The Reserve Bank of Australia’s 2018 New Year Resolution: Correct the policy mistake of 2016!

When considering the RBA’s actions, it’s important to consider the market conditions back in 2016. 2016 saw the Australian economy facing two quite different dynamics. On the one hand, the RBA was concerned about the buoyant property market and the associated risks with rising household debt. On the other, both the domestic and global economies were facing potential uncertainties and tail risks. Against this backdrop, the RBA signalled a bias to leave cash rates unchanged while allowing macro-prudential measures to bear the brunt of efforts to curb bank lending to the property and household sectors. Unfortunately, the vagaries of the economy intervened with several materially lower-than-expected inflation readings putting increased pressure on the RBA to respond. Faced at the time with what appeared to be (a) a slowing domestic residential property market and (b) heightened tail risks associated with the global economy, the lower-than-expected inflation outcomes left the RBA with few reasons not to implement further rate cuts as insurance against low inflation.

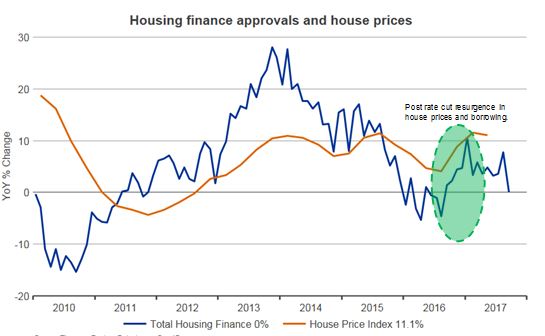

Perversely though, in taking out its insurance and trying to spur higher inflation, the RBA may have aggravated the other dynamics they were hoping would moderate, including a buoyant property market and the subsequent risks associated with higher levels of household debt. Indeed, as Figure 1 below highlights, the timing and magnitude of these rate cuts are likely to have contributed to a further increase in house prices and household indebtedness in the second half of 2016.

Figure 1: The Post Rate Cut Resurgence in House Prices/Borrowing

Pushing the 2016 rate cuts into the realm of policy mistakes are the very macro-prudential measures referred to earlier. The irony is that the RBA had been working closely with other regulatory bodies who in early 2015 introduced tighter macro-prudential requirements for bank lending on residential property. While such macro-prudential requirements were aimed primarily at maintaining the stability of the financial system, there seems little doubt that they were also introduced to curb what was seen by the RBA as “excesses” within the residential housing and loan markets. As the passage of time would demonstrate, at the time these macro prudential measures appeared to be taking the steam out of the residential property and loan markets the RBA rate cuts contributed to a reinvigoration of those same markets.

Potentially exacerbating the situation is that, in emphasising lower inflation to legitimise the 2016 rate cuts, the RBA may also have unintentionally created, in the public’s mind at least, a materially higher hurdle to justifying rate rises going forward than actually exists. More specifically, having cut interest rates due to lower than expected inflation outcomes, the RBA doesn’t necessarily need materially higher inflation to justify raising interest rates. Whilst there is certainly no denying a link between monetary policy and inflation, it’s arguably unwise to promote the literal interpretation of a close linkage. There are several reasons for this.

First, the RBA has a range of objectives which it’s trying to balance when setting cash rates, of which inflation is just one. Second, central banks in a number of developed countries have discovered from experience that the link between monetary policy and inflation is much weaker than previously anticipated, i.e. it’s quite difficult to use low interest rates to create inflation. As a result, central banks are increasingly sceptical that keeping cash rates overly accommodative is a desirable policy given (a) the recent failure of low interest rates to actually create higher levels of inflation and (b) the potential for low cash rates over an extended period of time to create imbalances in other parts of the economy.

So, as we look ahead to 2018, it’s possible the RBA may still raise interest rates even if inflation remains low. One of the drivers behind higher rates in Australia may be that the RBA finds itself pressured to higher rates by the actions of other foreign central banks – particularly the US Federal Reserve – taking steps to reduce the level of their own accommodative monetary policies. But more importantly, the RBA may themselves view the rate cuts they made back in 2016 as a policy mistake that needs to be reversed now that the global economy is becoming more stable. If this is the case, we may yet see the RBA’ New Year’s resolution for 2018 be to take back those earlier rate cuts by pushing the official cash rate back up to around 2.0% by the end of next year.