Confessions of a portfolio manager

Having been through several bear markets, Senior Portfolio Manager David Vickers has his fair share of scars. As such, he openly admits to being a cautious investor. Today, David prepares for the future by looking beyond simply beating the benchmark—he seeks to mitigate drawdowns and exploit the power of compounding.

Confession #1: I am beset by behavioral bias

I am, as we all are, shaped by my own experience. And today, I have more than my fair share of scars!

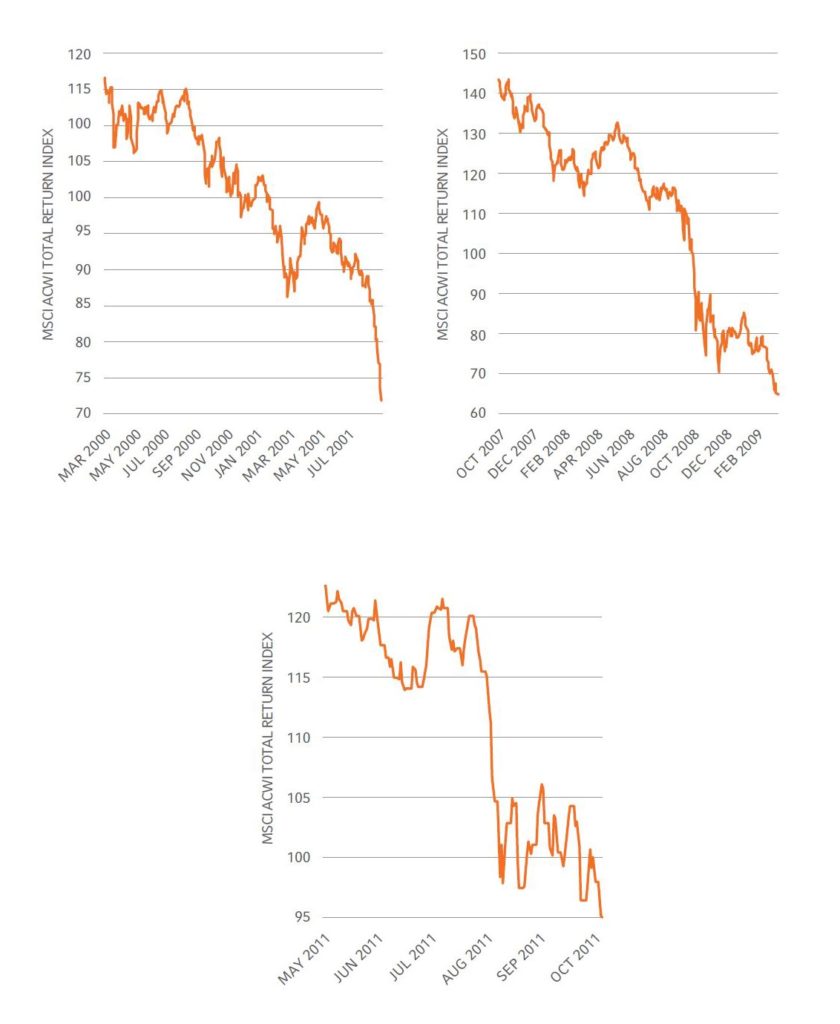

Joining the industry in 1999, I was very quickly witness to one of the most spectacular crashes in history where the S&P 500® Index fell 49.1% by 2002. Fast forward six years and we hit the Global Financial Crash of ’08 where we saw the S&P 500® Index down 56.4%. Then in 2011 we saw a succession of European crises.

Shaped by my experience

Source: MSCI ACWI (All Country World Index), Bloomberg. Index returns represent past performance, are not a guarantee of future performance, and are not indicative of any specific investment. Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly.

Hurrah, my losses are less than my peers' and the benchmark …

Living through these experiences has played a large part in shaping my career, and my behavioral bias. I now openly admit to being an inherently cautious investor. I know that I need to take risks to get return, but witnessing the destructive power of losing money has influenced me. This was reinforced during the early part of my career when I ran money for family offices and endowments—putting a very real edge to the consequences of losing money. When grants aren’t made or scholarships not awarded, the loss suddenly becomes very human and tangible.

In fact, during 2008 it was my mom who also helped influence a turning point in my investment attitude. Not a part of the finance industry (she’s a teacher), my mother took me aside during Christmas dinner and told me that she’d seen my performance and was worried about my prospects. I explained that yes, I had lost money, but that I’d lost a lot less than others, including the benchmark. And this, I explained to her, was considered a relative success. Mom shrugged her head and said that it couldn’t be right, because the bottom line was that I had lost money—and how could that be a success?

This resonated with me and so I began to re-evaluate what success really means.

So, what does investment success really mean?

Ultimately, success for me is achieving my clients’ required rate of return—and a crucial part of this is preserving the real value of capital. That’s why today I aim to look beyond simply beating the benchmark because, what if the benchmark is down? So what if I’ve lost less money than the benchmark, I’ve still lost money.

I now know what type of money manager I strive to be. I want to be one who makes money in 2008 and between 2000-2002, for example, rather than someone who simply makes more money than others in an upswing. To borrow and then misquote a phrase from Warren Buffet, when the tide goes out I don’t want to be exposed as an investor without swimming shorts on!

I want to mitigate drawdowns and exploit the power of compounding. But how do I, or indeed should I, look to conquer my desire to protect value and essentially be contrarian? On the face of it, drawdown mitigation sounds like a noble pursuit—but digging a little deeper, the answer is not quite as clear, or as easy. Being contrarian is only good if you are contrarian and right! Timing is everything. Preservation can’t be pursued at all costs; optimism has its place too. After all, markets do tend to trend up more than down.

We all suffer from investment bias, but a strong process always prevails

As investors, we all suffer from biases, whether that’s institutional conservatism, confirmation bias, anchoring overconfidence, or regret risk, for example (and there are a whole host of others). But many of these can be reduced by a strong process. There are a number of things one can do to help utilize these to your advantage—but the first step is to recognize, accept and openly welcome your biases.

At Russell Investments, fund managers work very closely with the investment strategists to challenge and debate one another—but importantly, we all report in separately to the chief investment officer, so it avoids the risk of seniority trumping real debate. In a similar vein, we also deliberately seek out challenge from outside the firm. This helps us avoid groupthink, but also provides impartial challenge to our views. We take making decisions seriously. Sometimes it’s the decisions you choose NOT to make that count more than the decisions you do make.

On a more personal level, I keep a diary. It lists what we didn’t trade and what we did. It lists why, what led to that decision, and what the prevailing conditions were, i.e., was the market down, up, etc. I also document how I feel at different points in time (this records my regret risk) and what I might do under future scenarios. The diary helps me make rational decisions during irrational times, and it helps me to mitigate the destructive force of behavioral bias.

Honesty is the best policy, really

There isn’t an equation to continuously successful investing, but honest information from the past does help us prepare portfolios for the future. When you review your decisions honestly over the following quarters, you can identify your behavioral biases, isolate them and behave truly dynamically. My investment diary helps highlight these biases, and reminds me when to take risks to encourage returns. Knowing your biases and weeding them out is a huge step to increasing the probability of achieving your objectives.

Learn about how Russell Investments manages the downside.