Is the corporate bond market overheating? Look at the lenders.

Recently, a growing number of investors and market commentators have been advocating for caution in credit lending—rightfully so, in my opinion. However, despite the publicity this has received in the press, it appears that little has actually been done to clamp down on aggressive lending. Perhaps this should not be surprising since in practice, lending is done from the bottom up.

Viewed at the individual borrower level, the plethora of recent deals may not look so bad, so why pass? After all, in many cases, company fundamentals—boosted by strong earnings—are solid and it stands to reason that many businesses may believe they can probably handle additional debt based on the current economic conditions.

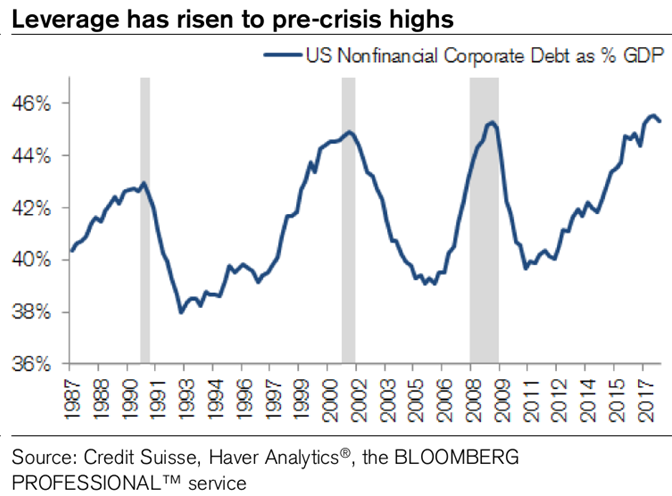

We believe the trouble with this comes when everyone takes advantage of this opportunity. Then the total debt levels in the economy increase rapidly. We see this as highly problematic. Why? Rising corporate debt breeds instability, as any hiccup in the economy or markets can increasingly reverberate throughout corporate America and the real economy.

This is why we believe investors are wrong to focus on the state of borrowers in assessing the credit cycle. At Russell Investments, we prefer to focus instead on the state of the lenders, as this historically has been a much better indicator when assessing the market cycle. Zeroing in on this, we see many indicators that are shifting from caution to outright warning status.

Corporate lending: Aggregate vs. composition

There are two main perspectives we use in assessing corporate lending: aggregate amounts and composition. Aggregate debt, at least as a percentage of the economy, is not limitless, as it may eventually breed the aforementioned instability that can knock over the cycle and lead to painfully forced deleveraging. Certainly, changes in the economy and the composition of lending can alter what levels ultimately lead to instability, but in recent cycles, corporate debt levels have tended to peak at similar levels as a percentage of GDP (gross domestic product). We believe investors who ignore this fact are ignoring history at their own peril.

On the composition front, the signals appear mixed on the surface, but become more sinister as we dig deeper. What’s going on?

For starters, supply from the traditional high-yield bond market has actually been rather low given how well the economy has been going. We take this as a sign of some discipline in the market—and, at first glance, perhaps a decent reason to be bullish on this end. Unfortunately, this bullish assessment only goes skin deep. While lower-quality companies are not issuing many high-yield bonds, that doesn’t mean they aren’t levering up late in the cycle. Below investment-grade companies are instead issuing a lot of high yield loans. Why? Because it’s predominately where lenders are seeing the most demand. Consequently, they’re offering some of the most generous terms to some of the riskiest companies.

While loans offer seniority over bonds in the event of defaults, from a lender’s perspective, we believe their advantages start to get whittled away when one considers that today’s new-issue market is increasingly covenant-lite and coming in the form of second liens or unitranche loans with no bonds behind them. Furthermore, the lenders doing the underwriting are largely doing so via collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), which means they are now able to pass on much of the investment risk to others, rather than bear the full responsibility from the loans they make happen. Indeed, there tends to be far less transparency in the loan market than in the bond market. We see this as all the more concerning, as the loan market has now grown to be even larger than the high-yield (junk) bond market for the first time since the global financial crisis.

What’s driving the booming quantity of lending?

When we look at where most of this new debt is coming from, the large majority is originating from investment-grade-rated companies. Why? Presumably, these companies can handle the additional debt better—perhaps meaning that the credit market is actually allocating debt a bit more efficiently and could safely sustain higher aggregate debt levels. While we believe there is some truth here, we also believe that this is starting to reach a limit—if it has not already. As you can see below, leverage in the investment-grade market is at an all-time high for the past 25 years.

How might this impact investors?

Normally, borrower information such as this is less than useful, as it tends to lag market movements. That’s because leverage usually spikes due to a collapse in earnings, not because companies are taking out more debt. Once the market crashes, of course, it’s too late for investors at that point. Today, though, borrowers truly have taken out more debt to reach these all-time leverage levels—and lenders seem happy to allow it.

This ratio is all the more outstanding when we consider that corporate profits are at all-time highs rather than cyclical lows. From our vantage point, there are only two ways for this leverage multiple to correct itself back to more normal levels:

- Increasing or sustained profitability that is used to pay down debt rather than become invested further, or used to reward shareholders.

- Defaults and debt restructurings.

In previous times, when leverage peaked, the first option was typically a very plausible solution, as earnings were quite low and there was ample room for profit growth. Given how different things are this time around, we believe it strains credulity to suggest that either further profit growth or an about-face from CEOs toward less shareholder-friendly use of cash would result in a meaningful reduction in leverage. Unfortunately, that likely leaves us with just the latter option to bear the brunt of the inevitable deleveraging cycle. It goes without saying that this is not a good outcome for credit investors, and certainly not one they are being compensated for.

This last point reminds us of the importance of marrying up all these cyclical dynamics with current valuations. Even in the worst of times, if the valuations are sufficiently compelling, investments could be justified. Thankfully, valuations are quite easy to observe in corporate credit by looking at the average spread or yield over similar duration Treasuries. On this metric, credit today is by no means cheap, and certainly doesn’t compensate for the historically high-leverage investment-grade corporate market.

For now, we believe that greed and the insatiable demand for yield among lenders seems to be winning the day. But, we do not believe this situation will persist. Credit assets have an awfully long way to fall from current valuations when reality does set in and the cycle inevitably rolls over.

Take-home message

One of Russell’s key strategic beliefs in fixed-income is that investors should overweight credit sectors to capture potential higher returns than are available from less credit-sensitive sectors. Truth be told, if we had to rank our strategic beliefs, we’d probably put this one right at the top. However, that does not mean we believe in being overweight all credit sectors, all the time. Selectivity, both in terms of the magnitude of the overweight and what sectors to buy, can be crucial. This is especially true when credit spreads and the compensation investors get for taking default risk are low across the board, and the U.S. Federal Reserve is tightening monetary policy, as is the case today.

Amid this backdrop, our portfolios are currently positioned as cautiously on credit as they have been in the last decade. History tells us the other shoe will drop at some point. The only question is when, not if.