Recession outlook: If China sneezes, could the rest of the world catch a cold?

China is in the process of attempting to restructure its economy from a capital-intensive, investment-led model to a more Western-style, consumption-driven model, without the onset of a recession or crisis. This transition is made all the more difficult by the fact that the Chinese government has an implicit goal in place to try and double GDP (gross domestic product) per capita between 2010 and 2020, and has a lot of control over the economy (meaning the hurdle for intervening is quite low).

It’s worth remembering that China has been through many periods of volatility in the past 20 years alone, starting with the mid-1990s, when a number of state-owned enterprises were shut down. This was followed by the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997, a recapitalization of the banking system in the mid-2000s and global impacts stemming from the Global Financial Crisis.

The big question for the Chinese economy in the short-term is how the trade-off between the escalating trade war and expected Chinese stimulus evolves. Following the recent escalation, we have become a bit more cautious on the outlook for the Chinese economy. Our sense is that 6% GDP growth is still achievable, but the potential for upside has become quite limited.

Challenge #1: The economy is slowing

It’s no secret: The Chinese economy has cooled off considerably over the past year, dragged down by the slowdown in global trade and tariffs imposed by the U.S.

To combat this, the Chinese government has introduced several stimulus measures, including cuts to the reserve requirement ratio for banks, an increase in infrastructure bonds and income tax cuts.

The data flow has been quite choppy since these measures were enacted, with the first round of numbers in March painting a more optimistic picture, followed by a slew of disappointing economic data from April through July that suggests the government’s response has yet to truly have a sizable impact. We continue to cautiously wait for meaningful signs in the data that China’s economy is truly stabilizing.

On the consumer side, however, retail sales continue to grow at very solid rates.1 This has been boosted in large part by the tax cuts, as well as the previous reforms that were implemented to try and encourage consumption and reduce the household savings rate. These include social security, medical care, pension provisions and efforts to expand rural consumption. In particular, the recent Politburo meeting at the end of July reiterated the government’s focus on providing a lift to rural consumption.2

One key development over the past two months, in our opinion, was the takeover of Baoshang Bank by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC). The surprise came with the PBoC noting that “not all of the liabilities would necessarily be guaranteed.”3 We are closely watching the health of other small banks in China and suspect that we may see a few more of these instances, particularly as the government attempts to shift the bulk of lending back to the larger banks. The other related watchpoint to this potential uptick in bank recapitalization is whether provincial governments need to get support from the central government.

Challenge #2: China is showing no signs of backing down on trade

The Chinese government has been quite strident in its responses to the escalation of the trade war by the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump, with the devaluation of the yuan and the cancelling of agricultural purchases the most recent examples. This is likely to remain a headwind for the global economy for some time, with no signs of either side willing to compromise for a deal. Unlike Trump, Chinese President Xi Jinping has no electoral constraint, which means he faces no political repercussions for any steps taken in the conflict.

What would a slowdown in China mean for the rest of the world?

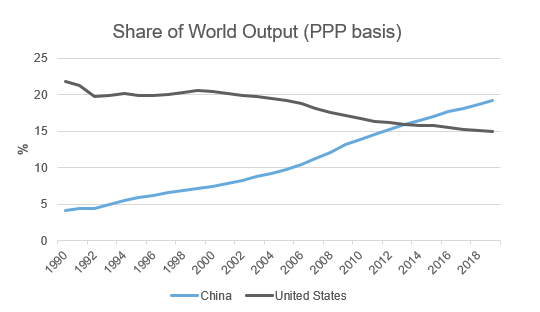

PPP: Purchasing Power Parity. Source: Refinitiv Datastream

Click to enlarge

As shown in the chart above, China has become the largest economy on a purchasing-power parity basis. Additionally, China has moved from running large current account surpluses (i.e., exporting more goods and services than it imports) to coming close to running a current account deficit. Combined with the general shift toward consumption, this suggests that a slowing Chinese economy could be particularly damaging for companies with large supply chains in China.

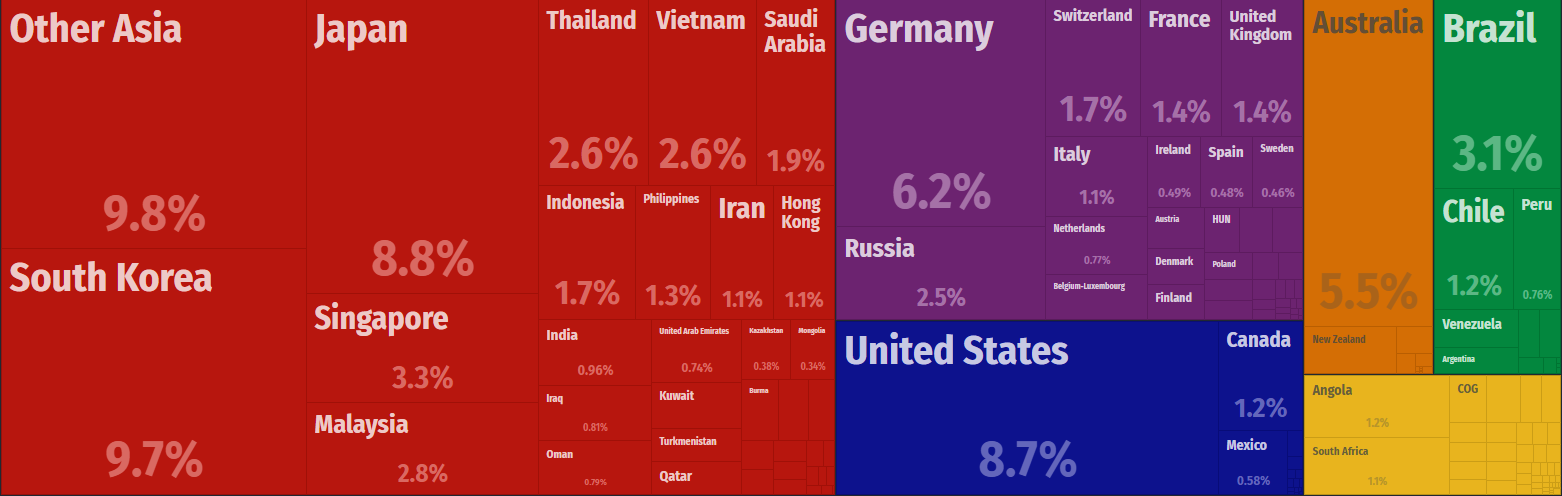

As depicted in the chart below, a slowdown in demand from China could heavily impact other Asian economies, as well as the European economy. Already, we‘ve seen the effects of lessened Chinese demand on German auto production4, although this was exacerbated by new emissions regulations.

However, all things considered, the notion of the global economy catching a cold from China sneezing is probably a bit overblown at the moment, given the fact that it is not a large importer (like the U.S., for example). By one estimate, a 1% GDP shock in China reduces global growth by 0.22%5. By comparison, it has been estimated that a 1% change in U.S. GDP growth would impact other advanced economies by 0.8%6. This is likely to eventually change, though, as China’s transition to a more consumption-based economy continues in coming years. An unhealthy Chinese economy will likely command the attention of global policy makers to a much greater extent within the next decade.

Chart: Origin of China’s imports

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Source: Observatory of Economic Complexity

What could the move away from Chinese manufacturing mean for the global economy?

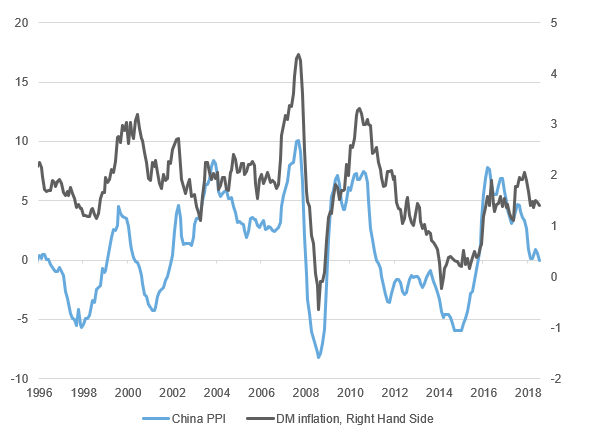

The rise of Chinese manufacturing has been very deflationary for the global economy, as can be seen in the chart below. Why? The large migratory move from rural to urban areas provided a steady stream of cheap labor, which kept costs down.

However, this tailwind is starting to slow, with tightening labor markets beginning to lead to wage growth. Additionally, the uncertainty around the trade war has led to a shift away from Chinese manufacturing, including to some higher-cost countries. On a global scale, this will have the effect of boosting inflation. For instance, Apple is reportedly looking at moving production to Vietnam and India7, Nintendo is looking at Vietnam8 and Foxconn has acquired land-use rights in Vietnam.9 The move to Vietnam is likely to be inflationary, given land is expensive, and factories and warehouses are in short supply. Recruiting trained workers and managers is another challenge.

Click image to enlarge.

Note: DM inflation is developed market inflation, and is calculated as the median of 22 developed countries.

Source: Refinitiv Datastream

The bottom line

In the midst of transforming its economy, China finds itself locked in a bitter trade war with the U.S. However, fiscal stimulus combined with mounting political pressures for the Trump administration as the clock ticks toward 2020 lead us to believe that China’s economy can withstand the short-term risks. The bigger concern, in our opinion, lies further down the road, when the country’s plans for a consumption-based economy come to fruition. A serious setback in the health of the Chinese economy at that juncture may very well send the global economy into a sneezing fit.

1 Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/china/retail-sales-annual

2 Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-07-30/china-s-politburo-vows-action-on-trade-tweaks-economic-policy

3 Source: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/06/28/china-banks-face-cash-crunch-fears-after-authorities-seize-baoshang.html

4 Source: https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Business-trends/China-s-slowdown-unnerves-German-automotive-suppliers

5 Source: Sznajderska (2018), ‘The role of China in the world economy: evidence from a global VAR model’ https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00036846.2018.1527464?scroll=top&needAccess=true&journalCode=raec20

6 Source: Kose, Lakatos, Ohnsorge, Stocker (2017) ‘The global role of the US economy: Linkages, policies and spillovers’ https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/649771486479478785/pdf/WPS7962.pdf

7 Source: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-apple-china-restructuring/apple-explores-moving-15-30-of-production-capacity-from-china-nikkei-idUSKCN1TK0XN

8 Source: https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Companies/Nintendo-to-move-Switch-output-to-Vietnam-as-China-tariffs-loom

9 Source: https://english.vietnamnet.vn/fms/business/216899/iphone-assembler-foxconn-acquires-land-worth-us-16-5-million-in-vietnam-s-industrial-parks.html