Will inflation accelerate this year?

Inflation can be like molasses.

It often moves slowly—until it doesn’t.1

Overall, inflation tends to be a heavily lagging economic indicator, with upward price pressures typically not being realized until an economy has already reached the overheating stage. For instance, a country’s labor market may be stretched beyond capacity, while at the same time, prices are only modestly budging upward.

2019, anyone?

It’s no secret that one of the principal reasons the U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed) shelved plans for rate increases through at least the first three quarters of this year is sluggish inflation—which, by one common measure, likely remains below the central bank’s 2% target. It’s also no secret that the U.S. unemployment rate continues to hover near an all-time low for the current economic cycle.2

Does this mean that inflation could spike without warning sometime later this year? What about in 2020?

Our answer: An acceleration appears unlikely through the end of this year, but all bets are off for 2020. To understand why, let’s take a step back and look at three common causes of inflation.

Three drivers of inflation

Inflation is typically driven by:

- Anticipation

- Demand-pull

- Cost-push

Anticipation is the market’s expectation of future inflation. Anticipation can contain information from recent trends, as well as any forward-looking information. Often, there’s an element of self-fulfilling prophecy at play here. Why? Suppose in the aggregate, individuals make business decisions based on an expectation of 2% inflation. Then, surprise, surprise, we’ll end up with 2% inflation.

Demand-pull comes from an increased aggregate demand for goods. This uptick in demand often happens during times of low unemployment or high wages, since strong consumer fundamentals often leads to increased spending. This can also take place when a government or central bank injects monetary or fiscal stimulus into the economy.

Cost-push is driven by higher production costs, which producers pass on to consumers in the form of steeper prices. Production costs can rise due to an increase in taxes and tariffs, higher per-unit labor costs, an uptick in raw materials prices (such as oil) or weakening exchange rates.

The current strength of the U.S. dollar, for instance, is one of the factors that has kept inflation down over the last several months. When the currency is strong, it takes less dollars to purchase foreign imports, which puts downward pressure on prices. However, we expect the purchasing power of the dollar to erode by late this year, lowering the exchange rate and leading to a potential uptick in inflation.

Two of the three inflation drivers are here. But anticipation isn’t.

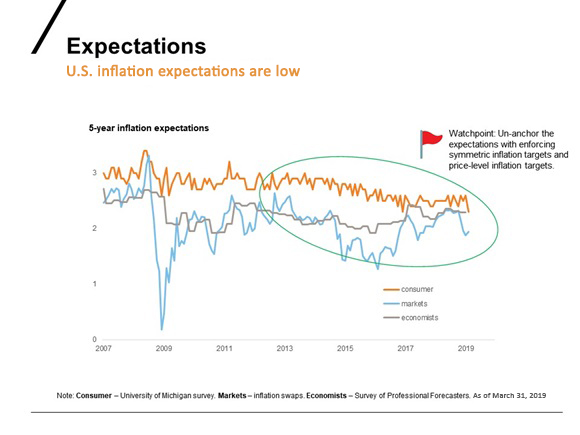

Recent data indicates that the demand and cost pressures that drive inflation are present in today’s economy. However, empirical evidence suggests that anticipation is the primary predictor of inflation3. With this in mind, take a look at the chart below, which shows five-year inflation expectations among consumers, markets and economists.

Note that across all three measures, expectations are currently hovering near the bottom of recent ranges. This supports the case for stable inflation moving forward. Because inflation expectations are anchored at such low levels, we believe that inflation through the end of the year is likely to remain stable.

However, the same may not ring true next year. We do see the potential for a rise in inflation come 2020—mainly due to the lack of spare capacity within the U.S. economy.

Spare capacity: The catalyst for inflation acceleration?

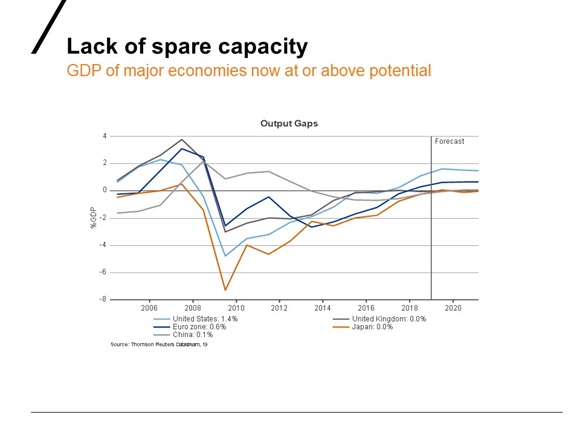

As the chart below shows, the GDP (gross domestic product) of all major economies is currently at or above potential. This includes the U.S., the UK, China, Japan and the eurozone.

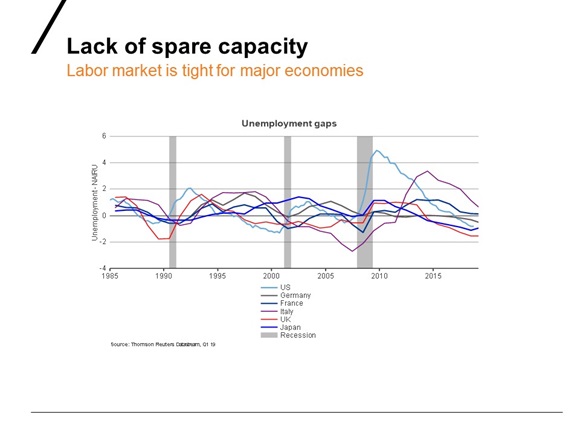

In addition, labor markets are tight worldwide. The chart below illustrates the lack of spare capacity in the aforementioned major economies.

So, what’s the consequence of all this? Rising wages across the globe. This is important because, in general, higher wages are often supportive of a consumer who wants to spend. In the aggregate, this could create upward pressure on prices.

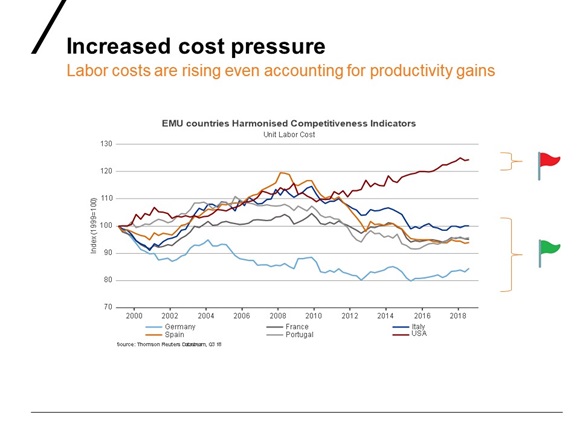

There are also cost implications to a tight labor market—chief among them an increase in cost pressure for producers. The chart below shows the per-unit labor costs for several major European countries, as well as the U.S.

Across the eurozone, per-unit labor costs are still relatively low, which is supportive of stable inflation. However, as the graph demonstrates, this isn’t the case in the U.S, where labor costs appear to be rising—even accounting for productivity gains. If U.S. producers pass this increase in labor costs on to consumers via higher prices, inflation could accelerate.

What else could potentially give inflation a boost?

Inflation has also been hampered by a slew of transitory headwinds, which we believe will become tailwinds in the future. The first of these is the global bias toward monetary tightening among central banks that existed prior to January 2019. After the Fed signaled a pause in interest-rate hikes on Jan. 30, pivoting to a more dovish stance, many other central banks followed suit. This shift in dovishness is stimulatory, and could support higher inflation down the road.

The second headwind has been the strength of the U.S. dollar. The dollar’s bull run has lowered import prices in the U.S., but we expect the dollar to weaken or stabilize later this year. Once this happens, inflation could rise faster.

The third headwind has been cheap oil. The low cost of oil, particularly late last year, may have led to softer inflation in recent months. However, going forward, we expect oil to rebound higher, supporting higher price inflation.

Taken together, these three transitory factors may help explain why inflation remains soft despite a lack of spare capacity and high wages.

Bottom line: Inflation should remain stable as long as anticipation remains low

Ultimately, we believe that inflation will remain relatively stable through the end of 2019, before possibly rising at a faster clip in 2020. Anticipation, in our view, trumps all other factors as the central driver of inflation—and anticipation remains low. Until forward-looking expectations begin to rise, inflation is likely to plod along at a snail’s pace.

Just like molasses.

1 Recall the infamous Great Molasses Flood of 1919 in Boston, Massachusetts. A burst molasses tank sent millions of gallons of molasses through the streets, causing mayhem and destruction. Slow until it’s not, indeed. Source: https://www.history.com/news/great-molasses-flood-science