In the face of 2021 tax-rate uncertainty, tax planning matters even more

Investors and planners desire clarity around tax rates to help make informed decisions around investment moves and related impacts to portfolios. Unfortunately, tax planning in the near term likely won’t be easy. As we head into January 2021, we will have more uncertainty. And while uncertainty may seem like the biggest obstacle to tax planning, it’s also the biggest reason to do it.

Why the uncertainty?

- Control of the U.S. Senate won’t be decided until after the Senate run-off in Georgia scheduled for Jan. 5, 2021. And based on last November, we know it may be days after Jan. 5 to have full clarity for the winners.

- If both Senate seats are won by Democratic candidates, that would give the U.S. Senate a 50/50 split with the tie-breaking vote going to Vice-President-elect Kamala Harris.

- If one or both open seats goes Republican, the U.S. Senate would remain a Republican majority.

Why does this matter? It is hard to envision major tax reform being passed without Democratic control of the Senate. With Republican control of the Senate, there may be minor tweaks to the tax code, but likely nothing major like proposed by President-elect Joe Biden during the campaign. And if the Democrats achieve the 50/50 split, this is not a guarantee they would support all of the items as proposed by then-candidate Biden.

This uncertainty is leading many investors to wonder if they should consider any changes to portfolios before year-end or in 2021 in anticipation of possible tax rate increases. There is a reason that tax code changes, such as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) passed in December of 2017, are so infrequent. It is hard to do! The prior tax code change of similar scope and size was the Tax Reform Act of 1986—more than 30 years ago.

While there is much discussion about what may or may not change, note that many parts of the individual tax code changes passed as part of the TCJA are set to sunset or expire after 2025.That means absent government action, most individual and estate tax rates will go back to prior levels that were in effect before the TCJA. To pass the TCJA, Congress agreed to make many of the individual tax changes temporary—10 years in duration. You may recall this same situation when the Bush-era tax cuts were set to expire in 2010 (10 years from passage in 2001).2026 may sound like a long way off, but it will be here in a blink of the eye. And it should be part of any tax-planning analysis.

Timing of possible changes

If the Biden administration is able to line up the votes, and prioritizes making individual tax code changes, the question is: When might the changes be effective? Would anything passed in 2021 apply to the taxes due for that year? Meaning: Would the tax code change apply retroactively to income earned in 2021 or would the changes apply to earnings for 2022 (due in April 2023)?

Based on prior tax changes and court rulings, there is nothing that precludes the legislation from being retroactive to the beginning of the year when passed. That means if a tax increase is passed in 2021, the new rates could apply to income earned that year. Given the challenges facing the economy, it’s hard to see the new administration being able to write, propose and pass material tax changes that quickly, but it is possible. Additionally, the longer the debate would go into 2021, it’s even harder to believe any passed legislation would be retroactive to the first of the year. But again, prior rulings don’t preclude this from happening.

Prior tax case law states:

“Retroactive taxation is allowed because taxation is neither a penalty imposed on the taxpayer nor a liability which the taxpayer assumes by contract, but rather a method of apportioning the cost of government among those who enjoy its benefits and who must bear the resulting burdens. In addition, some limited retroactivity may be necessary as a practical matter to prevent the revenue loss that would result if taxpayers, aware of a likely impending change in the law, were permitted to order their affairs to avoid the effect of change.” (Mertens Law of Federal Income Taxation §4.15, Retroactivity.)

In recent history, most of the tax changes implemented retroactively have been tax decreases—much easier to implement and to gain political acceptance.1It is possible the changes could be applied retroactively, but again, historically, that has not been the case.

What might change?

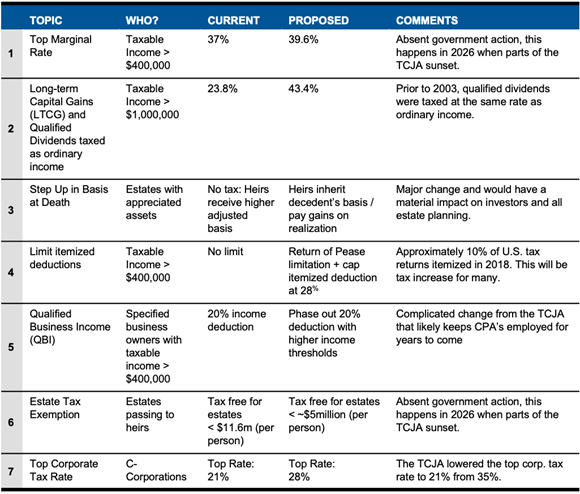

As I wrote previously, campaigning on tax proposals vs. passing them are two different things. Still, it’s worth revisiting the Biden tax plan for insight into where the administration may go for additional revenue. The table below is not an all-inclusive list—just a selection of those that are most likely to impact individual investors.

Click image to enlarge

For individual investors, items two and three could possibly have the biggest impact. Consider the impact of increasing the top tax rate on LTCG/Qualified Dividend from 23.8% to 43.4%. This 82% increase would materially change the hurdle rate for many projects. The attractiveness of certain projects would look vastly different from an after-tax perspective for investors and entrepreneurs (with taxable income > $1 million). For those taxpayers, this is big change.

Item #3 (elimination of the tax-free step up in basis at death) is an equal—if not more—material change. This strikes me as the type of change that was easy to propose but would be much more difficult to pass. It will for sure receive significant pushback from many, many investors and interested parties—regardless of political affiliation. The actual proposal did not have much detail in how it might be implemented, but either way, this is a material change for investors and those who plan to leave appreciated assets to heirs.

What to do in the face of uncertainty

We have all learned that nothing is for sure when it comes to political outcomes or trying to predict what happens several months out. There are no certainties. Investors should not get too speculative on what might happen. As in all forms of investing, it is best to focus on the probabilities—not the possibilities.

Good investments that fit as part of a long-term investment plan will still make sense. Recognize that campaigning on tax plans is much easier than actually passing them. Historically, tax decreases have often been retroactive, but tax increases less so. But again, it’s hard to say for sure. On passage of the U.S. Constitution, Ben Franklin is quoted as saying “. . . nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes”. While both are certain, the timing and how they might happen can be frustratingly hard to predict.

1 Source: https://www.natlawreview.com/article/capital-gains-rate-historical-perspectives-retroactive-changes