has to regard the death of equities as a near-permanent condition…” - Newsweek, August 1979.

“The cult of equity is dying. Like a once bright green aspen turning to subtle shades of yellow…” - Bill Gross, October 2012.

“Sell everything except high quality bonds. This is about return of capital, not return on capital. In a crowded hall, exit doors are small...” - Royal Bank of Scotland, 2016.

For decades investors and journalists have written extreme warnings about the long-term return potential for equity markets. At this juncture, it is understandable why similar pronouncements could be made.

Starting their careers in the 90s, Gen Xers have now experienced three deep recessions (2001, 2008, 2020), and in each one an accompanying stock market decline typically exceeding 30%. Those who invested their money in global equities on Jan. 1, 2000 only have a 4.1% annualized return to show for it by the end of March 2020, with a high level of volatility throughout. This experience has led many investors to question whether equities are worth taking the risk.

The bear case is well known, and the narrative tends to focus on the next 12-24 months

The most contemporary argument pertains to the structural impairment to the economy resulting from COVID-19 lockdown measures. It is true, certain industries will likely never recover completely. New social distancing behaviors, plus permanent consumer behavioral changes, will likely make certain businesses unviable in the new world. In the near term, companies are going to go bankrupt and there will be an increase in corporate defaults.

The coronavirus also dramatically accelerated forces that were already in effect concerning the way our increasingly service-orientated economy operates. For those of us working in offices over the last decade, we have seen an increase in hot-desking, working from home and a rise in flexible short-term office space (for example, WeWork and Regus). The government-imposed lockdowns have compelled service-based companies to rapidly level-up virtual office functionality, which by most accounts have demonstrably been a success without much of a discernible loss in productivity. A recent Deutsche Bank survey of 450 institutional investors found that 52% of participants plan to continue working from home two or more days per week, and 72% think that they are able to achieve the same, if not better, level of productivity when working from home. The ramifications of this culture shift will likely negatively impact commercial real estate and areas of the economy that are geared around a service-based economy with a physical presence.

Nonetheless, the economy should overcome these challenges. The modern global economy is a dynamic, transformative force fostering human innovation and driving obsolescence through creative destruction. 25 years ago, the internet didn’t exist. Today, companies whose existence is only enabled through the advent of internet technology make up approximately a quarter of the market capitalization of the S&P500® Index. In hindsight, an increase in working from home and virtual offices may seem to have been the inevitable end-game, as the state of today’s technology means we can have commercial-grade workstations in the comfort of our living rooms. Coronavirus was just the disruptive catalyst for this shift to take place en masse.

The other major critique centers on valuations—namely, that despite a brief correction in the first quarter of this year, equity valuations are still elevated on a historical basis. Global equities currently trade on a multiple of 17.5 times next-year earnings (the 20-year historical average is 14). However, this is a function of global equities being considerably skewed towards U.S. equities—a result of a decade of outperformance. The U.S. currently represents 60% of the global stock market—this figure was close to 40% in 2009. Looking beyond the construct of global equities we can observe that other equity markets exhibit very reasonable valuations relative to their longer-term averages.

Other objections are a potential slew of political and geopolitical risk factors (the China-U.S. fractious relationship, risk of another eurozone crisis and a second wave of COVID-19). We can’t reasonably ascribe probabilities, let alone estimate the magnitude of their impact on financial assets, but we do know that politically engendered risk themes have been pervasive throughout history. In the 1940s, it was World War II, in the 1960s, it was the Vietnam War, in the 1980s, it was the Cold War and an oil shock, and in the 1990s and 2000s there have been multiple protracted entanglements as well as the War on Terror. Our view is that just like in the television series "24" there will not be an episode without drama or political intrigue—and there will always be a reason not to invest. Ultimately these reasons just represent bricks in the contiguous wall of worry that investors need to scale.

But the bull case is long term and structural in nature

Where can you go to achieve returns?

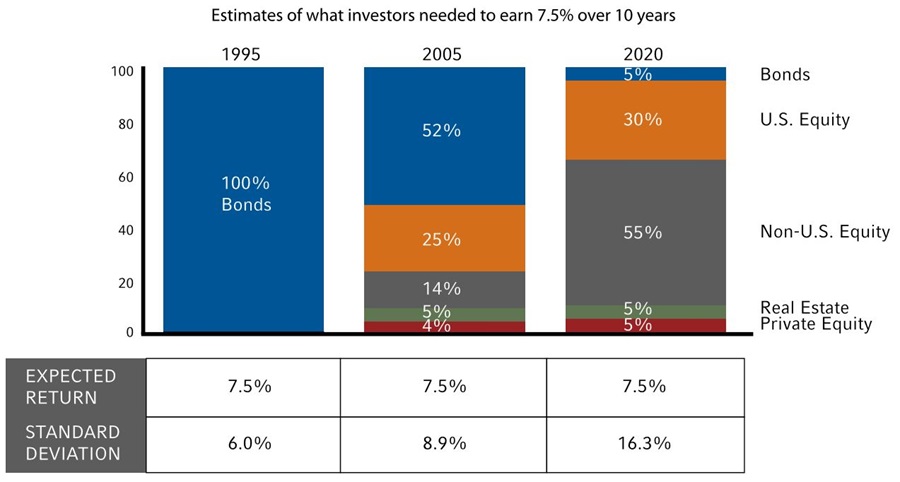

Unfortunately, in an environment of financial repression with interest rates in developed countries pegged at zero for the foreseeable future, there is a shortage of asset classes that can achieve required return objectives. The chart below shows the evolution of available returns for investors based on forecasting assumptions that consider prevailing cash rates, bond yields and equity valuations. The common thread is that investors are being forced to take ever-increasing levels of risk, as measured by standard deviation, in order to achieve a constant return outcome.

Source: Russell Investments' March 2020 Asset Class Strategic Planning Forecasts and The Wall Street Journal, May 31, 2016.

Equities are almost the only viable asset class to achieve return objectives and this applies to all classes of investor: employees investing to achieve retirement goals, pension managers aiming to meet absolute return objectives and insurance companies seeking to generate returns to meet cash-flow commitments to policyholders. On the latter point, regulators—acknowledging the scarcity of feasible asset classes—are already clearing obstacles to investing in equities. In 2019, the European Commission published a draft amendment to Solvency II regulation that will reduce the capital charge (collateral held in the event of a shock) required by European Insurance companies for holding long-term equity investment from 40% to 22%.1

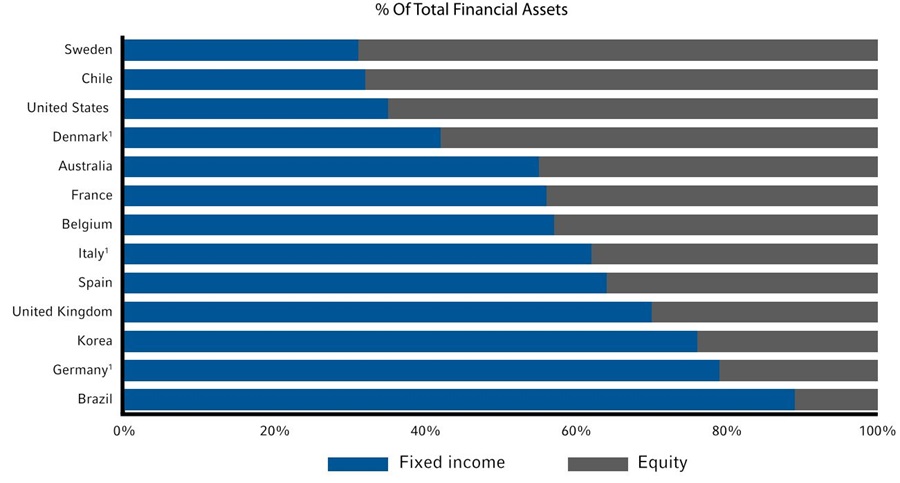

Taking a closer look at the asset allocation of households at country level, we can see that the U.S. composition of financial assets is already showing a skew toward equity. However, there is enormous latent potential for a broad asset allocation switch from bonds to equity in other countries, likely catalyzed by the gradual recognition of the current inadequacy of many portfolio configurations to achieve desired return outcomes.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Oliver Wyman

We have spoken about changing the composition of the pie from bonds to equity, but the pie itself is also projected to grow. As emerging-market nations continue to see their middle class evolve, they will likely follow the blueprint of major developed countries—meaning deeper and more liquid capital markets, a burgeoning pension industry and rapidly growing assets under management. India is a great example of this. In the last ten years, the Indian Mutual Fund industry has grown by 570%, or an annual CAGR of 20.9%.2

Collectively, these forces create huge potential demand for equities, serving as a bullish tailwind simply because there are limited viable alternatives.

The evolving pension landscape

As lifespans increase and corporations come to the realization that they can’t collectively afford to finance these now elongated retirements, employers have been switching from paying out a lump sum upon retirement based on the number of years worked and the employees’ final salary (defined benefit or DB plans) to paying employees on a routine cycle in line with payroll (defined contribution or DC plans). The net impact is that employers no longer have to warehouse these future obligations on their balance sheet for the duration of their employee’s tenure, and instead are effectively transferring both current and future investment risk to employees who have discretion as to how their future retirement contributions are invested.

While the DB plans still account for the bulk of $40.1 trillion explicitly saved for retirement globally, many DB plans are closing or have been closed to new members.3 Pensions consultant LCP recently reported that in 1993 virtually all FTSE 100 companies offered traditional final salary (defined benefit) plans to new employees. By 2018, not a single one did.4

The entire approach to risk tasking is changing as a consequence. Companies with the obligation to finance employee retirements per a DB plan, particularly those that are underfunded, have tended to be conservative in taking risk. Their focus tends to favor risk mitigation, at the expense of return generation. The 2019 Aon Asset Allocation survey shows that DB pension plans in Europe and the UK on average tend to hold 25% of plan assets in equities, with the remainder predominantly in bonds.5

Contrast this with individual employees that, on average, individually have decades until retirement, have the impetus of their monthly pension contribution (and can, therefore, dollar/pound cost average) and the general compulsion to undertake a higher degree of risk in order to finance their aspirational standard of living during retirement. The ongoing growth in DC plans, and the significant change in risk appetite that it entails, will likely drive demand for asset classes that can actually deliver on required return outcomes.

De-equitisation: While equity demand is increasing, supply is shrinking

Markets are shrinking. Companies are buying more of their own shares than they are issuing via IPOs and secondary capital raising. The mechanism is known as buybacks, where debt is issued at low interest rates to finance the purchase of outstanding shares.

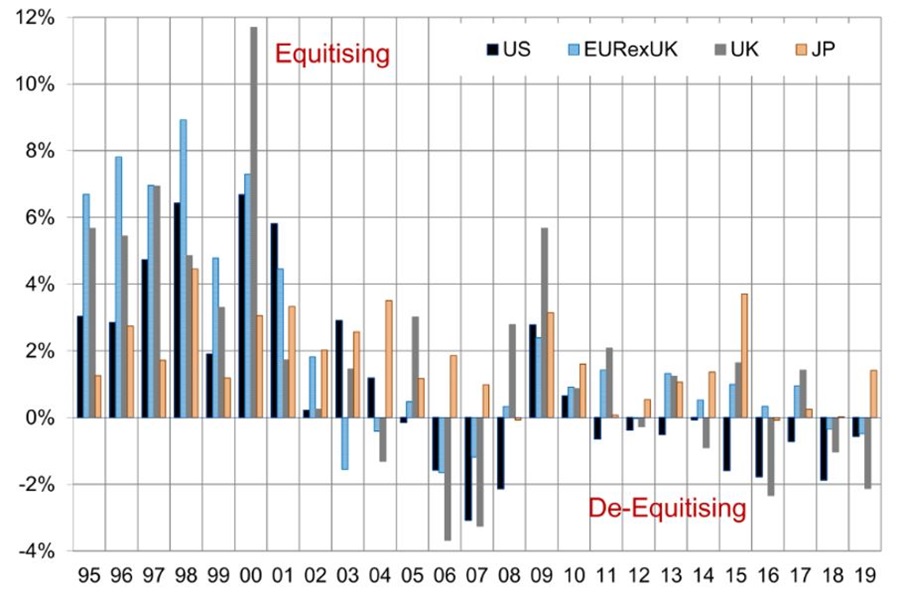

The below chart illustrates the reduction in the net outstanding shares over the last decade, predominantly in the U.S., but increasingly in the UK and Europe in recent years, as buybacks outpace share issuance.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Citi Research, Datastream.

(Note: De-equitising refers to a shrinking of outstanding stocks, typically due to share buybacks. Equitising refers to a net increase in stocks where companies issue equity to fund operations and expand).

Buybacks often constitute a shocking misallocation of resources, which deprives balance sheets of a margin of safety during periods of stress. As a group, the six major U.S. airlines spent 96% of their free cash flow on stock buybacks over the past 10 full years through 2019, before approaching the government in March for a bailout.6 For this reason among others, corporate buybacks have recently attracted the attention and ire of politicians. Nevertheless, many companies are still retaining their buyback programs. In May 2020, Apple announced U.S. $50 billion of buybacks for the full calendar year, equating to approximately 4% of its market capitalization at the time.

One of the main reasons behind the rise of buybacks in recent years is the lack of confidence in future economic conditions—i.e., the risk that a new venture or capital expenditure may not be sufficiently rewarded if the economy started to deteriorate. In a post-COVID world, this economic uncertainty has only increased. Consequently, even if politicians are successful in curtailing buybacks, there is no guarantee that this money will be spent on capital expenditure or research and development. Instead, these companies will likely just buy the shares of other companies (mergers and acquisitions), rather than their own. This all speaks to an ongoing shrinkage of equity markets—a reduction of supply at a time when demand is projected to increase.

The bottom line

The struggle between bullish and bearish forces are a permanent feature of financial markets. Regardless of which force prevails, we can confidently say that financial markets will likely experience more frequent periods of volatility and episodic drawdowns going forward. There have never been as many market participants, information has never been disseminated so quickly and the obstacles to trading frequency have been essentially removed with the erosion of brokerage commissions. These factors will likely make the stock market more erratic when observed over shorter time periods.

However, the primary intent of this blog post is to encourage investors to refocus their time horizon. Instead of narrowly looking at the political and economic issues of the day as a reason to avoid equity investment, we believe investors should consider longer-term themes which are likely to exert much more influence. The empowerment of the individual in discretionary DC pension investing, the growing global middle class and the general trend of higher aspirational wealth will collide head-on with a shrinking cohort of asset classes that can realistically deliver on these return outcomes. The outcome of this collision will likely manifest in the form of higher future equity prices.

1 Source https://www.debevoise.com/insights/publications/2019/05/european-commission-incentivises

2 Source http://content.icicidirect.com/mailimages/IDirect_IndustryAMC_IC.pdf

3 Source BNY Mellon paper: "Defined contribution matching investments and liquidity"

4 Source https://theconversation.com/britains-great-pension-robbery-why-the-defined-benefits-gold-standard-is-a-luxury-of-the-past-100844

5 Source https://info.mercer.com/rs/521-DEV-513/images/ie-2019-european-asset-allocation-survey-2019.pdf

6 Source https://www.marketwatch.com/story/airlines-and-boeing-want-a-bailout-but-look-how-much-theyve-spent-on-stock-buybacks-2020-03-18