Was the September repo spike an anomaly?

The news media, bank executives, the U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed) chairman and even presidential candidates have made remarks about the recent spike in short-term funding rates. What caused the spike and why is it important?

In mid-September, there was a significant spike in the overnight repurchase agreement (repo) rate. The repo rate reflects the level where lenders (e.g., institutional investors and banks) will extend collateralized cash loans to borrowers (e.g., broker-dealers and other market participants) to meet short-term funding needs. The repo market is like the oil that keeps the financial engine running by supplying liquidity through overnight collateralized loans between market participants.

The spike in rates caught many by surprise, despite warnings by the dealer community over declining bank reserves. The consensus view is that a combination of low bank reserves, corporate tax payments and the settlement of the monthly U.S. Treasury auction caused a temporary shortage of cash in the system, forcing repo rates higher.

Timeline & Fed response:

- On Monday, Sept. 16, and continuing through Tuesday, Sept. 17, overnight repo rates, which had been trading around 2.25%, climbed to over 8.5%.

- On Tuesday morning, the New York Fed announced it was adding over $50 billion via overnight repurchase agreements in order to stabilize repo rates. This was the Fed’s first significant use of the temporary repo facility since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

- On both Wednesday and Thursday (Sept. 18-19), the Fed injected an additional $75 billion into the market through new overnight repo operations. These actions largely produced their intended effect with repo rates declining to around 4% by Wednesday morning, Sept. 18.

- On Friday, Sept. 20, the New York Fed announced a series of ongoing overnight and term repo operations through Oct. 10, intended to boost short-term liquidity.

- On Oct. 4, the Fed announced it would extend at least $75 billion in daily repurchase agreements through Nov. 4 to ensure continued liquidity.

- On Oct. 8, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell outlined a plan to boost the level of bank reserves in the system and confirmed that the Fed will continue repurchase agreement operations. Full details on the future of this program remain unclear, though Powell did note that these measures do not amount to full quantitative easing.

- On Oct. 30, following the FOMC meeting, Powell stated that the Fed is committed to keeping reserves at appropriate levels by continuing to purchase Treasury bills (T-Bills) through mid-2020 and maintaining current temporary market operations through January. In addition, the Fed plans to explore other methods such as improving intraday liquidity within the banking system.

Root causes of the repo spike

1. Post-GFC regulation has made banks more risk averse

It’s hard to argue that financial regulations stemming from the GFC haven’t materially strengthened the balance sheets of big U.S. banks. Today, banks hold more liquid assets, are better capitalized and have tighter underwriting standards compared to pre-GFC. In addition, banks are subjected to increased regulations involving risk management standards and stress testing against severe economic conditions.

Banking regulations have created unintended consequences by disincentivizing banks from participating in lending activity that could negatively impact their capital and liquidity ratios. Instead, banks have been incented to passively hold cash rather than engage in repo agreements—which require a market transaction with an outside counterparty and are thus considered riskier from a regulatory perspective. As a result, the size of the overnight general collateral repo market (Treasury and Agency) has declined more than 70% in wake of GFC regulatory reforms, and overnight liquidity has suffered.1

More stringent capital and liquidity requirements have also pressured banks to hold their safest assets (U.S. Treasuries) from a risk-based capital perspective, rather than lend them in the repo market. Some banks have expressed concern that year-end funding pressures are likely to worsen given the current dynamics.

2. Reserve balances were lower than normal

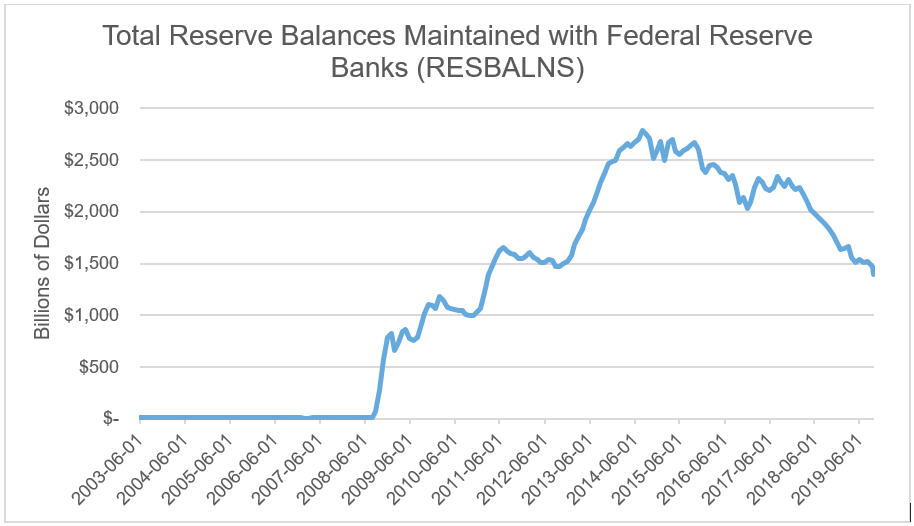

Banking system reserves peaked at $2.8 trillion in August 2014 when the Fed ended its quantitative easing program. Over the past five years, the Fed had attempted to gradually shrink the system’s reserves to a more normalized level.

Click image to enlarge

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.)

The minimum level of reserves that banks must hold for regulatory requirements is estimated to be approximately $1.2-$1.3 trillion. Based on data from the Fed, total reserve balances have been edging closer to these levels. This was one factor that led some dealers, over the summer, to predict a potential disruption in the repo market.

3. Tax payments and U.S. Treasury settlements

Quarterly corporate tax payments (estimated at more than $100 billion) and a significant increase in net Treasury issuance at the monthly auction (over $50 billion of T-Note settlements, offset in part by net T-Bill maturities) were another principal drain on system reserves. A combination of these factors created a cash shortage at a time when the system required more liquidity to meet institutional demand.

4. The repo market disruption is another example of the increasingly common market glitch

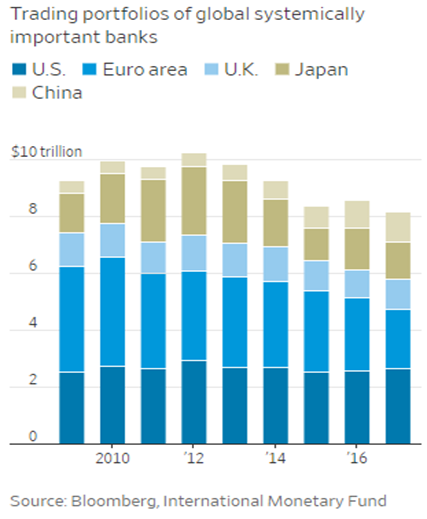

Trading portfolios of systemically important global banks have experienced a significant decline since 2012. As banks pull back from trading, markets have experienced a number of unusual trading events (like flash crashes) as other market participants (hedge funds, algorithmic traders and others) step in to fill the liquidity void.

In the past, banks were better positioned to act as significant market participants—providing the liquidity necessary to moderate extreme price changes during volatile markets. The current environment has produced a situation where banks are fundamentally stronger but less incentivized to take risk. They now lack the incentives and infrastructure necessary to provide liquidity and support the increased trading activity needed to ensure orderly markets during periods of market stress. The result is that markets are more susceptible to short-term dislocations than in years past.

Conclusion

Several factors converged to cause disruption in the repo market last month. The bottom line is that the system held inadequate reserves, which led to a lack of liquidity in the overnight financing markets. While the Fed is acting to implement longer-term solutions to provide more liquidity on an as-needed basis, their estimation process seems to have misjudged the level of reserves.

The repo event also illustrates structural changes driven by post-GFC regulation that have altered bank incentives. This factor, combined with the actions of market participants who have filled the void left by banks, will likely continue to affect various markets in unpredictable ways. However, while important settlement dates (like tax payments and U.S. Treasury auctions) and capital ratio measurement dates (like year-end and quarter-end) will drain liquidity in the system again going forward, we believe the Fed’s shift to a larger balance sheet and its temporary funding operations signifies increased vigilance and their commitment to avoid another major bout of repo funding stress.

1 Source: www.newyorkfed.org