Battling market uncertainty: Is the best offense a good defense?

Whoever said that the best defense is a good offense probably wasn’t thinking about financial markets.

At least not in the latter stages of the market cycle.

As we head deeper into the final quarter of 2019, global markets remain at a crossroads on what the future holds, with a strong U.S. consumer and labor market pitted against a contracting manufacturing sector and sagging business confidence. While it’s often said that uncertainty is the perpetual travelling companion of markets, this year really has been something else. Market volatility has come in waves, with stomach-churning drops on the backs of dismal manufacturing and trade news, and equally significant rises following upbeat headlines on U.S. employment and consumer spending.

Amid all this uncertainty, the exact opposite of the aforementioned saying appears more appropriate. In other words, we believe that the best offense for outcome-focused investors today is to adopt more of a defensive stance.

Why? In order to fully explain, it’s helpful to zoom out a bit first and take a look at why markets find themselves in limbo today.

Glass half-full: Solid growth, strong labor market

Uncertainty doesn’t necessarily mean bad, as the U.S. economy has demonstrated all too well this year. Despite sizable global headwinds, America has charted solid—if not spectacular—growth in 2019. The 3.2% GDP (gross domestic product) growth rate logged during Q1 was surprisingly strong, while Q2’s 2.0% pace beat consensus expectations.1 Q3 followed suit, with the economy growing at a 1.9% clip on an annualized basis.

Job creation has also been remarkable in the face of increasing uncertainty, with the U.S. economy adding 160,000 new jobs per month—well above the replacement rate (the estimated number of additional jobs needed each month to keep pace with population growth) of 100,000. Unemployment, too, is stellar—at 3.6%, it remains near a 50-year low.2 Finally, interest rates are historically low, the housing market has shown resilience and wage growth and consumer spending continue to power the economy.

Glass half-empty: Slipping CEO confidence, manufacturing downturn

Yet for every glass-half-full take on the economy, there’s a glass-half-empty counterpoint to be made. Take, for instance, CEO confidence levels. After already registering back-to-back negative readings of 43 in the first and second quarters this year (per the Conference Board, a reading below 50 indicates a prevailing negative outlook), the organization’s measure of CEO confidence plunged to 34 in the third quarter—the lowest level since the first quarter of 2009.3 That, of course, was when the U.S. was mired in the depths of the Great Recession.

Consumer confidence, while still elevated, has also recently weakened. In September, the Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index fell nine points, after a much smaller decline in August. Consumer confidence continued to wane during October, with the index edging down to 125.9—its lowest level since June.4 While it remains to be seen if this is the beginning of a long-term decline or just a temporary setback, the drop is noteworthy, as the U.S. consumer is the country’s bulwark against a recession. Further adding to the concern is September’s U.S. retail sales report, which showed a 0.3% drop in household spending4—the first time in seven months retail sales have contracted. Remember, consumer spending accounts for roughly two-thirds of the U.S. economy.

Perhaps the greatest warning sign to the health of the economy comes from the manufacturing sector, which has been deteriorating on a global scale since May.6 The U.S. no longer appears immune from this worldwide slowdown, with the American manufacturing sector contracting for the third consecutive month in October, per data from the Institute for Supply Management (ISM). Notably, the ISM’s October reading came in below consensus expectations again, as trade uncertainty continues to weigh on the industry. Even the much larger U.S. services sector, while still in expansionary territory, is weakening—currently growing at the slowest pace in over three years.7

Markets over the past year: The road to nowhere

So there you have it: The good, the bad and the ugly. These conflicting signals on the state of the American economy offer reasons for investors to be both confident and fearful. This is exactly why markets have been teeter-tottering for much of 2019—up one month, down the next, then back up and, whoosh, down again. The basic question they’ve been struggling with is the one that’s perplexing us all: Will the U.S. economy—and by extension, the global economy—fall into a recession in the next 12 months or not?

Unsurprisingly, the market has yet to make up its mind. Case-in-point: The S&P 500® Index closed at 2,901 on Sept. 30, 2018. Fast forward one year later, and it stood at 2,976.8 In other words, over the course of a year, markets have effectively gone nowhere.

Yet, recall that this road to nowhere has been quite the wild ride for equities, punctuated by a 19.8% downdraft in the fourth quarter of last year. The bond market, on the other hand, has basically moved in one direction all along. Over the course of the past year, yields have consistently fallen, with the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield going from 3.15% on Oct. 31, 2018, to 1.69%, as of Oct. 31, 2019. Simply put, bond yields do not fall when the bond market is confident in economic growth.

2020 recession: yea or nay? Let’s reframe the question.

So, will there be a recession in the next year? It’s the million-dollar question to which there is no million-dollar answer. Truth be told, the only answer any individual can give with high confidence right now is neither yes or no, but who knows?

While very honest, that’s also not a very helpful answer. So, let’s reframe the question: Given all the conflicting signals on whether or not the U.S. could experience a recession within the next 12 months, what steps should investors consider taking?

First things first: Above all else, stick with your investment plan. Remember, your plan was built specifically with this level of uncertainty in mind. Uncertainty is a fact of life for markets. Markets wax and wane, just as the sun rises and sets. Your plan was likely designed with the expectation that a recession would occur somewhere along the way—meaning that it was constructed specifically to weather a market downturn.

Next, on the margin, consider being more defensively positioned than offensively positioned. Remember, the U.S. is in the 11th year of both the bull market and the economic expansion—and we all know that the good times can’t last forever.

Playing defense

At Russell Investments, we’ve adopted a more defensively-oriented strategy this year by trying to avoid the most expensive parts of the market, such as the tech sector. Why? It all boils down to the basic notion of buying low and selling high. As the bull market and expansion slip further into old age, it becomes harder to see the wisdom of buying securities at historically high levels on the assumption that today’s highs could become tomorrow’s lows. It’s not 2013 anymore. We firmly believe that the explosive growth witnessed earlier this decade is in the rear-view mirror for this cycle.

It’s also important to bear in mind that how far you fall strongly depends on how high you are when the initial tumble beings. As Dr. David Kelly of J.P.Morgan Asset Management said recently, it’s hard to get hurt jumping out of a basement window. Taking a defensive stance may not be glamorous, but it’s likely to spare you a lot of pain down the road.

Tactical views

U.S. underweight

We retain an underweight in expensive markets, styles and factors. Our biggest market underweight is the U.S. Why? Consider this: Over the last 10 years, the S&P 500 has outperformed all other equity markets across the globe by 7.76%, per the MSCI World ex-USA Index.

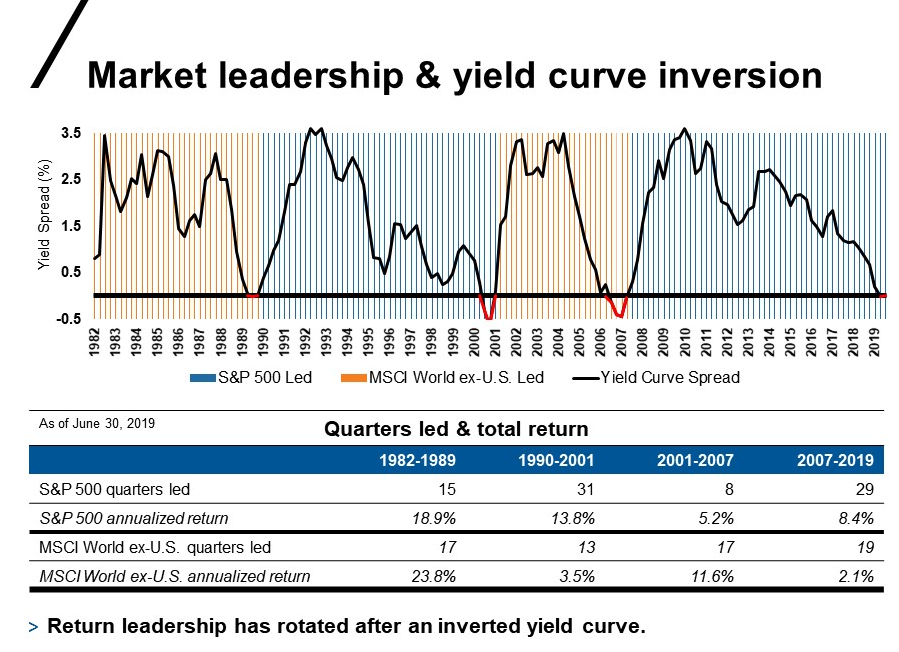

As we know all too well with markets, what comes up must come down. Take a look at the chart below, which shows how market leadership has rotated in and out of the U.S. since the 1980s. Notably, each inversion of the U.S. Treasury yield curve has led to a change in market leadership. Like I said earlier, the good times for the U.S. won’t last forever.

Click image to enlarge

Value overweight

From a style perspective, we are underweight growth and overweight value. Why? Again, it goes back to the idea that, in a downturn, the higher you are, the further you have to fall. It’s no secret how expensive growth stocks—think big tech—are today. Consider that over the past 10 years, the Russell 3000 Growth Index has outperformed the Russell 3000 Value Index by a cumulative 132.86% (as of Sept. 30, 2019). This, in our view, makes growth stocks all the more susceptible to steeper price drops when the next downturn hits and corporations are forced to slash capital expenditures and cut back on hiring.

The bottom line

When uncertainty is high, so too should be the bar for risk-taking. Avoiding the most expensive parts of the market is not only a prudent way to mitigate risks in today’s uncertain market environment, but it also aligns well with our core investment belief of buying low and selling high. This approach—detailed in the first major investment book written by industry icons Benjamin Graham and David Dodd—is a time-proven strategy, demonstrated all too well by the life’s work of their most famous disciple, Warren Buffet.

Ultimately, in a world where no one knows what comes next, adhering to this core principle may be the strongest defense against the next market downturn.

1 Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/gdp-growth

2 Source: https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000

3 Source: https://www.conference-board.org/topics/CEO-Confidence

4 Source: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/10/29/us-consumer-confidence-for-october-comes-in-at-125point9-vs-128-expected.html

5 Source: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/10/16/us-retail-sales-september-2019.html

6 Source: https://www.pmi.spglobal.com/Public/Home/PressRelease/6d5ffb41584d4c08a54706d85d3580b3

7 Source: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/10/03/september-ism-non-manufacturing-index-at-52point6-vs-55point3-est.html

8 As of Sept. 30, 2019.